It is intriguing to imagine why, when in her sixties, Leonor Fini chose to illustrate texts about young girls – the perennial children’s classic Les petites filles modèles and the ‘symbolist bible’ Le livre de Monelle about the suffering and fortitude of young women having to fend for themselves in a dark world.

It is intriguing to imagine why, when in her sixties, Leonor Fini chose to illustrate texts about young girls – the perennial children’s classic Les petites filles modèles and the ‘symbolist bible’ Le livre de Monelle about the suffering and fortitude of young women having to fend for themselves in a dark world.

Sophie Rostopchine, Countess of Ségur’s Les petites filles modèles was a particularly interesting choice, as Leonor found plenty to identify with both in its author and in the story’s protagonists, young Camille and Madeleine. Sophie Rostopchine (1799–1874) grew up in a strict Russian aristocratic family where high educational standards (she could speak five languages when she was sixteen) came with regular punishments from both parents and teachers. Quite understandably she was a rebellious child, reading widely and choosing, against her father’s wishes, to convert from Russian Orthodoxy to Roman Catholicism at the age of thirteen.

During the 1812 invasion of Russia by Napoleon’s army Sophie’s father was governor of Moscow, and in 1818 he brought his family to Paris; it was there that Sophie met Eugène de Ségur (1798–1869), grandson of the French ambassador to Russia. The following year her parents returned to Russia. The marriage was not a happy one, though it did produce eight children. Eugène was a womaniser and was frequently absent from home, so Sophie concentrated on her children and grandchildren in the Château de Nouettes at Aube, west of Paris. It is highly likely that Eugène gave Sophie gonorrhoea as well as the eight babies, as she was diagnosed as hysterical, exhibiting nervous attacks and long periods of silence.

She started writing when she was fifty, and over the next twenty years produced two dozen volumes of stories and novels. She started telling her stories to her offspring at the château, but her career started in earnest when Eugène mentioned then to publisher Louis Hachette; the enterprising founder of the Hachette publishing empire. Sophie saw a creative opportunity, Eugène and Louis saw income. A book of fairy tales was published in 1856, and Les petites filles modèles, the first of a trilogy, came two years later.

The two main characters in Les petites filles modèles, Camille and Madeleine, are based on real children, Sophie’s granddaughters Camille and Madeleine de Malaret; as she writes in a short introduction, ‘Les petites filles modèles are not imaginary; they portraits of little girls who really exist. The proof of this is their very imperfections. They have faults, little shadows which highlight their charming characters and testify to those goals to which we all aspire. All who know the author will recognise that Camille and Madeleine are very real.’ Les petites filles modèles (Perfect Little Girls) is of course a title with much irony; Camille and Madeleine are far from perfect, and like all children have to learn the hard way the difference between right and wrong, the ‘wrong’ often the result of the best of intentions. Halfway through the book a third little girl appears, tellingly named Sophie, with a cruel mother-in-law who believes the whip to be the solution to all discipline issues.

Leonor Fini’s illustrations for Les petites filles modèles are a remarkable interpretation of how children actually look and behave; they are not always pretty and sweet, and Leonor’s little girls scowl, pout and frown very convincingly. They are also fascinated by each other’s bodies, just as real children are; the comparison of diminutive genitalia with the aid of a magnifying glass makes for a memorable image that many real girls, old and young, will readily identify with.

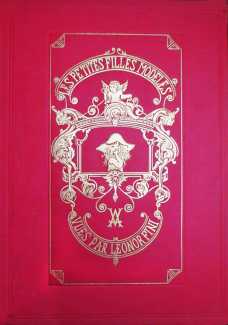

The Fini-illustrated portfolio of Les petites filles modèles was published by Arts et Valeurs, with twenty engravings created by Henri Renaud from Leonor Fini’s drawings. It was produced in a boxed numbered edition of 305 sets.

Les petites filles modèles has remained a French classic, with Hachette still selling more than ten thousand copies a year into the twenty-first century; it is therefore remarkable that no English translation appeared until 2010. Published by Simon & Schuster and titled Camille and Madeleine: A Tale of Two Perfect Little Girls, Stephanie Smee’s translation is excellent; the cute illustrations, however, lack any originality.