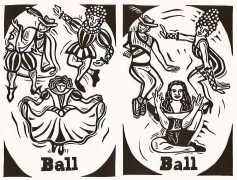

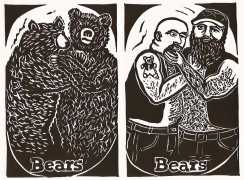

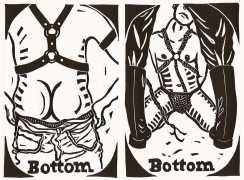

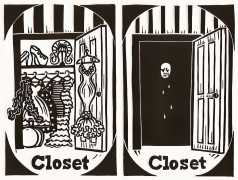

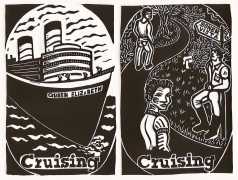

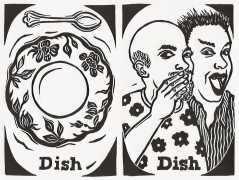

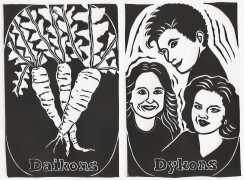

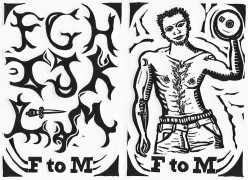

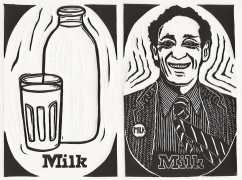

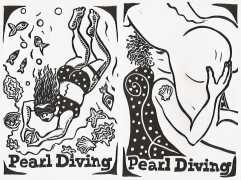

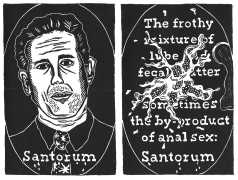

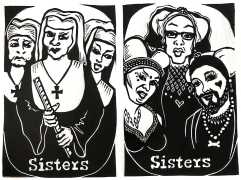

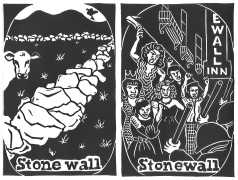

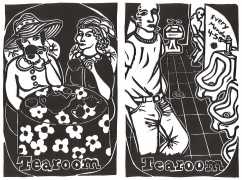

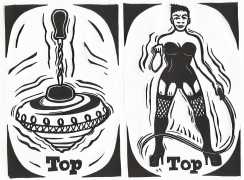

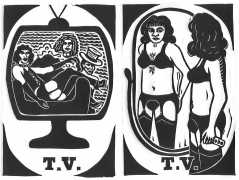

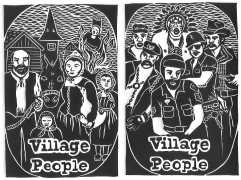

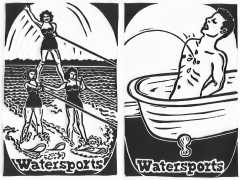

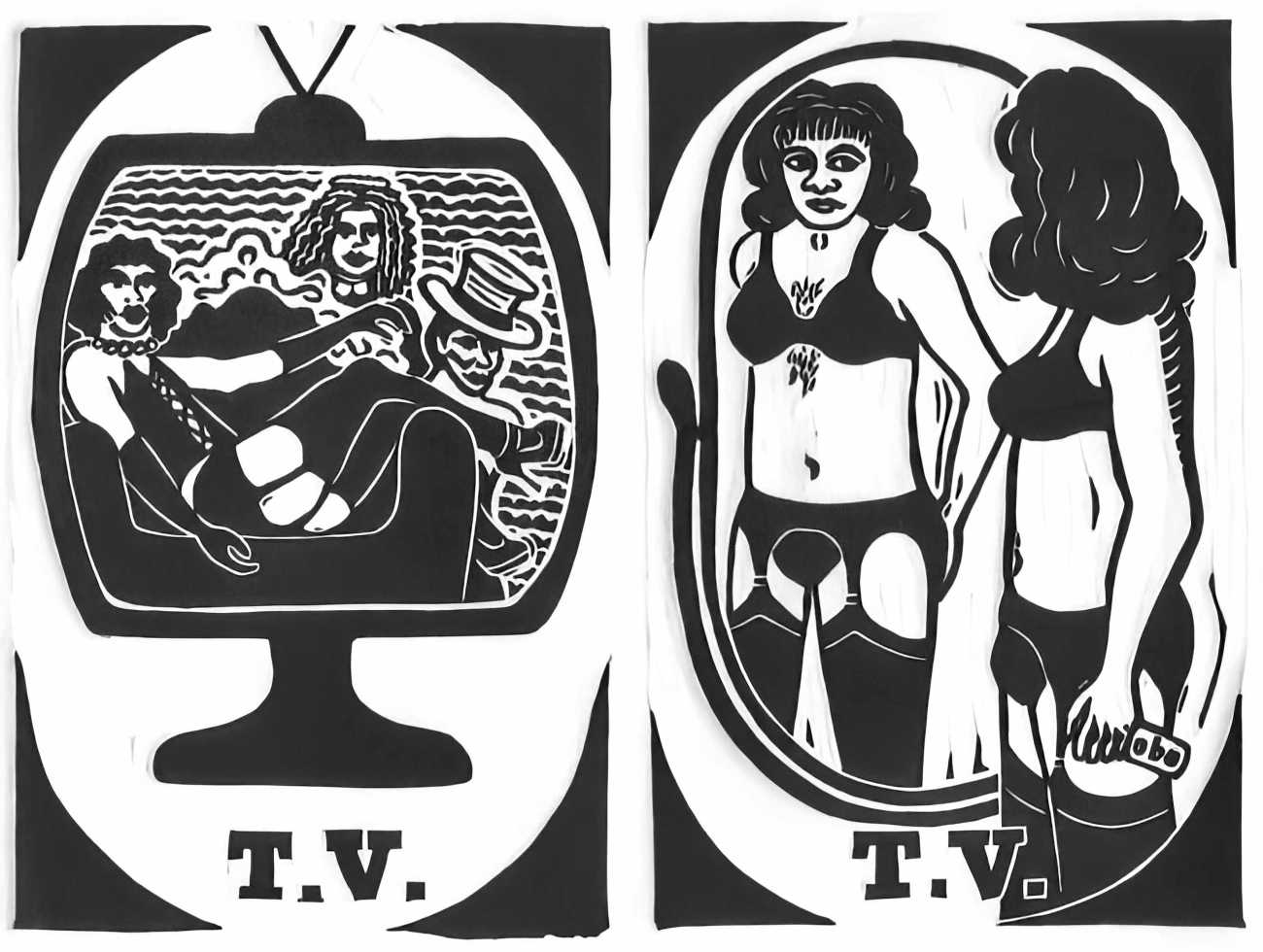

We can do no better than to let Katie herself introduce this wonderful series of linocuts, a project already several years in the making and still ongoing.

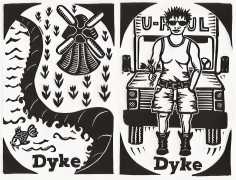

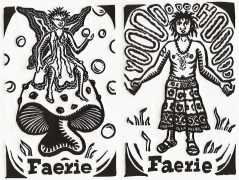

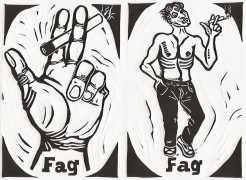

When I titled this collection Queer Words, I meant it in both senses of the term – these are words used in queer communities, and in many cases they are also words that are odd, strange, bent in some way. Several – dyke, fag, faerie – remain venomous epithets in some contexts while functioning as fiercely chosen and hard-won terms of pride in others. To the extent that they become terms of pride, their power to function as epithets diminishes – in this sense they have, quite literally, been bent to serve our purposes. I’m remembering an apocryphal story that went around right at the time lesbians began reclaiming the term dyke. Two women are walking hand-in-hand down the street when someone yells ‘Ya dirty dykes!’ One of the women spins around and shouts, ‘Hey! Who you calling dirty?’

When I titled this collection Queer Words, I meant it in both senses of the term – these are words used in queer communities, and in many cases they are also words that are odd, strange, bent in some way. Several – dyke, fag, faerie – remain venomous epithets in some contexts while functioning as fiercely chosen and hard-won terms of pride in others. To the extent that they become terms of pride, their power to function as epithets diminishes – in this sense they have, quite literally, been bent to serve our purposes. I’m remembering an apocryphal story that went around right at the time lesbians began reclaiming the term dyke. Two women are walking hand-in-hand down the street when someone yells ‘Ya dirty dykes!’ One of the women spins around and shouts, ‘Hey! Who you calling dirty?’

I’ve learned a lot about our queer communities through exhibiting the collections. At one show a man asked what the truck was doing behind the dyke. So I told him the old joke: What does a lesbian bring on a second date? The answer: A U-Haul. He then introduced me to the gay version of that riddle: What does a gay man bring on a second date? What second date?

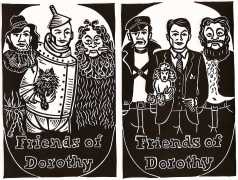

Doing research for these prints was a perpetual delight. I’ve long been fond of the term ‘Friends of Dorothy’, a phrase that appears to have emerged during World War II as a covert way of asking about another’s sexual preferences. It is unclear whether the term originated as a reference to Dorothy Parker or to The Wizard of Oz, but in either case, ‘Are you a friend of Dorothy?’ would sound perfectly innocuous to those not in the know. If the answer was ‘Dorothy who?’ it was immediately clear they weren’t. The term was popular in the 1950s, which I tend to think of as the dark ages of queerdom. It is such a gentle weapon of self-defence, it seems to me, that our predecessors crafted in response to extreme and legally sanctioned homophobia. My fondness for the term increased exponentially upon learning, from Randy Shilts, that it played a role in a naval investigation of homosexuality in the Chicago area during the early 1980s. Upon learning that gay men frequently referred to themselves as ‘friends of Dorothy’, intrepid naval investigators launched a massive hunt for this Dorothy, hoping to persuade her to reveal the names from the massive ring of homosexual military personnel she apparently counted among her friends. The navy never did find her.

These prints poke fun at our various identities, play with stereotypes, allude to tensions between the many communities gathered under the umbrella ‘queer’, and reference our historical and continued oppression as sexual and/or gender minorities. Only once did I receive a complaint about the barbed humour in the prints. I heard, second-hand, that a viewer was offended by my placement of the ‘bi’ trio sitting on a fence. In her view the print evoked the notion that bisexuality is an identity for folks who haven’t yet decided who they really are, implying that bisexuality isn’t a valid choice in and of itself. Indeed, the print does just that – though I hoped that the accompanying image of the trio merrily driving off in a car with an ‘Anything That Moves’ bumper sticker would convey their flippant dismissal of those beliefs, their fence-sitting as a sassy act of empowered choice.

That this print occasioned pain rather than laughter testifies to the extent to which such stereotypes continue to hold sway, to harm, to divide. Only when we’ve digested a painful word or stereotype, embraced it to some degree, are we able to reclaim it – and in that process of reclamation diminish its potential for harm. I would like to think that this collection may, in a humble way, contribute to that process. But for some words, and in some communities, the identities are too hard won: the wounds too fresh to allow reclamation. So I ask you, gentle reader, for your gracious dispensation for touching any nerves that are too raw yet for humour. My intentions are certainly to skewer our precious identities, and I do so with deep respect and gratitude for the ongoing struggle to forge these identities and the communities they enable.

Our queer words are a record of creative resistance. In A Restricted Country Joan Nestle tells of a dyke bar in fifties New York City that posted a guard at the bathroom door to enforce its harsh one-occupant-at-a-time policy, resulting in a perpetual queue that spiralled around the bar. As Nestle tells it, a line act developed in that spiral of queer bodies, a joking, cruising, strutting, boldly creative acting-out of proud butch and femme style: ‘We wove our freedoms, our culture, around their obstacles of hatred.’ So many of our queer words were similarly forged of necessity in the harsh realities of homophobia. Whether retooled epithets, secret codes, or identities embodying alternative ways of being, each in some way carries the traces of our collective struggles. Our queer words are, in that sense, the flowers of our oppression, the fruits of our resistance. So consider this a bouquet to our fabulousness.