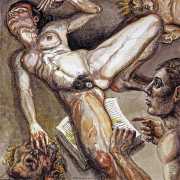

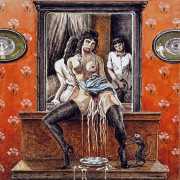

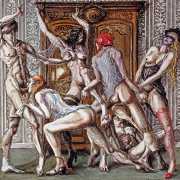

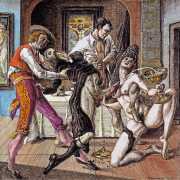

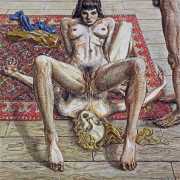

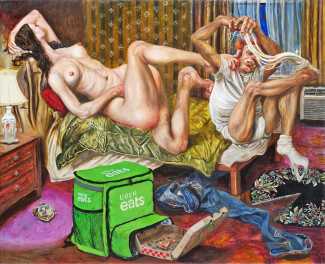

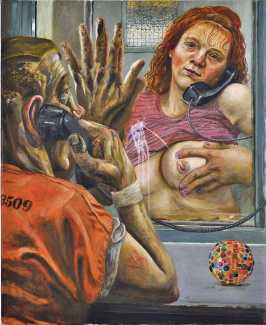

Although at first glance Marcos Carrasquer’s paintings and drawings look surreal, a closer look is enough to discern the artist’s desire to tell recognisable contemporary stories through the medium of his art. It is clear that his canvases, full of diverse elements, do not allow for superficial readings. As he has said of his work, each image should awaken the viewer, shake them, and encourage them to think.

Although at first glance Marcos Carrasquer’s paintings and drawings look surreal, a closer look is enough to discern the artist’s desire to tell recognisable contemporary stories through the medium of his art. It is clear that his canvases, full of diverse elements, do not allow for superficial readings. As he has said of his work, each image should awaken the viewer, shake them, and encourage them to think.

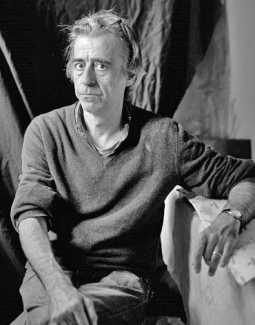

Carrasquer’s family was forced to leave Spain in 1939 after the civil war, during which his father and uncle were exiled and imprisoned. This and the death of another of his uncles on the front line against the German army are important reasons why themes of conflict often appear in his work. Marcos grew up in Hilversum in the Netherlands, and studied painting at the Willem de Kooning Academie in Rotterdam. His first works were mostly abstract, but the documentary painting which forms the core of his work quickly became his favoured style. After his Rotterdam studies he chose to return to Barcelona for a while, and then spent several years in New York before finally settling in Paris, where he now lives and has his studio.

In 2016 Marcos Carrasquer was interviewed by Maria Kyrolopoulou for the Greek online magazine Art22; below we have translated some of the most interesting questions and replies. The whole illustrated interview (in Greek), can be found here.

Tell us how your artistic journey began

As for all painters I believe, out of sensitivity to what is happening around you, the beauty and strangeness of the people you meet. The inner need that leads you to ask questions about everything, and especially about what it is that touches you looking at a landscape, an object or a person. The endless appetite for images, the ‘iconomania’ of painters, the desire to take an object that you see in front of you and to give it a role through art. At some point, after all these external stimuli of everyday life are filtered and fermented within us, producing new images. This is how your perception of the world is born. Around the age of eleven or twelve, when I discovered after many defeats that I would not become a professional footballer, I decided that what I would eventually want to become in my life was a painter.

Time is an important element of many of your paintings. Tell us about your perception of time and history.

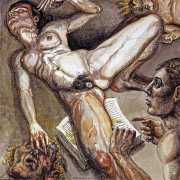

By connecting events from different eras in a composition, I choose to suggest to the viewer my own perspective on the passage of historical time and the recording of what happens and marks it. The mixed historical references therefore come to highlight the importance of a timeless view of history. It is easy to forget what happened in the past, just because it seems to belong there and separates us from it, so it becomes too easy to repeat it again in the future. The repetition of history itself brings to the surface this truth of the timelessness of certain events. My works are, I would dare to say, timeless. Yet history is being constantly rewritten. Each of my works is a meeting point of the past and the present. Thus for example Nazi soldiers can appear in a modern setting, just as my imagination created them.

You have strong views on the role of ‘the artist’; can you tell us more?

My attitude towards the viewer of art is related to the way I work. I have never been interested in preparing drafts. Every element of a painting or drawing emerges as I begin to work on the painting surface. So whatever elements remain until the end, means that they are meant to there and are part of the composition, because they serve the idea that gave birth to it. I am not particularly interested in the role of the artist, because when I arrived in France I saw the response from people when anyone said they were a professional artist. They tended to see ‘the artist’ as rather weird and marginal. Unfortunately, this is also the case with some people in the art world. I was isolated and naive then, and could not imagine what the problem was with ‘art’. I don’t see why I should have much in common with artists as a whole. Every artist has their own role and motivation, especially looking back in history. It might have been as part of a political and religious system. Their art was was often associated with people in power who were not at all interested in art itself, but only in their personal image, their image projected on the surface of each work. This is still the case today. Politicians might say they are interested in culture because there is a ministry of culture, but they are often not at all interested in art itself.

Marcos Carrasquer’s website, with examples of his work and information about exhibitions, can be found here.