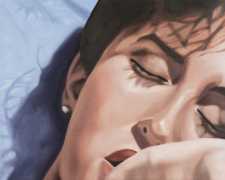

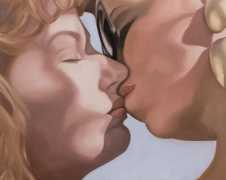

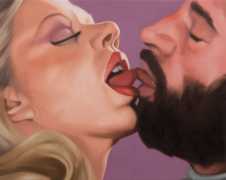

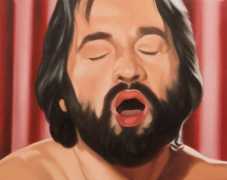

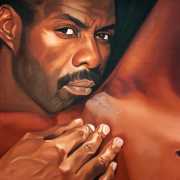

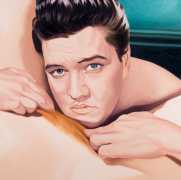

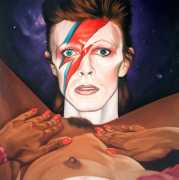

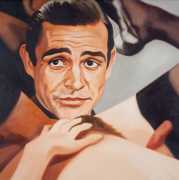

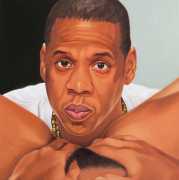

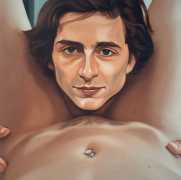

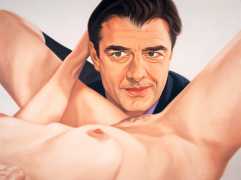

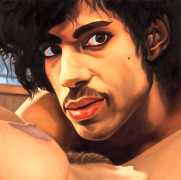

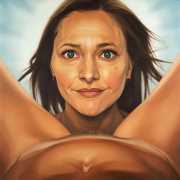

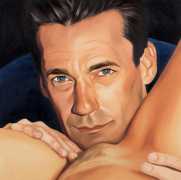

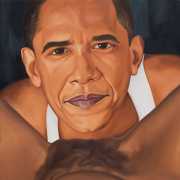

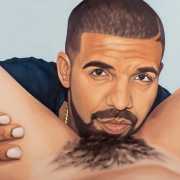

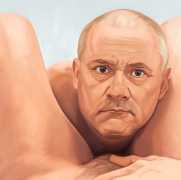

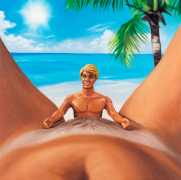

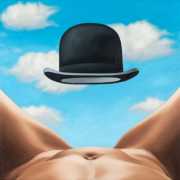

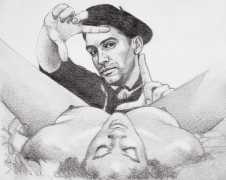

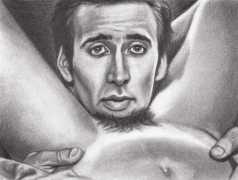

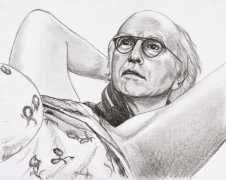

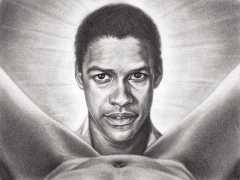

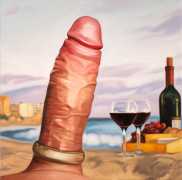

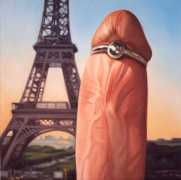

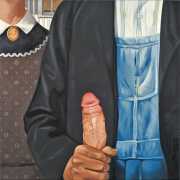

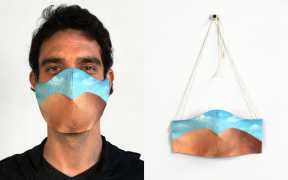

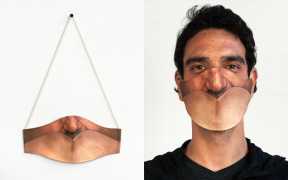

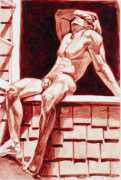

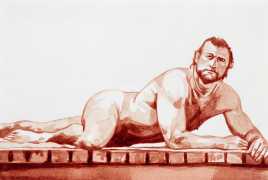

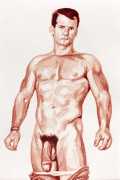

Alexandra Rubinstein’s witty and outspoken take on sexuality and patriarchy has earned her a well-deserved reputation as one of the foremost feminist artists of her generation. Her painting of Barack Obama apparently expertly performing cunnilingus earned her both praise and backlash, but it definitely put her on the artistic and cultural map.

Alexandra Rubinstein’s witty and outspoken take on sexuality and patriarchy has earned her a well-deserved reputation as one of the foremost feminist artists of her generation. Her painting of Barack Obama apparently expertly performing cunnilingus earned her both praise and backlash, but it definitely put her on the artistic and cultural map.

Rubinstein grew up in Sverdlovsk in the USSR, now renamed Yekaterinburg, Russia. Her mother is Russian and her father Jewish. They emigrated to the United States in 1997 and settled in Pittsburgh. Rubinstein showed an interest in art when she was in high school, attending classes at Carnegie Mellon University, where she earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree. After graduating, she moved to New York City to pursue a career in art. She currently works out of a studio in Brooklyn.

As she writes on her website, ‘Through education, therapy and self-help books, I’ve worked to identify my feelings and channel my rage and resentment into my work, through which I challenge outdated social systems and prejudices, and reconstruct the cis-heterosexual female experience by transforming women from passive objects to active consumers, taking back power and control without taking centuries of oppression too seriously. When I’m not working, I can be found running around Prospect Park, reading in the park, drinking wine at a bar near the park, and basically not leaving the neighbourhood. I’m still in therapy, and it’s going okay.’

Alexandra Rubinstein was interviewed recently by The House of Theodora online magazine; here is some of that interview, which can be found in full here.

How did you begin your journey as an artist?

I’ve been taking various art classes since I was about seven years old. I really honed in on it while I was in high school and in need of extracurriculars for my college applications. At the time, it was my only interest outside of boys, dieting, and binge drinking. I therefore applied mostly to art schools and to Carnegie Mellon University. While it wasn’t initially my first choice, CMU ended up being the most financially and logistically sound option, and came with a real college campus – an assimilation dream for any immigrant. I ended up loving CMU and really benefited from the programme, which focused on conceptual development and new media, broadening my approach to art making. It also introduced me to mentors who saw my artistic potential and provided encouragement, and frat parties that enriched my understanding of rape culture – I mean American culture. It was in that environment that I really began finding my voice and my vision, which I would take with me when I moved to New York after graduating.

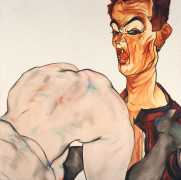

What words describe the style of your art?

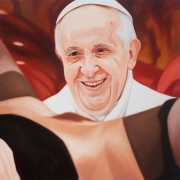

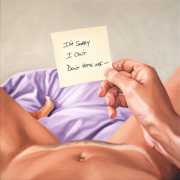

I primarily view my work as conceptual and playful. I spend a lot of time painting and on other technical aspects. I want the images to be strong enough to grab the viewer off the bat, whether that’s through their quality, content, or humour. But for me, there needs to be more beyond the surface, and the deeper issues I’m addressing in my work are social and political.

You spent your first nine years growing up in Russia and then you moved to the US. What was that like for a little girl?

Pretty tough. When my family and I first arrived, we were optimistic and incredibly grateful to have access to basic necessities which were still limited in a recently post-Soviet Russia. But none of us spoke the language. We all felt like complete outsiders without a community. My parents gave up their professional and social standing in hope of more opportunities for me and my siblings, which we ultimately benefited from. However, at the time, it affected my parents’ sense of identity and limited the emotional support and guidance they could provide. My family and I moved several times throughout my teen years. This made it especially challenging to go through puberty and understand my place in society as a woman, all while feeling the weight of both Russian and American cultures and trying to assimilate. I developed obsessive compulsive disorder and clinical depression by the time I was thirteen, followed by an eating disorder and excessive drinking through college, along with a slew of other unhealthy behaviours and relationship patterns. All of the challenges that I had acclimating to my new environments throughout my adolescence made me want to understand their root causes more clearly. I found that art was a way to explore them. Migrating also gave me a more nuanced understanding and a greater sense of empathy toward marginalised groups, whose treatment by those in power is shaping a lot of the conflicts we’re experiencing today.

You speak of the expectations put on women from a young age. How has your art helped you to process that?

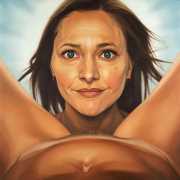

By the age of ten I became aware of my appearance. Or, more precisely, the ‘flaws’ in my appearance. Shortly after, I was aware of my sexuality and what it meant to others, specifically men. I understood early on that as a girl, those two things seemed to trump any other quality I had (besides my disagreeable personality which often got me scolded, but was probably a response to the steady stream of said objectification). Art gave me a voice and an opportunity to regain power and control and eventually the language to understand and communicate my experiences, along with therapy and gender studies. Through my work, I want to portray a heterosexual female perspective that I rarely, if ever, got to see when I was younger; one that’s assertive, unabashed, unapologetic, and clear of internalised misogyny.

What sparks the ideas for your creations?

What sparks the ideas for your creations?

I get a lot of inspiration from reading, from personal interactions or experiences, as well as pop culture and media. I often use found images and sometimes reference other art (quite literally), as a way to give context while making social commentary. Reading, however, helps me understand the context of my experiences as well as my response.

In your view, what does it mean for a woman to have power?

I’d say power means having equal rights, pay, opportunity, and access to healthcare. A woman having power means not being brought down by institutionalised and nuanced sexism. It’s hard not think in political terms as so many of our rights are being infringed upon at the moment, especially for women of colour and lower class women.

What does pleasure mean to you?

Pleasure means connecting to people, emotionally and/or physically, and many, many orgasms with several beer breaks. Possibly followed by a massage or deep slumber.

Who or what has been the biggest influence on your work?

I’m not a fan of superlatives, but I think the biggest influences on my work have been the people around me who have supported and encouraged me along the way. I’m also inspired by other women, artists or not, who go against the grain in any way to get their voice heard, despite all of the pushback, the unpopularity of their opinions, the pure hatred, and the difficulty finding a solid male partner once they’re deemed too successful and threatening to most men.

Alexandra Rubinstein’s website, which includes many more examples of her work and links to exhibitions, interviews and media appearances, can be found here.