It is often best to let the artist speak for themself about their work and its significance. Here we have collated the most interesting questions and replies from two interviews with Nazanin Pouyandeh, by Siegfried Forster in 2017 and Daniel Lichterwaldt in 2020.

It is often best to let the artist speak for themself about their work and its significance. Here we have collated the most interesting questions and replies from two interviews with Nazanin Pouyandeh, by Siegfried Forster in 2017 and Daniel Lichterwaldt in 2020.

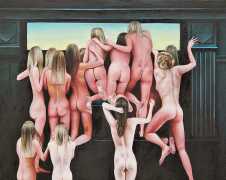

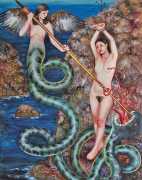

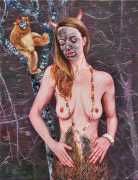

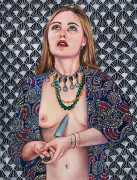

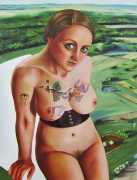

Your visual language is very recognisable and memorable – strong contrasts, lots of skin and untypical poses. How did that come about?

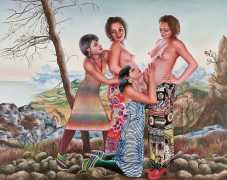

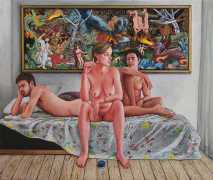

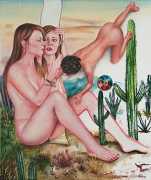

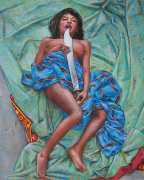

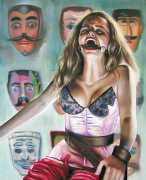

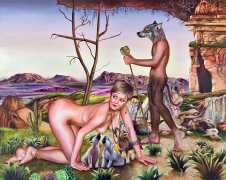

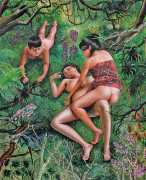

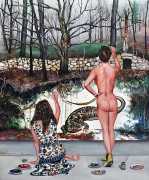

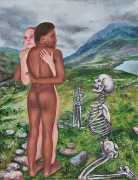

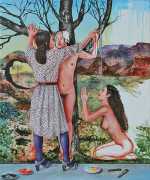

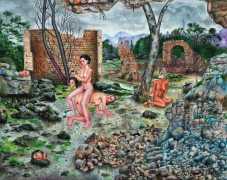

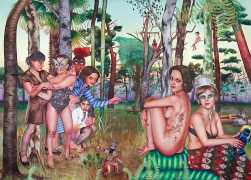

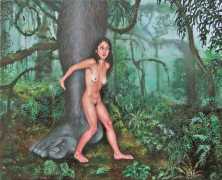

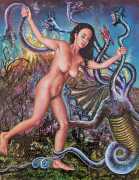

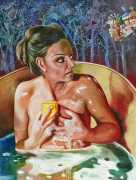

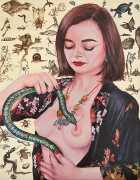

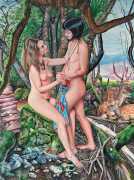

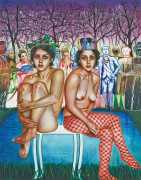

I think the origins of a visual language for a painter is rarely very conscious. As for me, it comes from how I see the world and what I want to express, but also from my utopias. In my paintings I deal with existential subjects such as desire, war, fear, love, death. I borrow from many different forms of expression, old paintings, cinema, the primitive arts. I always need a strong human presence in my paintings, so I also often ask my friends to pose for me and I take pictures of them to use as references.

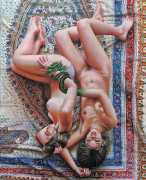

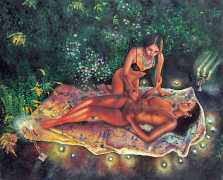

What does intimacy mean to you?

Privacy is often a secret, something of your own that you don’t expose. But artistic work has a direct link with intimacy. Art is a creative and poetic form of enhancing intimacy and showing it to an audience.

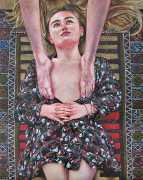

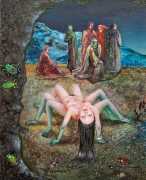

In one very colourful and semi-autobiographical drawing, you show a standing woman, made up of two halves, one half shows your body, the other half is populated by many scenes from human history. Is this sort of split a key element in understanding your work?

We are all double characters, both in the physical sense – we have an exterior and an interior –- but also in the psychic sense – what we show and what we do not show. It’s something that I think about a lot, it fascinates me.

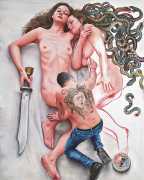

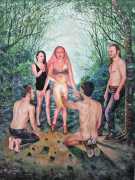

If we follow your logic, are you maybe trying to hide something very simple from us through the profusion of detail?

I don't paint to hide things. I express myself to show things. My goal is not to create a kind of hide-and-seek with the viewer. The mystery, if it is there, comes from the work itself and the viewer’s interaction with it, not from the multitude of details.

For those who know your history, the assassination of your father in 1998 and your departure for France shortly after are inseparable from your powerful and enigmatic work.

But I am not just the death of my father and my exile in the west. You cannot reduce a work to a particular event, be it tragic or wonderful. Art goes beyond that.

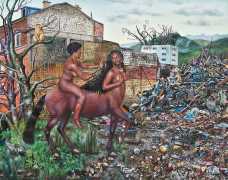

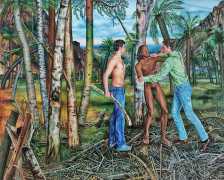

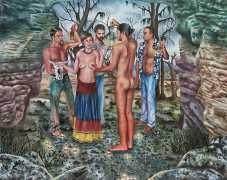

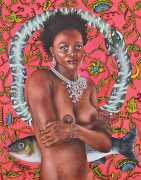

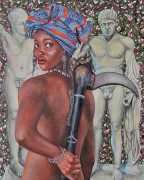

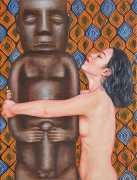

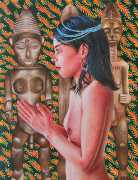

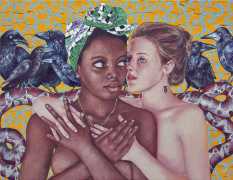

In 2017 you were invited to travel in Benin in west Africa, and to be part of the Ex Africa exhibition at the Quai Branly museum in Paris. How was that experience for you?

My trip to Benin was a very important step in my artistic creation. It nourished me enormously both on a human and on an artistic level. I felt I was able to connect with the people, and also with the art of Benin.