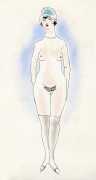

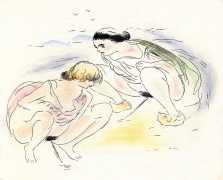

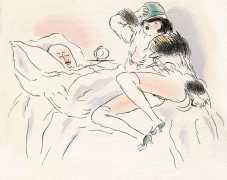

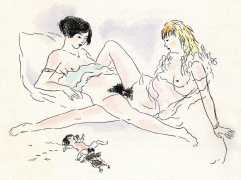

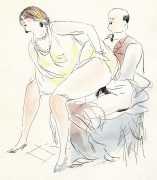

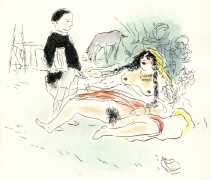

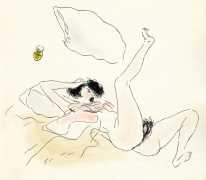

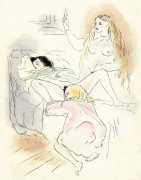

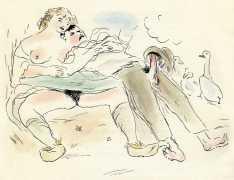

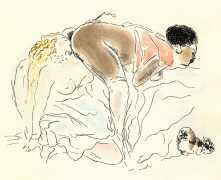

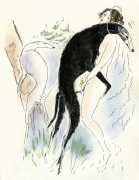

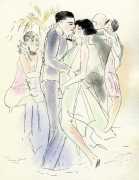

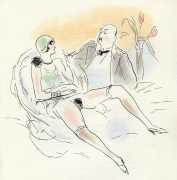

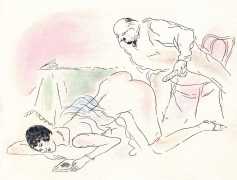

The Vertès illustrations for Pierre Louÿs’ Pybrac include images which, in the overused phrase beloved of broadcasters, ‘some viewers may find disturbing’; if you have found your way here, however, you will probably be as amused and intelligently provoked by them as author and illustrator intended. They do include subjects including juvenile sexual exploration and bestiality, so if you choose not to explore further press the ‘back’ button now. You have been warned …

Over the years Marcel Vertès illustrated nearly all of Pierre Louÿs’ published works, including both the bestselling Les aventures du Roi Pausole, La femme et le pantin (Woman and Puppet) and Poésies érotiques, as well as the lesser-known and more explicit texts including Pybrac, Manuel de civilité pour les petites filles (The Young Girl’s Handbook of Good Manners), and Trois filles de leur mère (Three Daughters and Their Mother).

Of these, Pybrac is probably the most outrageous set of illustrations Vertès produced, at least in a published volume; as Geoffrey Longnecker writes in his introduction to his English translation, there is little question that Pybrac is one of the filthiest books of poetry ever published, and there is equally little doubt that – to anyone interested in gradations of ‘filth’ – the Vertès illustrations are a perfect match with Louÿs’ fertile imagination.

Of these, Pybrac is probably the most outrageous set of illustrations Vertès produced, at least in a published volume; as Geoffrey Longnecker writes in his introduction to his English translation, there is little question that Pybrac is one of the filthiest books of poetry ever published, and there is equally little doubt that – to anyone interested in gradations of ‘filth’ – the Vertès illustrations are a perfect match with Louÿs’ fertile imagination.

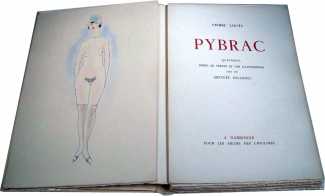

The Louÿs-illustrated edition of Pybrac was published ‘Pour les Soeurs des Ursulines, à Narbonne’ (For the Ursuline Sisters in Narbonne – a tongue-in-cheek reference to the Catholic sisterhood whose patron saint is St Ursula and whose mission is the education of girls and the care of the sick and needy). The numbered limited edition of 251 copies included six specials with an extra suite of illustrations.

In 2014 Wakefield Press issued a complete English translation (alongside the French originals) of the 313 quatrains of Pybrac, which includes a fascinating introduction by the translator, Geoffrey Longnecker. We have reproduced that introduction below, together with the first few verses, in both French and English, in the hope that if you are intrigued enough you will immediately rush to buy the book. The Wakefield Press Pybrac is illustrated with black and white versions of Toyen’s illustrations for Pybrac; you can see the complete colour versions here. Geoffrey Longnecker has also translated Louÿs’ The Young Girl’s Handbook of Good Manners and Charles Fourier’s The Hierarchies of Cuckoldry and Bankruptcy for Wakefield.

In 2014 Wakefield Press issued a complete English translation (alongside the French originals) of the 313 quatrains of Pybrac, which includes a fascinating introduction by the translator, Geoffrey Longnecker. We have reproduced that introduction below, together with the first few verses, in both French and English, in the hope that if you are intrigued enough you will immediately rush to buy the book. The Wakefield Press Pybrac is illustrated with black and white versions of Toyen’s illustrations for Pybrac; you can see the complete colour versions here. Geoffrey Longnecker has also translated Louÿs’ The Young Girl’s Handbook of Good Manners and Charles Fourier’s The Hierarchies of Cuckoldry and Bankruptcy for Wakefield.

TRANSLATOR’S INTRODUCTION

One of the better-known definitions of pornography remains that of Supreme Justice Potter Stewart, from the 1964 case Jacobellis v. Ohio: ‘I know it when I see it’. To echo Bishop Berkeley’s proposition regarding the falling tree in the forest, though, what happens to this definition when the subject matter in question is not seen?

Even the briefest of glances at Pybrac will make it apparent that there were many, many things that Pierre Louÿs did not like to see – a prudishly squeamish framework to these quatrains that, however ironic, provides an argument against their constituting pornography (or so, I imagine, the publisher hopes). Be that as it may, there is little question that Pybrac is one of the filthiest books of poetry ever published.

Like the rest of Pierre Louÿs’ voluminous output of erotica, Pybrac was not published during his lifetime, but instead figured among the many secret manuscripts discovered after his death, tucked and filed away, and subsequently auctioned off and scattered among collectors. It would see its first clandestine publication in 1927 (in an edition of 105 copies), two years after the author’s death.

In his excellent introduction to the most recent volume of Louÿs’ erotic writings (a volume that grows with every iteration as more manuscripts are discovered), Jean-Paul Goujon highlights a once obvious fact that can easily get overlooked today: Louis was considered an author of erotica during his lifetime, long before his secret literary production was discovered. The Surrealist Robert Desnos, for example, in his 1923 essay on eroticism written at the behest of French fashion designer Jacques Doucet, had no compunction in including Louis among his authors of note, solely on the basis of such books as Aphrodite and The Songs of Bilitis. Which is to say, unlike many French authors of his time, Louÿs’ secret output of erotica was not a break from his ‘over-the-counter’ writing (as in the case of such other contemporaries and authors of erotica as Guillaume Apollinaire or Pierre Mac Orlan), but an extension of it – and an extension that coincided with his writing career from its earliest stages.

From at least the age of eighteen, and over a period of three decades, Louÿs’ production of erotica was consistent and incessant – an engagement in writing that finds a loud echo in the very consistent and incessant Pybrac (in which an implicit endlessness overtakes and eventually trumps the humour at the origin of these rhymes), but also in the genre of erotica as a whole. The sense of a never-ending, heightened level of sexual ecstasy endemic to all erotica – and the implicit (if illusory) futility of the attempt at exhausting such imagined sexual ecstasy through every conceivable permutation, variation, duplication, and repetition of bodily organs and couplings – laces throughout the almost maniacal literary exercise of Pybrac, where one quatrain follows another into what threatens to become a hypnotic, maniacal descent into the infinite. Almost every conceivable form of sexuality is represented at least once throughout these rhymes: Louis's pet predilections for sapphism, sodomy, incest, and prostitution find ample representation here, as do the typical scenarios involving fellatio, cunnilingus, masturbation and exhibitionism. But we also have, to varying degrees, pedophilia, analingus, urolagnia, bestiality, sadomasochism, sacrilege, coprophilia, and such less common – and darker – territories as necrophilia, rape, castration, emetophilia, heterophilia, maschalagnia, mucophilia and piquerism. If there is anything missing from these 313 quatrains (voyeurism being one common -ism that seems to be absent, along with transsexualism and gerontophilia), it seems safe to say that it undoubtedly found representation among the many poems missing from this collection. For if the poems contained in this volume constitute Pybrac as the book is known today, these 313 quatrains actually represent only a fraction of the original collection: according to Goujon, over two thousand more quatrains remain unpublished and probably unknown to but a few collectors, with all trace of them lost since they were sold at auction in 1936.

The title that groups together this open-ended assemblage will have little resonance for the English reader, but at this point in literary history it probably has little for the French reader as well. It is derived from the name of Guy Du Faur, Seigneur de Pibrac (1529–1584), a French jurist, poet, and chancellor to Marguerite of France, Queen of Navarre, who notoriously rejected his attempts at wooing her. That fact, combined with Pibrac’s reportedly upright character (Montaigne said of him, on his death: ‘Good Monsieur de Pibrac, whom we have just lost, such a noble mind, such sound opinions, such a gentle character!’), undoubtedly contributed to Louÿs’ decision to employ a deformation of his name as the title to this collection. The mockery extends to the format and tenor of the poems, though, as Pibrac is best remembered for his own collection of poems (even if they have since fallen into obscurity): a set of 126 moralistic quatrains (decasyllabic, in contrast to Louÿs’ alexandrines), which throughout its endless printings bestowed good advice and guidelines to proper conduct upon many generations of French youth up until the nineteenth century. The spirit of Pibrac’s quatrains can be easily assessed from the one that opens his collection:

By God, then Father & Mother abide:

Be just and true: & in ev’ry season

Show the innocent the path to reason:

From God’s judgment on high you cannot hide.

Through its implicit mockery of Pibrac’s moral instruction and his failure at amorous seduction, Pybrac shares the same spirit of other parodic works by Louÿs, such as his Young Girl’s Handbook of Good Manners for Use in Educational Establishments. Much of the book’s humor lies in its juxtaposition of a controlled set of crude vocabulary, proper literary style (the formal a b a b rhyming alexandrine quatrain), and ironic moral outrage. Maintaining all three of these components was this translator's priority.

Regarding the vocabulary, Louÿs rarely utilises slang in Pybrac, and the vulgar words he does employ tend to be standard ones (‘con’, ‘pine’, ‘foutre’, ‘vit’, etc). Though drawing on the elasticity of sexual euphemism would have been welcome on more than one occasion in working out the English rhymes for this volume, doing so would have gone against the grain of the (relative) ‘purity’ of Louys's style: even at his most crude and vulgar, Louÿs always maintained a literary elegance.

Regarding the literary style of Pybrac, the alexandrine is a classic form of verse in French poetry, although it is one rarely used in English (or at least not since before the time of Shakespeare). Rendering this form into iambic pentameter has long been somewhat standard for English translation. I have made an attempt at maintaining the twelve-syllable line in these translations, however (as well as at keeping the caesura between the sixth and seventh syllables, which allows a proper alexandrine to break easily into two halves): apart from the flexibility those two extra syllables can give in carrying a verse over into English, I will confess to a predilection for maintaining an element of the ‘foreign’ in the translation process. This book is a dual-language edition, in any case, so dissatisfied readers may turn to the French.

Finally, regarding the sense of moral outrage, the reader may rest assured that in translating Pybrac, this translator’s moral sensibilities were as outraged as the reader's will be upon reading it.

Attempted fidelity, then; maintaining these three qualities did sometimes require taking some slight liberties with the text (though if there was ever a text with which to ‘take liberties’, Pybrac makes for an appropriate candidate); but to maintain strict fidelity to the content of Louÿs’ quatrains at the cost of their form would generally miss the point of these poems. Content has been occasionally tweaked for the sake of a rhyme or syllabification: a past tense is sometimes rendered in the present, genitals may take on an extra lubricity not detailed in the French, a generic fish may turn into a more specific sturgeon (to rhyme, as the reader may already suspect, with ‘virgin’), etc. If complaint is to be made, though, it will more likely be over some of the rhymes: English does not offer the same range of possibilities as the French, and though I may have at times patted myself on the back over some of the rhymes (or near-rhymes) I employed (‘manure’/‘amour’, ‘serenade’/‘tribade’, ‘duchess’/‘clutches’), there are others I admittedly turned to more than once (‘cuckold’/‘butthole’, ‘mother’/‘laver’, and the perhaps too easy coupling of ‘lass’/‘ass’). Some repetition is simply carried over from the French text, though: the wealth of apprentices and dancers throughout, for instance, merely reflects Louÿs’ frequent recourse to ‘arpètes’ and ‘danseuses’.

But I will stop there: to engage in a defense of Pybrac or its translation is something that would turn into a truly perverse endeavor. Louÿs spent a good part of his life, from the age of eighteen on, writing texts like this for an audience of one (save in his more malicious moments, when he’d attribute them to other authors, such as his former friend, André Gide), and in all honesty, this translation had originally been undertaken as a private solo effort at shirking some more mature responsibilities in my own life. Undoubtedly, a number of people would prefer that the audience for these translations had remained a body of one; I can only imagine that they are not likely to be reading this, though. But to all devotees (of age eighteen and on) of reading and writing – solitary pleasures – who don’t look on humor as a sine qua non, let it simply be said, in musical measures: I do not like to see translators who waste time on readers who don’t feel that all is permitted, hammering out verses in fornicating rhyme: poetry is guilty and needs to admit it.

FRENCH TEXTS

Je n’aime pas qu’Agnès prenne pour concubine

Sa bonne aux cheveux noirs, gougnotte s’il en fut,

Qui lui plante sa langue au cul comme une pine

Et qui lui frotte au nez son derrière touffu.

Je n’aime pas à voir qu'en l'église Saint-Supe

Une pucelle ardente, aux yeux évanouis,

Confessant des horreurs, se branle sous sa jupe

Et murmure: ‘pardon ... mon Père ... je jouis’.

Je n’aime pas à voir la nouvelle tenue

De la jeune lady qui vient au bal masqué

Une cuisse en culotte et l’autre toute nue

Jusqu’au milieu du con, Madame, c’est risqué.

Je n’aime pas à voir l’Andalouse en levrette

Ouvrir les bords poilus de son cul moricaud

Qui porte à chaque fesse une sorte d’aigrette

Sur l’anus élargi comme un coquelicot.

ENGLISH TEXTS

I do not like it that Agnès’s latest trick,

Her black-haired maid, a lez from her head to her toes,

Plants her tongue in her cunt as if it were a prick

And rubs her hairy bum with the tip of her nose.

I do not like to see at the Saint-Sulpice church

An ardent young virgin with her senses humming

Confess her dreadful deeds, jerk off under her skirt,

Murmuring: ‘forgive me ... my Father ... I’m coming’.

I do not like to see the brand new eveningwear

Of the lady who comes to the ball to sashay

With one thigh in panties and the other all bare

Straight on up to the cunt, dear lady, it’s risqué.

I do not like to see the dark Andalusian

On her knees spread her ass, all hairy and soppy,

Bearing on each buttock a feathered protrusion

Framing an anus as stretched-out as a poppy.