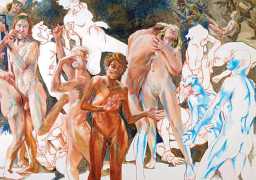

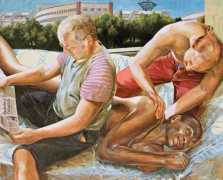

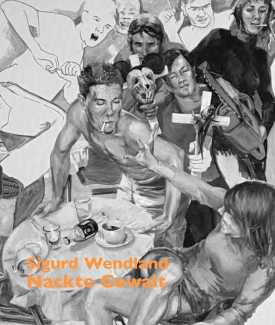

Nackte Gewalt (Naked Violence) is the title of a 2010 publication to accompany an exhibition of the same title in Berlin, but it can also stand as an overarching theme for much of Sigurd Wendland’s work from the 1990s onwards. As Wolfgang Schorlau writes in the introduction to Nackte Gewalt, ‘There is no doubt that Sigurd Wendland is a political painter. He is not an easy preacher, but is someone who clearly takes a position and shows real attitude. In doing so, he is taking a big risk in today's art world.’

Nackte Gewalt (Naked Violence) is the title of a 2010 publication to accompany an exhibition of the same title in Berlin, but it can also stand as an overarching theme for much of Sigurd Wendland’s work from the 1990s onwards. As Wolfgang Schorlau writes in the introduction to Nackte Gewalt, ‘There is no doubt that Sigurd Wendland is a political painter. He is not an easy preacher, but is someone who clearly takes a position and shows real attitude. In doing so, he is taking a big risk in today's art world.’

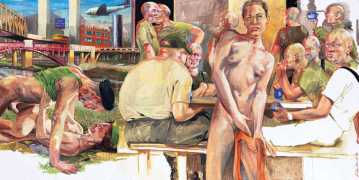

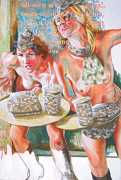

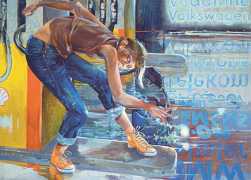

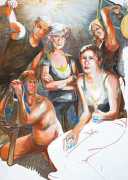

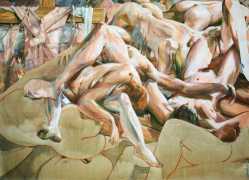

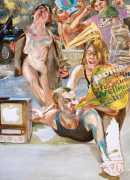

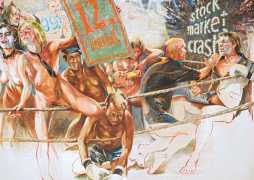

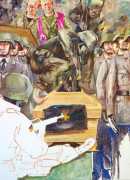

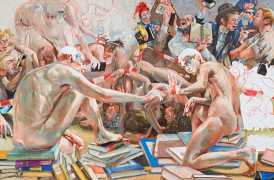

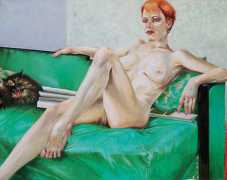

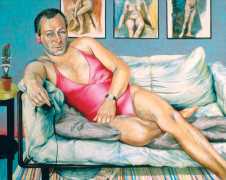

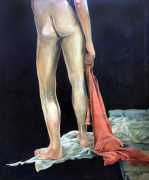

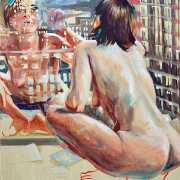

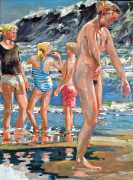

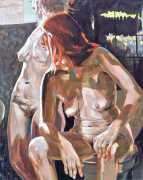

In his very distinctive paintings, Wendland provides an artistic commentary on many aspects of social, economic and political life in modern Germany. His large canvases reference well-known brand names and popular culture, as well as religion and politics, particularly the more militaristic aspects of post-Soviet Germany. Many include some degree of nudity, reminding the viewer that under the veneer of clothes and social conventions our naked bodies are always close to the surface.

Schorlau’s introduction continues, ‘What is amazing is that it's easy to see more than just the moment that's captured in Sigurd Wendland's pictures. I have no problem seeing the seconds before and after this moment. Some images even make me feel like I'm watching a short film. I check the pictures one by one, I feel the same way about almost all of them. There is no doubt about it: Sigurd Wendland creates not just a picture, but a scenario. The paintings are very often ensemble affairs. Rarely is a character alone, and the people depicted are nearly always moving. On closer inspection you even think you can recognise the motives of their actions. They have a life of their own, and I haven't been able to find any examples where they are just illustrations. It is precisely this fragmentary character of his images that challenges the viewer's attention; the juxtaposition of detail, precision and apparent fleetingness increases the tension, just as if a detective were tracing a murderer's every movement but not seeing his face.’

In November 2009 Ralf Landmesser conducted an extended interview with Sigurd Wendland, which you can read in full here (in German). We have extracted some of the more interesting questions and responses.

Have you always been good at painting?

It was clear to me from childhood that I wanted to be a painter, though my parents said you can’t make any money from it. My father said I should become a teacher or a commercial artist.

How did your painting develop thematically?

I started studying was during the era of the radical leftist Red Army Faction. This time shaped me politically. In the early to mid-1970s there was a real political crackdown, bars were suddenly sealed off and there were frequent police raids. It was experiences like this that made me what many call ‘a political painter’.

When did you interest in anarchism start?

It started with a copy of Kropotkin from the second-hand bookstore. I still have it today, it’s from 1910. Later I read Proudhon, and studied the Soviet Republic, Landauer, Mühsam and other anarchist classics. During my first studies, which was from 1969 to 1973, I studied philosophy with Leo Kofler, a Marxist social philosopher.

How much do you care whether people like your work?

Actually I don’t much care whether people like it or not. I’ll just paint. They have to live with it, and so do I. And since what I’m doing isn’t a commercial success, it could be that I’m on the wrong boat. There’s no other way for me; I couldn’t imagine doing anything else.

For your painting do you need more calm, or phases where you are more agitated?

Both. The way I do it is that I go to the studio in the morning and spend my hours there and say, I’m going home at this time; and sometimes I go back to the studio at night. A hard thing is that while I’m painting I usually already have ideas for the next picture. But if you give in to that, the first one will never be finished, so you have to finish that one before you move on to the next.

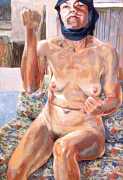

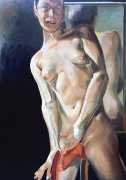

You have made many pictures that address sexuality in all its possible forms. How did you come to these forms of representation?

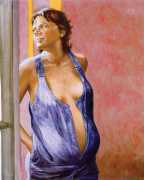

Artists have always painted nudes. In the middle ages they needed excuses, and sought out ancient or biblical stories where sexuality or naked bodies were allowed to be shown. Nudes themselves are more true, undisguised and not superficially fashionable.

But for you it’s less about the classic nude, and more about group scenes which include nudity.

That’s the narrative principle. I have a specific story in mind and try to represent it with my models. When I work with models, I consciously keep my distance from them, so no physical contact whatsoever and they know exactly what is happening. Like actors, they have to portray something for me. This is difficult because it is not supposed to be pleasurable. It’s using sexual imagery to tell particular political scenarios or stories.

Do you enjoy creating such paintings?

I paint what I enjoy. I like to paint people, and I also like to see them undressed. There are also only very specific types that I choose. It’s usually slightly older men or women who model for me. Younger people have so little lived life on their faces. Michael Rutschky once said about the beauty of women, ‘In order for women to be beautiful, the dying must have already begun. On a young, smooth body, your eyes slip out.’ But I have also worked with beautiful models.

What would you see as the task of libertarian art? Does such a thing even exist?

As an artist you must under no circumstances integrate yourself into one particular political group, not become someone’s mouthpiece, but rather process and reproduce your own thoughts and interpretations.