L’inflation sentimentale (Sentimental Inflation), considered by many to be Laborde’s best set of illustrations, came about through a fortuitous set of circumstances. At the end of the First World War Laborde was in a poor way. He had been invalided out of the army, badly gassed and drinking heavily. He had lost two brothers and his close English friend Cooper during the war, and his drinking led to the end of his short-lived marriage to René Ferreau and separation from his young daughter Iolanda. He had lost his health, his earning ability, and a host of illusions.

L’inflation sentimentale (Sentimental Inflation), considered by many to be Laborde’s best set of illustrations, came about through a fortuitous set of circumstances. At the end of the First World War Laborde was in a poor way. He had been invalided out of the army, badly gassed and drinking heavily. He had lost two brothers and his close English friend Cooper during the war, and his drinking led to the end of his short-lived marriage to René Ferreau and separation from his young daughter Iolanda. He had lost his health, his earning ability, and a host of illusions.

But he could still draw, and he still had his Montmartre friends and colleagues, including Francis Carco and Pierre Mac Orlan. In April 1922 La Renaissance du Livre was set up to produce high-quality illustrated books after the war had resulted in an almost complete collapse of publishing; Louis Theuveny was appointed as general manager and Pierre Mac Orlan as artistic advisor. One of the first things Mac Orlan did was to put together a series of short essays about Paris social life, commissioning Laborde to produce illustrations to accompany them.

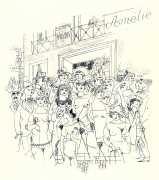

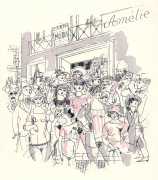

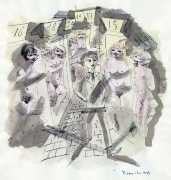

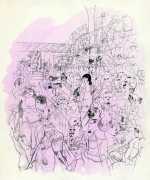

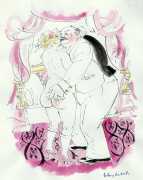

As Mac Orlan wrote in the introduction, L’inflation sentimentale set out ‘une maison de plaisir de pure imagination, celle que chacun nous possède dans sa tête fragile et dont on verra bien, un jour, les résultats terrifiants’ (‘a house of pure imaginary pleasure, one which each of us has in our fragile head, and the terrifying results of which we will one day become aware’).

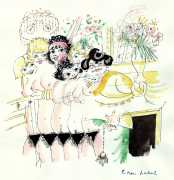

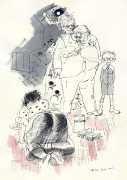

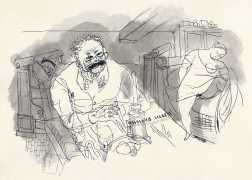

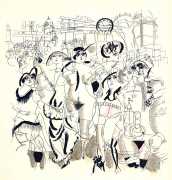

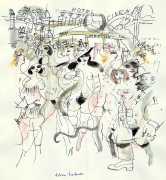

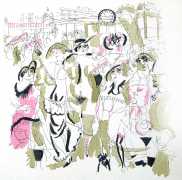

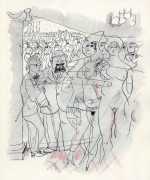

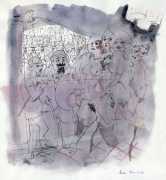

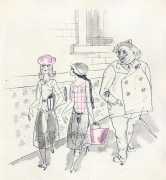

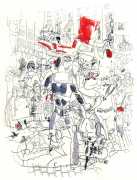

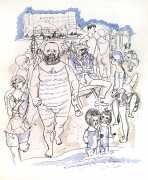

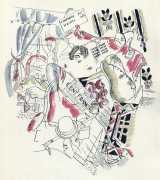

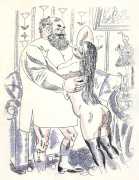

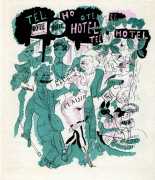

Chas Laborde’s vivid illustrations, which more complement Mac Orlan’s themes than illustrate the text, depicting a world ruled by lust, superficiality and fantasy. His overarching pessimism is obvious; the world is a gigantic mess. Here is the good father of a family who, while reading the news, is also eyeing his daughter going to bed while his wife sleeps. There is the suited gentleman, Legion of Honour in evidence on his chest, who mentally undresses the two schoolgirls crossing his path. The critic Pierre Mornand mused that ‘He seems to have a universal obsession with sex, representing it in dream images that haunt our sleep, chasing us, indefinitely repeated in multiple mind-blowing forms. But, not surprisingly, these drawings speak. They don’t scream, they seem to whisper relentlessly the same obsessive thought, the maddening desire.’

In many of the drawings it is easy to see the influence of George Grosz, who Mac Orlan admired and introduced to Laborde, but as the artist and critic he painter Adolf Hallman explains, ‘Grosz is harder and drier than Laborde. He lacks the sense of colour in his black and white work. His emphasis on the social programme and the class struggle take up too much space in his drawings, make them look greyer, kill balance and artistic intuition. Grosz is a natural force, interesting, but raw and roughly shaped. Laborde’s vision is much broader, and has a lightness and humour missing in Grosz.’

In 2006 the J.-C. Bellier Gallery put up for sale the original ‘recently rediscovered’ drawings for Laborde’s illlustrations. They appear to have been preserved by the publisher Henri Jonquières, and include several drawings which were not included in the book as published. We include here some of those drawings alongside the illustrations as published, which demonstrate Laborde’s working technique and different colour versions of several of them.

L’inflation sentimentale was produced by La Renaissance du Livre in a limited numbered edition of 140 copies.