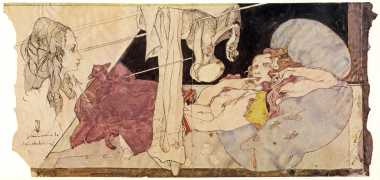

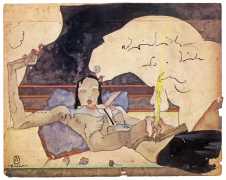

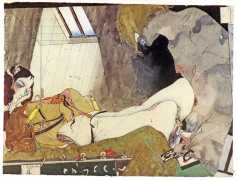

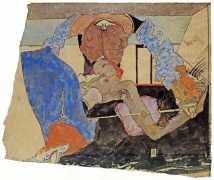

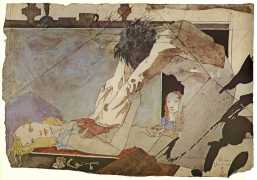

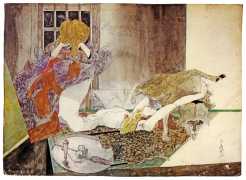

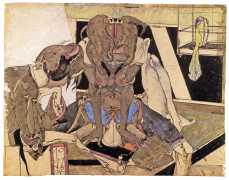

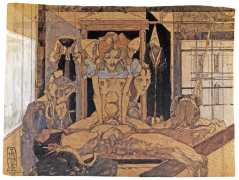

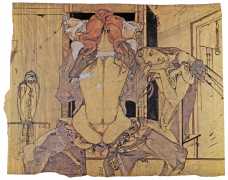

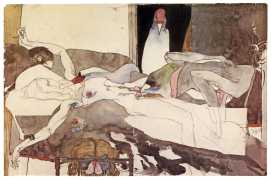

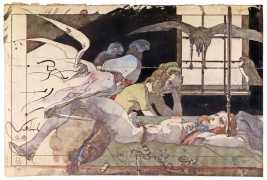

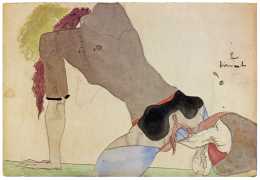

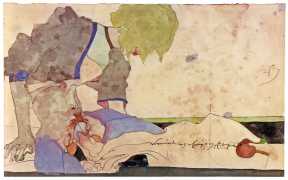

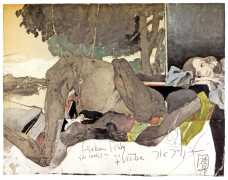

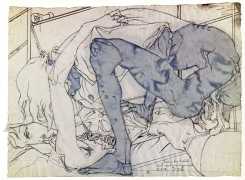

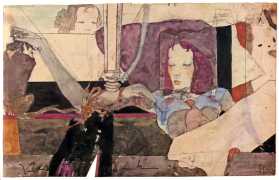

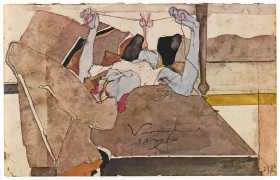

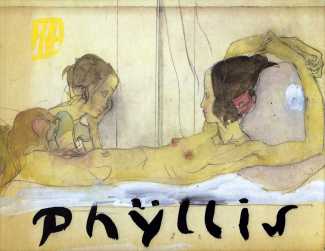

Janssen’s third and last marriage was with Verena von Bethmann-Hollweg, and lasted from 1960 to 1968. The next decade, one of his most productive artistic periods, was also his most sexually active, his lovers including Gesche Tietjen, Roswitha Hartung, Bettina Sartorius, Birgit Jacobsen, Viola Rackow, Kerstin Schlüter, Annette Kasper, Britta Kerinnes and Heidrun Bobeth. Verena, she of the perfect arms, remained a constant memory, however, and the Phÿllis series of paintings, made between late 1977 and mid-1978, makes reference to a remark she made to him after a holiday on the island of Sylt, where she told him that ‘he couldn’t do watercolours properly’. The immediate muse for the series, however, was Birgit Jacobsen, and Janssen said of the paintings that ‘the hand, not the brush, was guided by the memory of Birgit’s anatomy’.

Janssen’s third and last marriage was with Verena von Bethmann-Hollweg, and lasted from 1960 to 1968. The next decade, one of his most productive artistic periods, was also his most sexually active, his lovers including Gesche Tietjen, Roswitha Hartung, Bettina Sartorius, Birgit Jacobsen, Viola Rackow, Kerstin Schlüter, Annette Kasper, Britta Kerinnes and Heidrun Bobeth. Verena, she of the perfect arms, remained a constant memory, however, and the Phÿllis series of paintings, made between late 1977 and mid-1978, makes reference to a remark she made to him after a holiday on the island of Sylt, where she told him that ‘he couldn’t do watercolours properly’. The immediate muse for the series, however, was Birgit Jacobsen, and Janssen said of the paintings that ‘the hand, not the brush, was guided by the memory of Birgit’s anatomy’.

The Phÿllis paintings (the title apparently came from the editor of an erotic art exhibition catalogue that Janssen was particularly struck by) were put on one side for seven years, until Janssen’s great friend and Hamburg gallery owner Hans Brockstedt suggested that the time had come to exhibit them and produce a book based on the paintings.

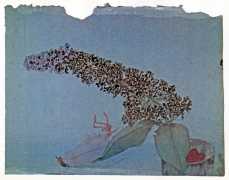

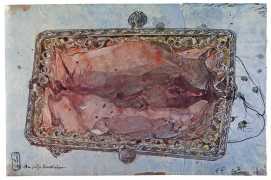

As with all his books, Janssen was very particular about exactly how his work was to be shown, and Phÿllis is no exception. The edition is beautifully designed, including several pages of stark monochrome images on a dark blue wove paper, and many of the images have Latin captions which are no doubt significant to the artist.

There is also an art-philosophical preamble, written by Janssen, intended to provide context for the series, but serves mostly to add to its subtle mystery. A sample follows:

The mechanism of love requires ambition, serious effort, patience and wit. The observing eye is then required for the implementation of this mechanism, which divides the whole into its parts, subdivides it, on the one hand increasing it by adding a lustful gaze to the pleasure of the understanding hand, on the other hand for the control of pleasure. It seems important to me that love should not have a place in what is happening here. Love should be taken for granted and delivered later; love is in the hours where you walk hand in hand, when you eat together, read to each other, plan together and against each other. That is the way of love. But when we consider the physicality, the anatomy, we should as far as possible forget us + other, because the natural tenderness of love opposes the essence of making love. The anatomical connection and the merging of bodies presupposes a tremendous amount of opposition – there is a mutual longing for power, for the domination of the opponent. This desire for power is common to all bodies in equal measure. The images in this book portray something of this – to those who have forgotten although they partake of it, to those who have forgotten because all their strength has been drained, and to those who can never forget it. And everything has its time. Amen.

The mechanism of love requires ambition, serious effort, patience and wit. The observing eye is then required for the implementation of this mechanism, which divides the whole into its parts, subdivides it, on the one hand increasing it by adding a lustful gaze to the pleasure of the understanding hand, on the other hand for the control of pleasure. It seems important to me that love should not have a place in what is happening here. Love should be taken for granted and delivered later; love is in the hours where you walk hand in hand, when you eat together, read to each other, plan together and against each other. That is the way of love. But when we consider the physicality, the anatomy, we should as far as possible forget us + other, because the natural tenderness of love opposes the essence of making love. The anatomical connection and the merging of bodies presupposes a tremendous amount of opposition – there is a mutual longing for power, for the domination of the opponent. This desire for power is common to all bodies in equal measure. The images in this book portray something of this – to those who have forgotten although they partake of it, to those who have forgotten because all their strength has been drained, and to those who can never forget it. And everything has its time. Amen.

This probably tells us as much about the artist as about the highly original, disturbing and imaginative paintings.