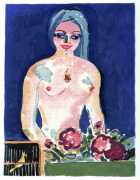

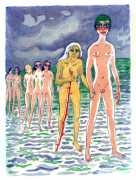

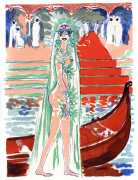

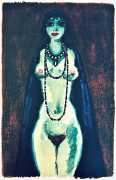

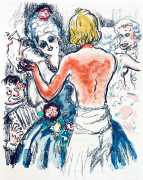

When asked about his popularity as a portraitist with high society women, van Dongen was very clear what mattered most: ‘The essential thing is to elongate the women and make them slim. Then give them beautiful eyes. After that it just remains to enlarge their jewels.’

When asked about his popularity as a portraitist with high society women, van Dongen was very clear what mattered most: ‘The essential thing is to elongate the women and make them slim. Then give them beautiful eyes. After that it just remains to enlarge their jewels.’

Cornelis Theodorus Maria ‘Kees’ van Dongen grew up in Delfshaven, then on the outskirts of Rotterdam. When he was sixteen he started his studies at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Rotterdam, working with Jan Striening and Johannes Heyberg. It was at the Academy that he started a relationship with fellow painter Augusta ‘Guus’ Preitinger, who he married in 1901. In 1897 Van Dongen lived in Paris for several months, and in 1899 he and Guus returned to Paris and took up residence in Montmartre. A son, born in 1901, survived only a few days, but their daughter Augusta, always known as Dolly, was born four years later and became a favourite of the artistic community around van Dongen, especially of Pablo Picasso and his girlfriend Fernande Olivier; for several years van Dongen shared a studio with Picasso at the Bateau Lavoir at 13 rue Ravignan.

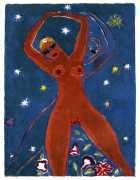

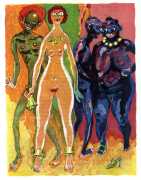

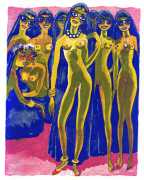

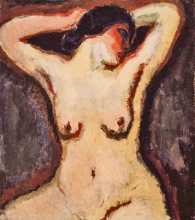

The real breakthrough for van Dongen came in 1905, when he participated in the controversial Salon d’Automne exhibition together with Henri Matisse, André Derain, Albert Marquet, Maurice de Vlaminck, Charles Camoin and Jean Puy. The bright colours of this group of artists led to them being called Fauves (wild beasts) by the influential art critic Louis Vauxcelles. Van Dongen was also briefly a member of the German Expressionist group Die Brücke.

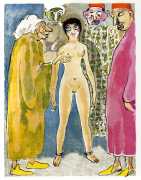

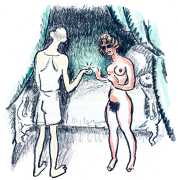

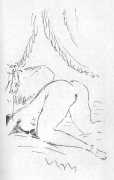

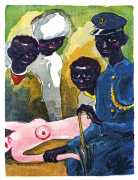

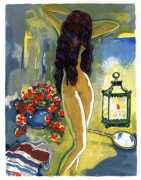

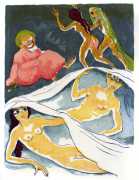

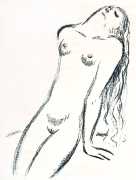

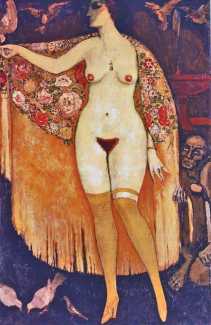

It was after this that van Dongen began to develop a reputation as a socialite. He often hosted masquerade parties, and his art and lifestyle were the talk of the Paris fashionista. His paintings often depicted erotic subjects, which often caused consternation among critics and admirers. One such painting was a nude portrait of his wife Guus, ‘Tableau’, which he completed in 1913; the figure crouching on the floor to the right is Kees, admiring the beauty of his wife. He exhibited the work at the 1913 Salon d’Automne, but the work was considered so scandalous that the police removed it from the gallery. Van Dongen condemned its removal in no uncertain terms: ‘For all those who look only with their ears, what we have here is a completely naked woman. You may be prudish, but I tell you that our genitals are organs as amusing as our brains, and if our sex was found in the face in place of the nose (which could well have happened), where would prudishness be then? Like the lack of respect for many respectable things, shamelessness is the true virtue.’

In the summer of 1914 Guus took Dolly to see family in Rotterdam, but they were caught by the outbreak of World War I and were not able to return to Paris until 1918. It became clear that both before and during the war Kees had been having sexual relationships with several other women, and Preitinger and van Dongen divorced in 1921. Of these liaisons the most important, starting in 1917, was with a married socialite, the fashion director Léa Alvin, also known as Jasmy Jacob, a relationship which lasted until 1927. It was during this period that van Dongen developed the lush colours of his distinctive Fauvist style, which earned him a solid reputation with the French bourgeoisie and upper class, where he was much in demand for his portraits. As a fashionable portraitist, he was commissioned for subjects including Arletty, Louis Barthou, Sacha Guitry, Leopold III of Belgium, Anna de Noailles and Maurice Chevalier.

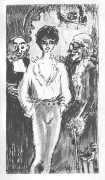

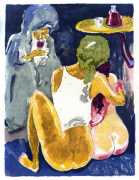

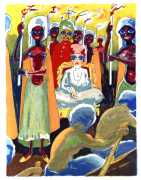

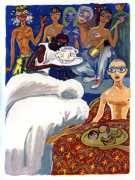

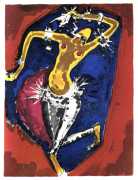

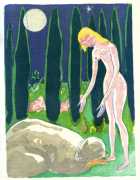

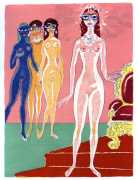

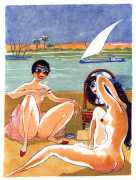

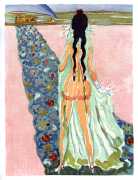

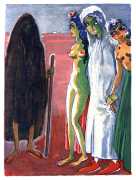

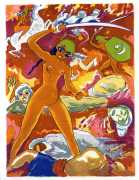

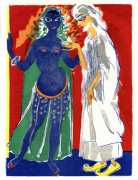

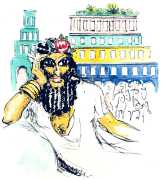

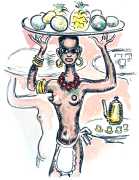

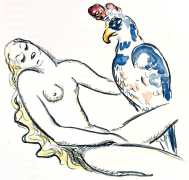

In addition to selling his paintings, van Dongen also gained an income by selling satirical sketches to the newspaper Revue Blanche. Book illustration was also a regular source of work and income; in 1920 Les Éditions de la Sirène commissioned van Dongen to produce illustrations for a new French edition of Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book; the result was some of the most successful illustrations ever made to accompany Kipling’s stories.

In addition to selling his paintings, van Dongen also gained an income by selling satirical sketches to the newspaper Revue Blanche. Book illustration was also a regular source of work and income; in 1920 Les Éditions de la Sirène commissioned van Dongen to produce illustrations for a new French edition of Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book; the result was some of the most successful illustrations ever made to accompany Kipling’s stories.

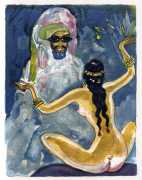

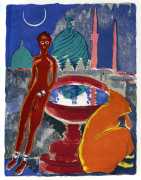

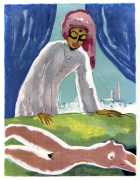

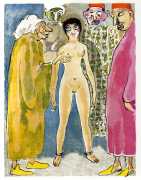

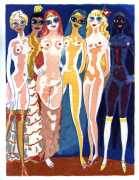

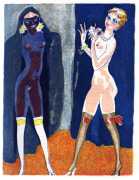

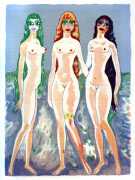

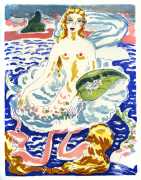

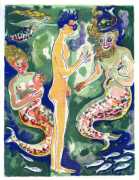

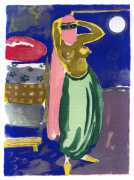

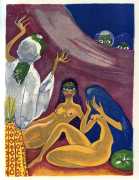

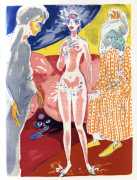

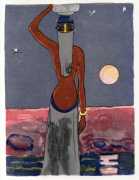

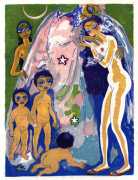

Other book commissions followed, and by the mid-1940s van Dongen was regularly producing illustrations for limited edition books, including Henri de Montherlant’s Les lépreuses in 1947, Marcel Proust’s A la recherche du temps perdu in 1947, Casanova’s Premiers amours in 1950, and to crown his achievement the colourful images for Le livre des mille nuits et une nuit in 1955.

From 1959 Kees van Dongen lived in Monaco, and died in his home in Monte Carlo. Always the avowed self-critic, one of his most-often quoted remarks is ‘Painting is the most beautiful of lies’.