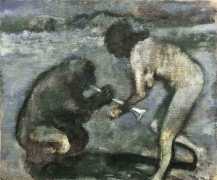

Savage Gardens is the title of an exhibition of paintings and drawings exhibited in London and New York, demonstrating the range and imagination of Lisa Ivory’s work. The paintings, with titles including Hairy Love, Hot Mess, Wanton and Brute, depict no-holds-barred encounters between woman and beast, in which both appear to be revelling in their naked savagery.

Savage Gardens is the title of an exhibition of paintings and drawings exhibited in London and New York, demonstrating the range and imagination of Lisa Ivory’s work. The paintings, with titles including Hairy Love, Hot Mess, Wanton and Brute, depict no-holds-barred encounters between woman and beast, in which both appear to be revelling in their naked savagery.

We can do no better than share art critic Richard Davis’s 2020 overview of her recent work.

In the shadowy recesses of the mind, in those spaces occupied by the strange peripheral visions that pour in through the corner of our eye, we find the monsters of our imagination. They are the creatures we cower from as children hiding under the bed, or imagine lurking in the undergrowth when we walk through a dark forest. They fill the pages of fairy tales, and they are there in the margins of medieval manuscripts, hidden beneath seats or concealed within the stone leaves of capitals and cathedral choir screens; a fantastical bestiary of hybrid creatures, half human – half beast, which both transfix and terrify. They are symbols of otherness, not only portraying the fearful thing out there, but our own otherness, our fear of the wild hairy beast hiding within.

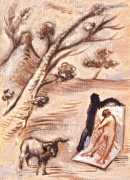

In our post-enlightenment age, most have become sceptical of the medieval bestiary, relegating its hybrid creatures to the toybox of childhood. Lisa Ivory, however, is an artist who navigates these shadowlands of the imagination, mining them for inspiration. She invites us to become innocent voyeurs; to tiptoe through crepuscular layers of scumbled oil paint to glimpse the moment when a Rubenesque naked beauty tames the beast. Normally shadows are places of terror where our imagination constructs fearful monsters to populate our nightmares, but in Ivory’s shadowy layers the hard edges dissolve, allowing a sense of gentle mystery to emerge. Unlike the woods of Ivory’s East London childhood, tainted and made ugly by human detritus, these spaces are suffused with the innocent wonder of a child who has not yet learnt to fear the natural world.

Ivory doesn’t offer us images of titillation or torment but of innocent interconnectedness. Her wild men are placid recipients of their companion’s attention. They stand quietly while their hair is stroked; they hold, cuddle and caress them as they are led with gentle chains. There is something mythic and allegorical in these intimate pastoral scenes, with the ‘other’ becoming a source of fascination rather than fear. The animal within has not been tamed and beaten into submission, but accepted and allowed to emerge.

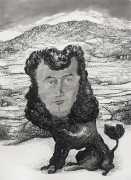

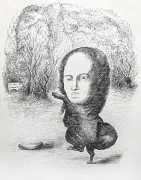

We find this emergence powerfully portrayed in Ivory’s work, which unites human and beast in strange hybrid forms that evoke the eighteenth-century caricatures of Rowlandson or Gilray. While the paintings explore a deeply intimate encounter between women and wild men, the drawings focus on the hybrid form of the beast/man. Yet the beast within these quiffed teddy boys and bearded and moustached nineteenth century mugshots is not a terrifying monster but a toy poodle, with a mane of carefully groomed hair. The only terrifying thing about this neatly coiffed lapdog is the prominent member between its back legs, but even then it frequently lies flaccid, deflated and tamed, unable to perform.

In Ivory’s paintings and drawings monsters dissolve into formless shadows and the other is tamed with silken chains. Even when they should shock, Ivory is able to seduce us with her exquisite mastery of paint and the confidence of her playful line. She tempts us to linger, and in doing so we discover the beauty within the beast.