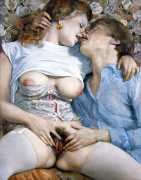

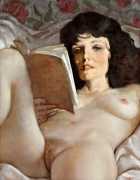

Over the years Currin has painted dozens of images of people, mostly women, having sex. It helps to know that he rarely paints from life, his favourite inspiration being magazine and catalogue photographs, many of them pornographic (his collection tellingly includes a number of vintage Color Climax magazines), which he projects onto the canvas to use as the basis for his fanciful compositions.

Over the years Currin has painted dozens of images of people, mostly women, having sex. It helps to know that he rarely paints from life, his favourite inspiration being magazine and catalogue photographs, many of them pornographic (his collection tellingly includes a number of vintage Color Climax magazines), which he projects onto the canvas to use as the basis for his fanciful compositions.

In a 2011 interview, Currin described his relationship to his work as ‘a completely ambisexual atmosphere. If there’s a logic to my work it’s that the pictures of men are about men and the pictures of women are about me’. It’s interesting that so few of his critics have taken this self-assessment and explored it with the artist; it would almost certainly be more fascinating and insightful than the many comparisons with Vermeer and Goya upon which most of his (male) interviewers have concentrated.

As Currin so candidly admits, each viewer’s response to these over-realistic sex scenes tells as much about artist and viewer as it does about sexual intimacy, a relationship inevitable influenced and modelled by the photographic material used in the creation of each painting. Are his paintings sexy? Are they erotic? Are they pornographic? Are they honest? Are they good? Only you can judge.

To balance the many male assessments of Currin’s art, there have been a couple of searching analyses by women commentators, intelligently questioning both the artist’s work, and perhaps more importantly why it strikes such a strong chord with the predominantly male world of ‘serious art’.

Here is Ann Lauterbach’s 2005 piece, John Currin: Pressing Buttons, from the New England Review, Volume 26, Number 1.

John Currin: Pressing Buttons

With John Currin, whose midcareer retrospective at the Whitney Museum recently closed, movers and shakers of the art world again yielded to the seductive strut of a badboy wunderkind hawking new toys. This time a dirty-blond Yaley with 24th Street smarts, a fashionista wife, and a baby with balls, showing his prowess with painterly technique, appropriated Old Masterish composition, and transgressive subject matter.

Currin’s paintings tell of a soured American idealism, of a sacred native goodness fallen to a curdled profane. Where once there were John Singer Sargent’s luminous portraits of long imperious women in satin dress, now there is haggard and disappointed Ms Omni (1993), her eyes dully sated. Where once there were Norman Rockwell’s scenes of domestic coziness, or Andrew Wyeth’s calendar-perfect rural landscapes, now there are strained encounters with suburban domesticity gone awry and astray. Wyeth’s talismanic, if mawkish, Christina has turned, long tresses bleached blond, Deane-eyed as a Paris Hilton doll, to face ‘her’, that is our, world. Where once there were Warhol’s portraits of a transfigured, mythic Marilyn, now there is the ordinary face of TV star Bea Arthur above an ordinary middle-aged American woman’s naked torso. Where once high aesthetic technique and inventive finesse – say Johns, or Guston, or de Kooning – stood for a complex and replete Americana, now it serves the dubious retro-fit of a canny virtuoso. This isn’t Kansas anymore, nor the magical mystery tour of urban New York; we’re in a redundant faux Oz, where the wizard is Larry Gagosian and the magic is the sound of rushing casino coin. This is George W. Bush’s America, where, according to the New York Times, we are back in the culture wars big time. I don’t quite buy the idea of the ‘grotesque’ which such stellar critics as Robert Storr and Robert Rosenblum are promoting as a way to think Currin. It feels too much like a means to insinuate a troubling oeuvre into the fabric of historical narrative. Of course we cannot argue that the work doesn’t come from someplace, no one wants to claim that kind of originality anymore, but the grotesque doesn’t seem quite right. I think Currin is closer to a reactionary social critic, a kind of Vanity Fair guy who listens to Howard Stern while he writes insider scoop. He has some of the simplistic shtick of the maven of shock, where attitude is everything, putting the other at a disadvantage by the sheer force of the in-the-know putdown. Currin has something, too, of the cartoonist’s distorted mark, and of the pop pornographer’s detached voyeurism – Hugh Hefner’s friendly stare. But his work lacks the torque either of true parody or of satire; it’s too perfunctory, too silly and obvious, not droll and trenchant like, say, R. Crumb, or Jeff Koons at his best. One might evoke Hopper, but there is not a shred of pathos in this work, and neither is there nostalgia for a lost anything.

Many of Currin’s female subjects have the same stilted smile and vacuous stare, lifted from advertising; his work seems joyless, sarcastic, and glib, and it is difficult to come round to the idea that he is actually sympathetic to the curiously inadvertent subjection of his subjects (one could think here, perhaps, of the roiling conversation around Diane Arbus’s freaks). Something about this work makes us feel creepy and embarrassed, as if we were caught like a teenager rummaging in our parents’ underthings; we feel awkward; ashamed and giggly. This is not only for the obvious reasons found in such macabre works as The Wizard, depicting a gloved Howdy Doody-esque figure groping, or manipulating, the immense breasts of a blond, it is pictures like Minerva and The Activists, where Currin’s disdain is crudely palpable. Minerva, otherwise known as Athena, Goddess of Wisdom, is show as an hysterical crone with maple leaves stuck in her hair; the ‘activists’ are pathetic seniors, grandmas and grandpas left behind in the millennial dust. (It is no stretch to imagine this picture in the living room of, say, Donald Rumsfeld. Well, someone had to attract those big Republican bucks.)

Currin’s claim to fame seems to be an adolescent’s sense of uncouth subversion combined with the student’s desire to ingratiate his teachers. The straight married white guy will make spoofy pictures of gay couples in domestic bliss, of overly endowed middle-aged women; he will portray young African American women and flimsily dad silk-skinned ingénues; he will insinuate his own features onto those of a girl, playing with sexual identity as if it were a sort of New Age set of Lego . He will portray Nadine Gordimer, the South African Nobel laureate, with a huge head, lachrymose and overburdened on a desexualized, emaciated body. He will take the iconic thin society matron and show her to be a grim combination of material privilege, vanity, and spiritual destitution.

Compositionally, Currin’s work is often stilted and vapid; interior pictorial space is broken up by edges of mirrors and frames, bland objects, and traces of vague landscape elements which do nothing to conduct or connect the viewer’s eye into a circuit of details that might lead to an interpretive insight. His figures are adrift in an uninflected habitat without anything that signals their personal sense of belonging: work, house, landscape. They abide in a drained, inanimate, placeless place, a shopping mall of the soul. Further, the three features where portraiture is traditionally revelatory of a subject’s character – hands, eyes, and mouth – are remarkable in Currin for their homogeneity. His subjects’ hands, in particular, are invariably slender, long-fingered, and limp (male or female), as if drawn from studies of mannequins for women’s gloves. Currin excels, however, at the details of garb: his brush finds nuance in the ribbings, texture, and drape of cloth. (There is good reason why his name is dropped so frequently on the fashion page of the New York Times.) At the heart of all Currin’s images is a platitudinous superiority that houses a distaste for the difficult uncertainties of intimacy or attachment. The yellow-brown murkiness of his palette drains vitality; his head-shot portraits merge into one ubiquitous stare. None of his subjects is animated by the individuation of personal agency; they all seem, even those who are not ‘invalid’, halted, inert. Under this inertia is a sense of impending violence. One imagines his next body of work to be themes of mayhem and slaughter, when the comparisons to Goya will be more apt.

But what about Currin’s much touted painterly expertise? These claims seem grossly exaggerated, brought about by deprivation, as if everyone had been starving and someone came up with some carrot sticks. There are countless passages in this work which look both uncertain and overwrought; his surface is by turns glossy and built up, pocked; often he seems unsure of the relation between drawing and paint. In any case, contra McLuhan’s mantra, here the medium is decidedly not the message. It is precisely the disconnect and clash between Currin’s attention to, and proclaimed love of, the act of painting, and the crude assertiveness of his subjects, that captures our attention, confuses our habits of seeing. Like a pirate, he steals booty off the good ship PC and sails off on a sleek old schooner, replete with polished teak and brass fittings. (Those naked Fishermen in their laden dinghy are headed out to a very cool yacht parked at the Vineyard. Trust me.) He has hoisted the academic flags of post-gender feminist-colonial-multiculturalisms on their own postmodern discourse-saturated petards, all the while letting the ship fill with the brine of an ostensible universality. For Currin, equality is not a complex ratio of opportunities, but a flat transaction, an economy of reductive semblances. Currin’s in-your-face rejection of ideology and theory-driven models for art experience is, I think, what has caused aestheticians like Peter Schjeldahl to react with inebriated joy. Schjeldahl’s sine qua non is pleasure, the delirium of a sensuous high from which, later, language and its conceptual demands ensue. Still a poet at heart, Schjeldahl wants to fall in love and tell about it later in rapturous prose. And so Currin’s combination of art historical savvy (where Schjeldahl and frères can strut their stuff), painterly finesse, and subversive topicality adds up to a rave. Art critics of the world, unite!

It is, perhaps, the very materiality of Currin’s work, the fact that they are paintings, that most confuses the issue. If these were manipulated glossy prints or video investigations of identity (Cindy Sherman, Bruce Nauman) or narrative hybrids (William Kentridge), they would attract little attention, since Currin has no imaginative flair for either subjective introversion or cultural complexity, and he is no ironist. (He is sincere! He is ironic! He is sincerely ironic!) But compared to the peculiarly haunting and charged portraits of Gerhard Richter, another master of the lost art of painting, whose works engage us in a subtle and wily sensibility, steeped in multiple layers of (biographical, art historical, historical) narrative, Currin’s work is simplistic, repetitious, banal.

We have been taught to see through the subject, as if it were a mere transparent veil pulled across the glories of paint and its surfaces. This teaching begins the story of modernism, where the how always overrode the what; where form subsumes subject. When is a flag not a flag? When it is a picture by Jasper Johns. When is an apple not an apple? When it is in a painting by Paul Cézanne. Just remember: ceci n’est pas un pipe. Signifiers and signifieds, referents and signs. Along the way, the ‘subject’ disappeared entirely into the hallowed halls of abstraction and formalist critique, culminating in this country with, say, Brice Marden’s transcendental sublime, or Frank Stella’s grand coloured gears. Sooner or later, painting began to lose its edge, to falter before the hot new performative techno-installation-video-sound Matthew Barney/Damien Hirst extravaganzas. Of course painting went on, and painters like Leon Golub or Alex Katz or Amy Sillman or Frank Moore continued to find in the peopled and thingy world subjects for their work. Critics nattered about representation and narrative, but the hot spots were clearly over there, with Ann Hamilton’s poetics of architectonic scripture or Sarah Sze’s fantasy digs. If painting was alive and well, it had left these American shores and returned to its first home in retro-Europe, where people are still allowed to smoke.

If content inheres in the dissolution of subject and form, and if meaning is derived from our contemplation of this dissolution, what are we to make of John Currin’s effort so far? In Currin’s work, form and subject do not dissolve to release content; they remain obdurately separate, and we are forced to look through disparate lenses at the same time, distorting our vision. Asked to find meaning in the very cut that opens between these forms and these subjects, we cannot talk the formalist talk without falling on our faces in front of a frothy ‘heartless’ ingénue, a disastrous Thanksgiving. If you read the critics, none has found a way to speak about this work without separating, so to speak, the yolk from the white.

It has been a while since we were asked to address the full affective registers of visual art, to find ourselves reassessing our stake in its ability to interpret and illuminate, beyond the playground of lifestyles, hot tickets, and market allure. (I have been reminded, often, of another artist whose work caused similar outbursts of hyperbolic acclaim and derision, Julian Schnabel. Twenty years later, Schnabel is still a celebrity, but he dumped the art world for Hollywood’s greener pastures.) When I first saw Currin’s show, I gave it the most generous of interpretations, wanting to imagine Currin with a sympathetic gaze, depicting women, for example, as fashion victims, still beholden to outmoded cosmetic pressures and ideals. But the reading did not hold; it collapsed into wishful thinking. Currin pushes us away as he draws us toward, like a roadside crackup, or tabloid headline. He elicits our interest at the cost of our care. What if all he cares about is painting, if his subjects are only in service to a supreme indifference, verging on scorn? Are we complicit with this indifference, this contempt? Is every other, every alterity, merely a pretext for self-serving self-esteem? We are back, than, to modernist manners stripped of their consequence: James Joyce and T. S. Eliot, paring their fingernails, writing sonnets.

We pass the accident, glad that we are safe and sound in our SUV, just as targets are bombed from above, and the survivors left to their own blasted emergency.

So it might seem that this is Currin’s game: to marry high ‘European’-derived painterly technique and historical quotation to banal American illustrative pictorialism, and to let us, his viewers, suffer the indignities that result. No matter how much jargon of authenticity we muster in protest, the rich win at their own aura-denuded game, and the rest of us teach. Can we see through Cumin’s subjects to his ‘gorgeous’ surfaces, and ignore our desire to rescue them from a vindictive and puerile schoolboy stare, in thrall to butt and bust? Does Currin unsettle us, as Emerson would say, by placing us in an uncomfortable contradiction between masterly artifice and demeaning tableaux? That is, does he tell it like we are, trapped in a toxic homegrown brew of material-techno-plenitude of expertise-and-power, reality TV’s exploited and exploded private/public space, and the resulting damned fantasies of the ‘good life’.

We do not want to believe that someone as heralded as John Currin is a slick literalist of the imagination. A culture gets the artist, and the art, it deserves. The eagle soars over a destitute and cynical landscape.

Ann Lauterbach is an American poet, essayist, art critic and professor. She is old enough to be Currin’s mother.

Ann Lauterbach is an American poet, essayist, art critic and professor. She is old enough to be Currin’s mother.