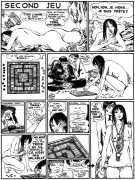

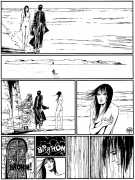

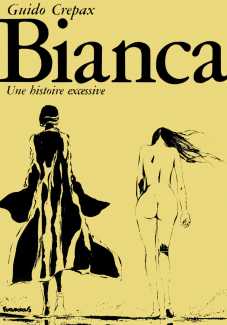

Created between 1968 and 1973, Bianca is probably the most whimsical and psychedelic work in the Crepax canon. Like ninety per cent of Crepax’s work, it is constructed around a central female character trapped in a series of sexual fantasies and adventures, and like Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbie’s Lost Girls, Bianca is more concerned with artistic execution than with sexually arousing its audience. For the most part Bianca fails as porn; if it were more successful as porn it would probably be in print in English. The book’s main purpose is the head-splitting gymnastics Crepax pulls with the comic format.

Created between 1968 and 1973, Bianca is probably the most whimsical and psychedelic work in the Crepax canon. Like ninety per cent of Crepax’s work, it is constructed around a central female character trapped in a series of sexual fantasies and adventures, and like Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbie’s Lost Girls, Bianca is more concerned with artistic execution than with sexually arousing its audience. For the most part Bianca fails as porn; if it were more successful as porn it would probably be in print in English. The book’s main purpose is the head-splitting gymnastics Crepax pulls with the comic format.

Bianca is also significant because it encapsulates what was going on in comics during the late 1960s and early 1970s. It’s a very playful work, even the bondage elements. The narrative highlight of Bianca is the section with the heroine trapped in her shower with a clogged drain. Water rises rapidly and threatens to drown her before she grabs some scuba gear and finds herself in an ocean. There she runs into a zombie Blackbeard who shoots her out of a cannon. From there, Bianca is captured by talking fish, who in turn feed her to Moby Dick. Now inside the whale, Bianca meets Captain Ahab, who is almost immediately shot by Puss in Boots, who then abducts Bianca and sells her to a circus where she becomes part of a tigers-jumping-through-hoops act. All of this happens in fewer than twenty pages, which would be about ten years’ worth of work in an Avengers comic. What is especially fascinating about the sequence is how seamlessly all the disparate events blend together. This section of Bianca is something to behold, like a great DJ set in which all kinds of disparate elements are remixed and reclaimed in order to create a distinctly original experience. This is one of the real gifts that Crepax had as a storyteller, and a core element in all of his work. He was nothing if not a literary mixologist.

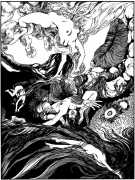

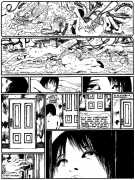

Other highlights of Bianca are the insane dream montages within the narrative sections. These are where Crepax lets loose with his brush, playing with texture and form in a way that is completely wild and uninhibited, even in comparison with his other works. There aren’t many comic artists who are interested in these kinds of elements today. It’s interesting to see Crepax to do it and pull it off with such aplomb, especially given how many of the strengths in his work come from his skill with panelling. Panel or no panel, Crepax had a gifted eye for the time and space necessary to work the comics medium to its fullest. He created other montages in Emanuelle and Valentina, but none of them are as exciting as the ones in Bianca. Montage is an interesting concept in comic book form because comics are a medium based around time and space as presented in sequence on a page. Usually this is expressed mainly through panelling, so it’s remarkable when an artist expresses time through perspective and composition and not just through panels. It opens up the possibilities of the page and shows a kind of wild liberation. In Bianca there are pages where the panelling is far beyond what most artists seem capable of conceiving for the page. His technique goes beyond the grid, which is maybe why some of his more straightforward, less experimental peers like Manara have received much more recognition.

This brings us to the real tragedy of Crepax’s work. For many years Bianca was only available in French, and even now English-language readers can only read it in an expensive and out-of-print anthology. Anglophile audiences who wish to read Crepax are limited to chasing overpriced out-of-print books, or performing Google searches and piecing the comics together from there. It’s a pathetic and damning state of affairs for work that is so important, and could potentially shape the visions of young creators starting out today.

The text above is an edited extract from a blog by Sarah Horrocks which appeared on the Comics Alliance website in September 2012; you can read the whole blog here. The English-language version of Bianca she refers to was published in the anthology Emmanuelle, Bianca and Venus in Furs, Taschen Evergreen, 2000. The version we include here is the French edition, published by IDEA in 1976.