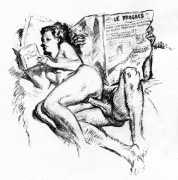

Trente et quelques attitudes (Thirty-something Positions), published without any indication of date or place of publication around 1952, tells us only that it contains original lithographs by ‘Jean de l’Etang’. In French an étang is a small pond, so in this anthology of drawings and texts on the theme of erotic encounters we see Jean ‘du lac – of the lake of artistic endeavour’ Dulac in the more intimate role of Jean ‘de l’étang – of the pond of intimate sensuality’ de l’Etang. A substantial publication, the boxed portfolio contains 25 full-page pencil drawings on separate sheets and 28 smaller pen and ink sketches interspersed with quotations from poets and writers. The typography is typically French mid-century, and the production, while entirely competent, has the feel of being provincial rather than Parisian mainstream; the whole project was probably managed by its author using a local Lyonnaise printer.

Trente et quelques attitudes (Thirty-something Positions), published without any indication of date or place of publication around 1952, tells us only that it contains original lithographs by ‘Jean de l’Etang’. In French an étang is a small pond, so in this anthology of drawings and texts on the theme of erotic encounters we see Jean ‘du lac – of the lake of artistic endeavour’ Dulac in the more intimate role of Jean ‘de l’étang – of the pond of intimate sensuality’ de l’Etang. A substantial publication, the boxed portfolio contains 25 full-page pencil drawings on separate sheets and 28 smaller pen and ink sketches interspersed with quotations from poets and writers. The typography is typically French mid-century, and the production, while entirely competent, has the feel of being provincial rather than Parisian mainstream; the whole project was probably managed by its author using a local Lyonnaise printer.

WhenTrente et quelques attitudes appeared, Jean was very much in love with his second wife Lucienne Collaud, and it is easy to see the link between the sensual satisfaction he found in their relationship and the artwork in this wonderful portfolio; she was undoubtedly one of the models for it.

The large drawings show Dulac as a supreme observer of the human body and its contours; the smaller sketches add a quick-eyed humour and vitality. Even the paper covers wrapped around the portfolio contents display the artist’s appreciation of matching structure to content, with their minimalist pencil interpretations of the front and back of a female torso.

The large drawings show Dulac as a supreme observer of the human body and its contours; the smaller sketches add a quick-eyed humour and vitality. Even the paper covers wrapped around the portfolio contents display the artist’s appreciation of matching structure to content, with their minimalist pencil interpretations of the front and back of a female torso.

Most of the words in the portfolio are quotations from other authors, but the introduction is by Jean himself. He writes:

My aim here is to review the variety of erotic encounters; not all of them, in truth, how would it be possible to enumerate the thousand inventions, the thousand positions, that together combine in the ingenious satiety of pleasure? But there are those which lend themselves more easily to a methodic classification. Do not expect, curious reader, to feast your imagination on a greater hope than this.

I am not a man who seeks glory by revealing the results of personal experiments or novel attempts to achieve notoriety. I did not seek to make it my apprenticeship; I do not wish to set an example. We already have Astyanassa (in mythology, Helen of Troy’s maid) who, according to Suidas (the Byzantine encyclopedist), was the first to speak of the variety of erotic positions. Then there was Philaenis of Samos (a fourth century courtesan); she also preceded me. Then there was that divine genius Lorenzo Veniero, a noble Venetian, the author of a pamphlet La puttana errante (The Wandering Whore), in which he took upon himself to enumerate up to thirty-five ways of making love. Then there was Nicolas Chorier, a French lawyer, who under the name of Luisa Sigea, a young Spanish woman, wrote of the arcana of love and of Venus. And how many more encores have there been?

I regret that time has destroyed the works of my predecessors, the ancient teachers I have just quoted. Yet they have not lacked studious readers and attentive listeners, and I trust that neither readers nor listeners will be lacking for my book.

I drew it, quite indifferent to fame, for those who do not go hunting nature with pitchforks, for those who have the courage to live, who do not want to conceal themselves in the darkness, who want to appear brazenly in the open, who think, in short, of the things of love.

As in all things, the best approach is to enjoy an honest mediocrity; let others claim for themselves the appellation of being wise.

Trente et quelques attitudes was produced in a boxed numbered limited edition of 200 copies, of which thirty included an original drawing.