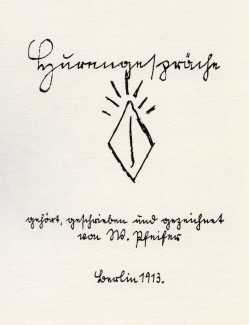

Heinrich Zille’s Hurengespräche (Whore Talk) cycle was published in 1921 (with the fictitious date 1913) as a private publication by the Fritz Gurlitt publishing house, under the pseudonym W. Pfeifer. It was banned by the official Berlin censors as soon as it appeared.

Heinrich Zille’s Hurengespräche (Whore Talk) cycle was published in 1921 (with the fictitious date 1913) as a private publication by the Fritz Gurlitt publishing house, under the pseudonym W. Pfeifer. It was banned by the official Berlin censors as soon as it appeared.

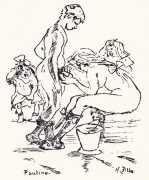

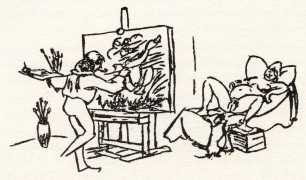

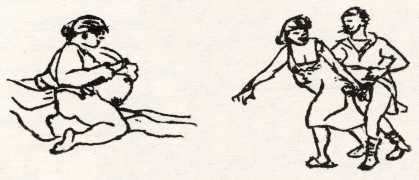

The cycle is about eight women who, gathered at an imaginary regulars’ table in a soup kitchen, exchange their experiences in Berlin’s ‘Milljöh’ at the beginning of the last century. The names of the women are just their first names or their nicknames, what the women call themselves – Olga, Pauline, Rosa, Alma, Pinselfrieda, Bollenguste, Lutschliese and Minna. Their accounts are all strongly sexual, influenced by the catastrophic living and living conditions in the working class of the time. The dialogues in the original tone and spoken in the Berlin dialect are probably reproduced authentically, and the illustrations interwoven with the text are strongly influenced by the reality prevailing at the time in which Zille was working. With merciless attention to detail, Zille depicts the pregnancy of a little girl by her own father while her mother is dying in the next bed, and the rape of another prostitute by a tramp.

The women call themselves whores, but all of them have other jobs such as flower women or factory workers. They describe their experiences, from early sexual abuse to tolerated incest, in unsentimental language. What they all have in common is that they strive for a different life, but in this life, because of their social circumstances and lack of opportunity for advancement or education as women, they have little choice other than to be whores and mothers. As Alma explains, ‘If we hadn't lived so dirty and we weren't so poor, then we'd want to do things differently.’

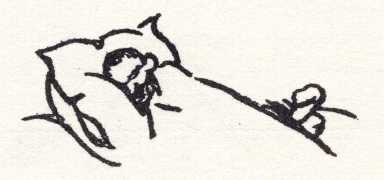

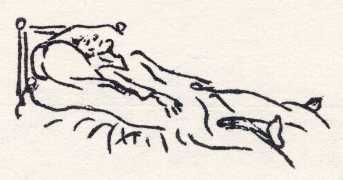

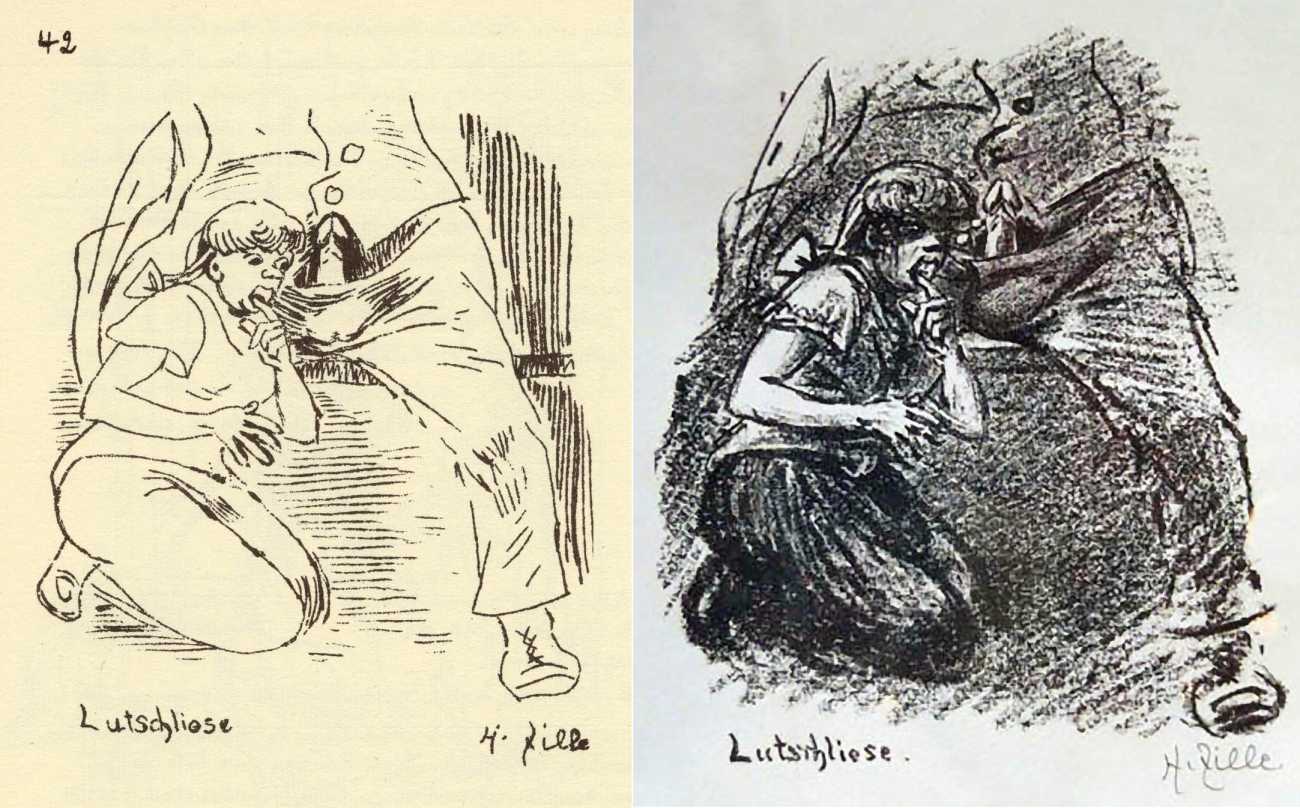

The drawings we show here are the complete original versions from the 1921 edition, but for many of these drawings, especially the larger full-page ones, several versions are known to exist. The dating of these alternative versions – nearly always much more detailed, usually shaded, and sometimes in colour – is unclear, but it is likely that after the initial publication of Hurengespräche, and especially after it was banned, there was a ready market for separate prints of the illustrations. It is sometimes thought that the quick, relatively crude, versions are not as good or as valuable as the more detailed equivalents; it is all a matter of personal taste.

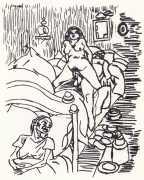

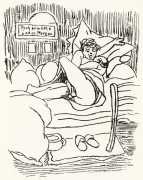

Here are a couple of examples. First, page 16 with the image of Alma with a client under the framed ironic epigram ‘Froh erwache jeden Morgen’ (Wake up happy every morning). The three versions are the original from the book, a more detailed shaded version, and a brightly-coloured one:

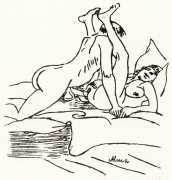

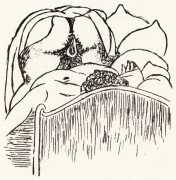

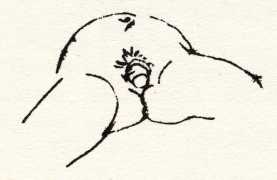

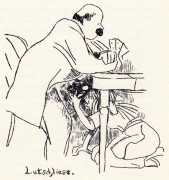

and second, page 42, Lutschliese wondering what a client is asking for, in the original from the book and as a more finished version:

and second, page 42, Lutschliese wondering what a client is asking for, in the original from the book and as a more finished version:

At least three other versions of this image are known.

At least three other versions of this image are known.

It is entirely possible, given the notoriety of Hurengespräche and Zille’s growing reputation, that some of these prints are opportunistic counterfeits.

The Gurlitt edition of Hurengespräche was published in a limited numbered edition of 100 copies, or which very few survive. A complete facsimile edition was produced by Schirmer & Mosel in 1979 in a limited edition of 1500 copies. There are numerous modern popular editions of the text (though sadly only in German), some of which include illustrations.