Jean de La Fontaine (1621–95) was born in the Champagne region into a bourgeois family. There in 1647 he married an heiress, Marie Héricart, but they separated in 1658. From 1652 to 1671 he held office as an inspector of forests and waterways, an office inherited from his father. It was in Paris, however, that he made his most important contacts and spent his most productive years as a writer. An outstanding feature of his existence was his ability to attract the good will of patrons prepared to relieve him of the responsibility of providing for his livelihood. In 1657 he became one of the protégés of Nicolas Fouquet, the wealthy superintendent of finance. From 1664 to 1672 he served as gentleman-in-waiting to the dowager duchess of Orléans in Luxembourg. For twenty years, from 1673, he was a member of the household of Madame de La Sablière, whose salon was a celebrated meeting place of scholars, philosophers, and writers. In 1683 he was elected to the French Academy after some opposition by the king to his unconventional and irreligious character.

Jean de La Fontaine (1621–95) was born in the Champagne region into a bourgeois family. There in 1647 he married an heiress, Marie Héricart, but they separated in 1658. From 1652 to 1671 he held office as an inspector of forests and waterways, an office inherited from his father. It was in Paris, however, that he made his most important contacts and spent his most productive years as a writer. An outstanding feature of his existence was his ability to attract the good will of patrons prepared to relieve him of the responsibility of providing for his livelihood. In 1657 he became one of the protégés of Nicolas Fouquet, the wealthy superintendent of finance. From 1664 to 1672 he served as gentleman-in-waiting to the dowager duchess of Orléans in Luxembourg. For twenty years, from 1673, he was a member of the household of Madame de La Sablière, whose salon was a celebrated meeting place of scholars, philosophers, and writers. In 1683 he was elected to the French Academy after some opposition by the king to his unconventional and irreligious character.

La Fontaine is best known for his Fables (Fables) and Contes (Tales). Of the two extensive collections, the fables unquestionably represent the peak of La Fontaine’s achievement. The first six books, known as the premier recueil (first collection), were published in 1668, and were followed by five more books (the second recueil) in 1678–9 and a twelfth book in 1694. The narratives in the second collection show even greater technical skill than those in the first, and are longer, more reflective, and more personal. La Fontaine did not invent the basic material of his fables; he took it chiefly from the Aesopic tradition and, in the case of the second collection, from the East Asian.

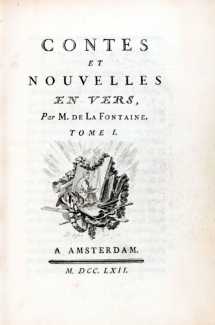

La Fontaine’s Contes et nouvelles en vers (Tales and Novels in Verse) considerably exceed the fables in bulk. The first of them was published in 1664, the last posthumously. He borrowed them mostly from Italian sources, in particular Giovanni Boccaccio, but he preserved none of the fourteenth-century poet’s rich sense of reality. The essence of nearly all his tales lies in their licentiousness, which is not presented with frank Rabelaisian verve but is transparently and flippantly disguised.

Unlike the Décaméron of five years earlier, all the plates for Fontaine’s Contes et nouvelles en vers were produced by Eisen, and in a bolder and more free-flowing style.

Although the two volumes state the place of publication as Amsterdam, they were in fact published by Barbou in Paris.