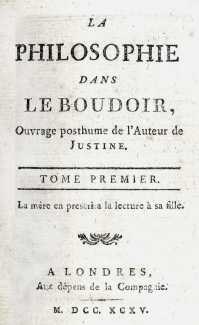

The first work by the Marquis de Sade with engravings attributed to Claude Bornet was La philosophie dans le boudoir (Philosophy in the Boudoir, or as some English translations have it less accurately, Philosophy in the Bedroom), published in 1795. On the title page the book is described as an ‘Ouvrage posthume de l’auteur de Justine’, a half-truth, because Sade was still very much alive, although he might have hoped that a printed claim that the author of Justine was dead would put an end to the persistent and well-founded rumours that he had written that infamous novel.

The first work by the Marquis de Sade with engravings attributed to Claude Bornet was La philosophie dans le boudoir (Philosophy in the Boudoir, or as some English translations have it less accurately, Philosophy in the Bedroom), published in 1795. On the title page the book is described as an ‘Ouvrage posthume de l’auteur de Justine’, a half-truth, because Sade was still very much alive, although he might have hoped that a printed claim that the author of Justine was dead would put an end to the persistent and well-founded rumours that he had written that infamous novel.

La philosophie is a closet drama consisting of seven dialogues, in which pornographic action alternates with philosophical dissertations, the latter reinforced by the anti-religious, anti-moral tract ‘Français, encore un effort si vous voulez être républicains’ (Yet another effort, Frenchmen, if you want to be republicans). Depending on one's opinion of Sade, the epigraph of La philosophie, ‘La mère en prescrira la lecture à sa fille’ (Mothers should require their daughters to read it), and the subtitle at the beginning of the first dialogue, ‘Dialogues destinés à l'éducation des jeunes demoiselles’ (Dialogues intended for the education of young ladies), can be read as anything from delightfully ironic to outrageously perverse.

In La philosophie, Sade traces the transformation of an innocent ingénue, Eugénie de Mistival, into a criminal libertine, at the hands of three immoral instructors – Dolmancé, a dedicated atheist and sodomite; Mme de Saint-Ange, an artful woman whose good reputation conceals her indulgence in vice; and her younger brother and lover, the well-endowed Chevalier de Mirvel. Later, Mme de Saint-Ange summons her gardener, Augustin, another lover, whose endowment is even more impressive, to join the group. Everyone is having a good time until the virtuous and devout Mme de Mistival arrives to take her daughter home. Dolmancé and his companions, including an enthusiastic Eugénie, then subject her to the sadistic treatment we expect from the Divine Marquis before sending her packing so they can retire for a good meal and sleep, all in the same bed.

The 1795 edition of La philosophie contains just the five engravings shown here. The frontispiece, not particularly erotic, is a mythological tableau that most scholars identify as the Judgment of Paris, depicting Paris, Venus, Mercury, Juno, and Minerva, with Cupid flying overhead. The other four illustrate scenes from Eugénie's practical training, from oral sex with Mme de Saint-Ange and Dolmancé in the third dialogue; to mutual masturbation with the Chevalier added to the party in the fourth dialogue; to full-fledged orgies, choreographed by Dolmancé, in which Augustin is also a participant, in the fifth dialogue.

As was often the case with pornographic and otherwise provocative books produced and distributed clandestinely in eighteenth-century France, the stated place of publication for La philosophie dans le boudoir is false; the work was printed in Paris, not London. The date on the title page contains a typographical error – it should be M.DCC.XCV instead of M.DCC.XCXV – and the last four dialogues are erroneously numbered as third through sixth rather than fourth through seventh.

We are very grateful to our Texan colleague Phyllis Eccleston for the research and images presented here.