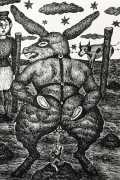

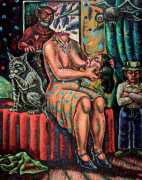

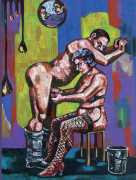

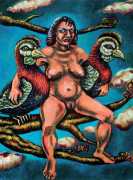

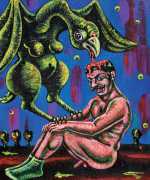

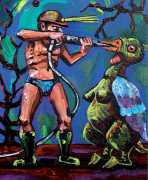

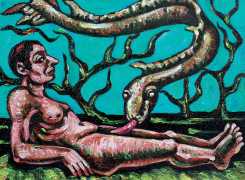

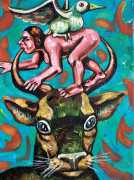

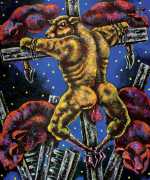

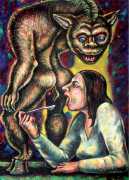

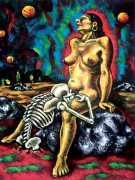

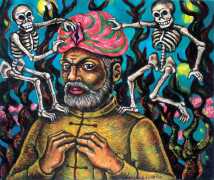

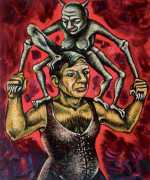

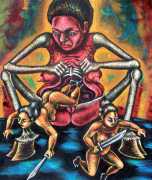

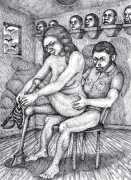

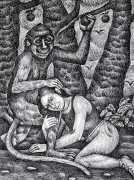

‘With Anne van der Linden there is always a sense of horror, but there is also love everywhere, even in the horror’ – so writes the artist Bruno Richard of the work of this distinctive and original French artist.

Offspring of a German Jewish mother and a Belgian geophysicist father, she happened to be born in England though her family was thoroughly Paris-based. Her mother ran a small antique shop and gallery, which helped kindle her fascination and respect for art, and she started drawing when she was seventeen.

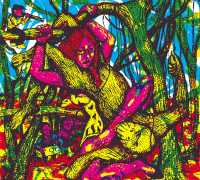

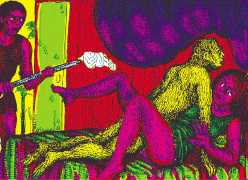

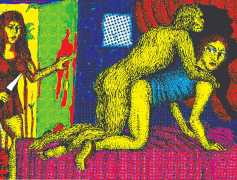

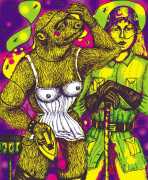

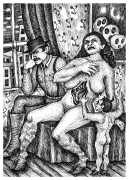

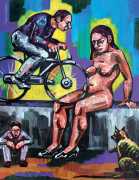

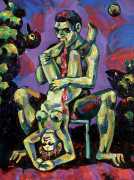

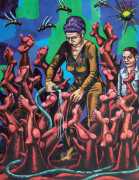

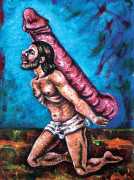

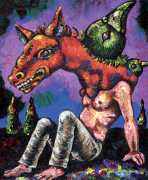

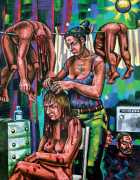

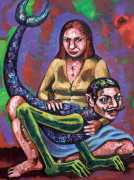

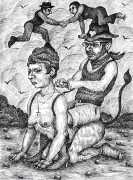

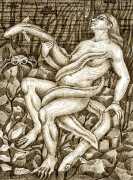

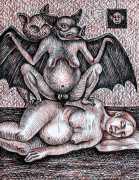

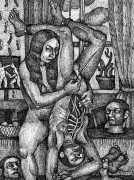

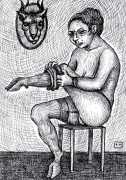

In 1982 van der Linden entered the Paris École de Beaux-Arts, but found the teaching much too formulaic and left after eighteen months. As she explains, ‘I have always had an aversion to anything that was the way “things should be”, including drawing boards and pencils – basically I rejected the status of artist. I did things my way, often accompanied by a haze of hashish. I had a very free way of approaching things, improvising, quite close to what the Surrealists were doing.’ After a period of painting mostly abstracts, in the early 90s her work started to include distorted bodies and limbs in a loose overall structure, wild and highly sexualised, relying heavily on improvisation.

She published her first book, Heavy Meat, in 1995, at which time she began to exhibit regularly. ‘I got a little lost in the search for formal purity,’ she explains, ‘and little by little I felt the need to reintroduce figures and narratives, to tell my stories through the arrangement of colours on the canvas rather than creating “concepts” for galleries.’

Between 1983 and 2007 she worked regularly with the avant-garde performance artist Jean-Louis Costes, with whom she co-founded the review La vache bigarrée (The Brindled Cow), and in 1994 Éretic Art, a platform for publishing and distributing underground works. She created sets for Costes’ musical performances, and participated in some of his plays and films. Together they published Systèmes sexuels (Sexual Systems, Éditions Monotrash) in 1995 and Amour m’a tué (Love Killed Me, Éditions Chacal Puant) in 1996.

Other collaborative projects include working with the pop artist Olivier Allemane to create the review Freak Wave in 2008, and with the poets June Shenfield (Tais-toi et bande, Shut Up and Get It On, 1997), Jérôme Bertin (Histoire d’os, Bone Story, 2009) and Nina Živančević (Sous le signe de Cyber-Cybèle, Under the Sign of Cyber-Cybèle, 2009).

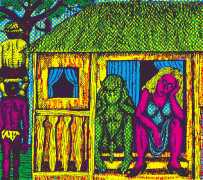

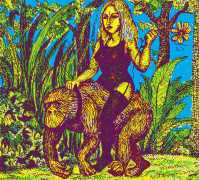

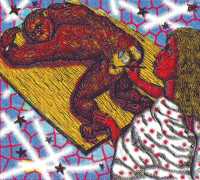

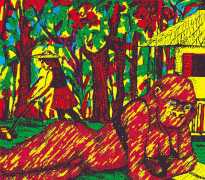

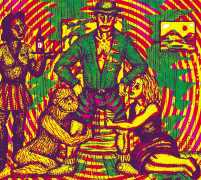

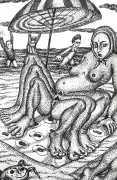

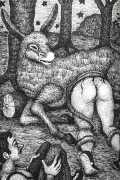

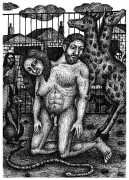

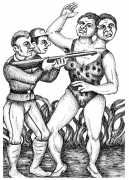

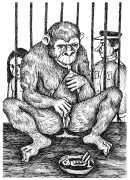

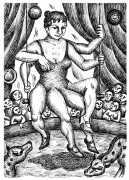

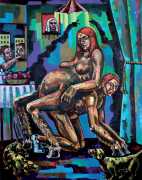

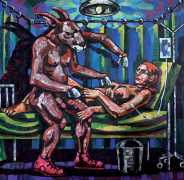

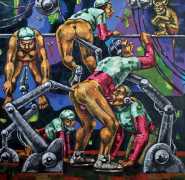

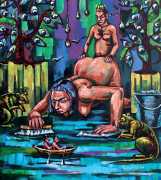

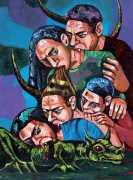

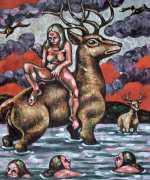

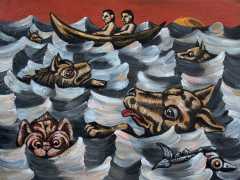

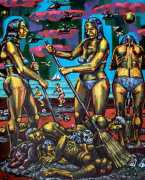

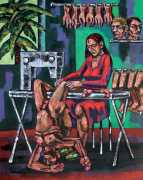

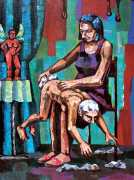

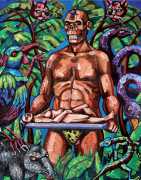

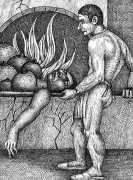

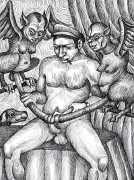

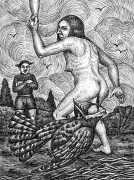

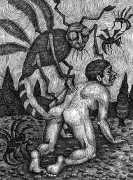

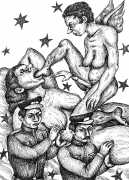

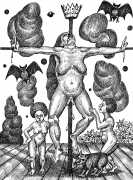

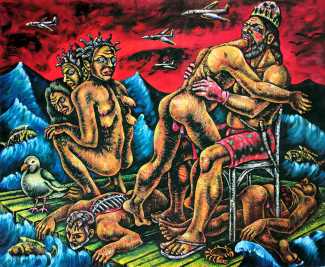

Anne van der Linden’s drawings and paintings reveal the teeming bowels of a world in a state of horror. They remind the viewer of violent engravings in eighteenth century travel accounts, of the German Expressionist artists who described the madness of war, or of Géricault, to whom she pays magnificent tribute in her 2016 version of ‘Le radeau de la Méduse’ (The Raft of the Medusa), echoing the ravages of the Syrian conflict and the drama of migrants, and continuing the great tradition of historical painting while mixing the grotesque with horror, including a cannibalistic king in polka-dot swimming trunks and flip-flops.

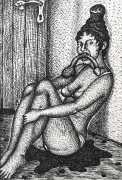

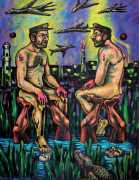

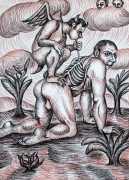

When asked about her inspiration, Anne van der Linden is clear that external influences and internal process are equally important. ‘I let myself respond to external triggers,’ she says, ‘and that creates something of a game with my superego. I try to avoid judgement, to let my brain run into its uncontrolled part, which always offers interesting surprises. Then afterwards I consider and reorganise if necessary. It’s about using all that part of the brain that works like dreaming, without being asked. When I do that I’m always a winner. But I’m not a crude artist, rather an opportunist using the images that result. I never know quite where the inspiration comes from; it’s magic, emerging from an accumulation of layers of experience, and if I can manage to capture something important then it’s a good surprise.’

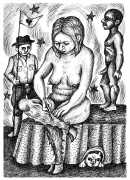

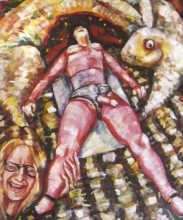

Anne van der Linden’s paintings are based on her lived experiences. ‘Earlier there was more sex, now there is more death, resulting from aging and loss. I notice that when I paint in the summer I paint redder than in the winter. Before the menopause I used a lot of red just before my periods, and I’ve been painting bluer since the menopause. These aren’t the results of conscious will, they’re merely observations. The colours in my painting are linked to sensations, to the state of my body, to the state of my perceptions, a “logic of sensation” as Gilles Deleuze puts it.’

She considers herself a radical libertarian and feminist, working hard not to fall into conventional and moralising discourse. ‘Right-on feminists piss me off,’ she says, ‘the loudmouths always watching you for a wrong word, I can’t stand that. I support the radicalisation of desire, of chosen and affirmed desire. Placing oneself as the point of view of the desiring changes everything. For a woman, desiring is often considered vulgar. It seems to me that if we took things in hand in a more frank way, a lot of positive consequences would ensue. That’s kind of why I create such obscene things. Society has so many taboos, but it seems like I was born to break through them; my psychology insists that I don’t accept them. So I don’t follow most social and artistic conventions. I start from myself.’

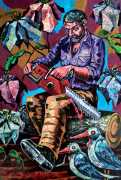

Anne van der Linden lives and has her studio in the leafy northern Paris suburb of Saint-Denis. She exhibits regularly in Paris and beyond, mostly in group shows, where reviewers work hard to understand her style and influences, which according to preference include Dürer, Bosch and Goya, Otto Dix and Max Beckmann, Honoré Daumier and Frida Kahlo, Clovis Trouille and James Ensor, Robert Crumb and Mexican muralism.

Anne van der Linden’s website, with many more examples of her work, can be found here.

If you read French, the extended essay at the end of Anne van der Linden’s Amour vache (Éretic-Art, 2021) by Christophe Bier and Xavier-Gilles Néret (from which much of the above information is derived) is an excellent introduction to Anne’s work and influences.