Louis de Gonzague-Frick (1883–1958) was quite a character. He spent most of his childhood in Monaco, where his father edited a financial newspaper and his mother spent much of the time in the casino. Educated at home, he discovered a deep love of language, and wrote poetry in which he freely invented words and expressions, neologisms built on Greek or Latin foundations. His poems, prose and letters were strewn with obscure words with secret meanings, refinements of language delivered in the most serious and sententious tone. He created ‘schools of thought’ including Lunanism (the name of the street in Paris where he lived) and a form of Druidism. He borrowed from other poets – symbolists, decadents and surrealists – often forcing their words to the point of caricature. He wrote of the ‘centoripin of isorrhopic morphologies’ and the ‘elemosinary marvel’.

Louis de Gonzague-Frick (1883–1958) was quite a character. He spent most of his childhood in Monaco, where his father edited a financial newspaper and his mother spent much of the time in the casino. Educated at home, he discovered a deep love of language, and wrote poetry in which he freely invented words and expressions, neologisms built on Greek or Latin foundations. His poems, prose and letters were strewn with obscure words with secret meanings, refinements of language delivered in the most serious and sententious tone. He created ‘schools of thought’ including Lunanism (the name of the street in Paris where he lived) and a form of Druidism. He borrowed from other poets – symbolists, decadents and surrealists – often forcing their words to the point of caricature. He wrote of the ‘centoripin of isorrhopic morphologies’ and the ‘elemosinary marvel’.

His affectations extended to his attire and behaviour. While serving in the French army in 1914 for example, he insisted on wearing white gloves and a monocle. Each morning he would go to his poet-friend Guillaume Apollinaire’s home in formal dress to present him solemnly with an apple on a silver tray.

In 1921 Gonzague-Frick put together a small collection of five erotic poems which he titled, typically obscurely, Le calamiste alizé, which translates as The Scribe of the Trade Winds, the calamus being the reed pen of the ancient world. It was published, unillustrated, in an edition of 150 copies by the Paris publisher Simon Kra.

By 1938 the poet had fallen on hard times, and his health was failing; he had even briefly been interned in an asylum on the orders of a doctor who took his precious language as a symptom of cerebral disturbance. Now in his late fifties, and remembering his lost youth, he added a further three poems to Le calamiste alizé and turned to his even-older friend Brouet for illustrations to accompany the text. Thus was created this uniquely idiosyncratic self-published pink offering.

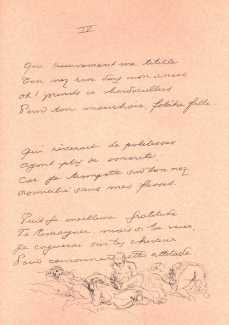

With Gonzague-Frick (metaphorically if not actually) looking over his shoulder, Brouet engraved the poems in free and sloping handwritten script, then added the images, sometimes overlapping them with the foot of the text. It was a deliberate attempt by both poet and artist to break free of the imposed formality of the printed page. The pink Ingres paper and the loose-leaf format tied with a red ribbon added to the hand-made feel of the finished article, and the limited edition of just 65 copies (to the poet a ‘magic’ number) made it more of an artwork in its own right than a ‘book’.

With Gonzague-Frick (metaphorically if not actually) looking over his shoulder, Brouet engraved the poems in free and sloping handwritten script, then added the images, sometimes overlapping them with the foot of the text. It was a deliberate attempt by both poet and artist to break free of the imposed formality of the printed page. The pink Ingres paper and the loose-leaf format tied with a red ribbon added to the hand-made feel of the finished article, and the limited edition of just 65 copies (to the poet a ‘magic’ number) made it more of an artwork in its own right than a ‘book’.

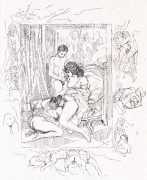

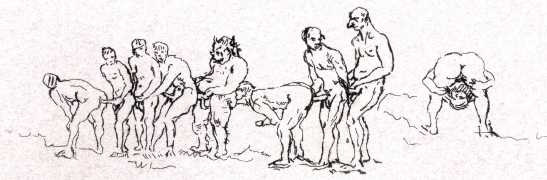

The Brouet images are among the freest and most explicit he ever produced, featuring groups of both sexes disporting themselves sexually in almost every way conceivable.

We have chosen to extract the eleven images from Le calamiste alizé and show them on a white background (at least one copy does exist on white paper) in order to demonstrate Brouet’s skill in engraving. If you would like to see the whole production on pink paper, you can see it here.

If you read French there is a fascinating article about Le calamiste alizé on the Auguste Brouet Journal website, which you will find here.