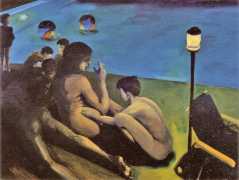

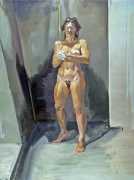

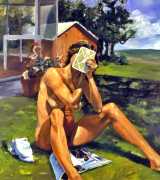

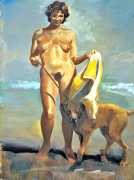

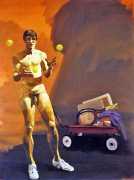

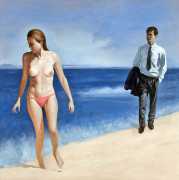

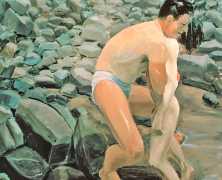

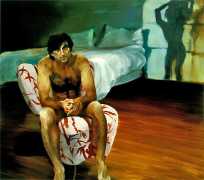

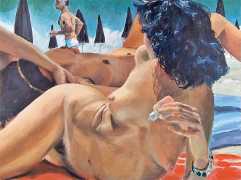

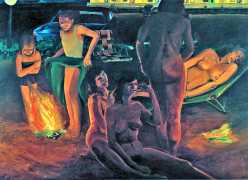

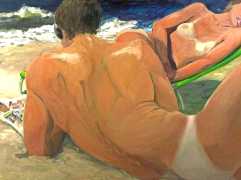

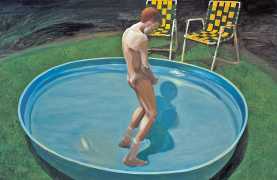

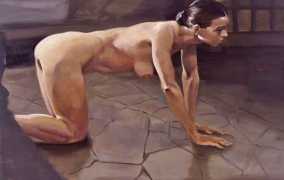

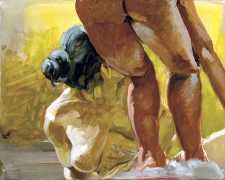

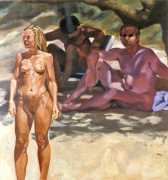

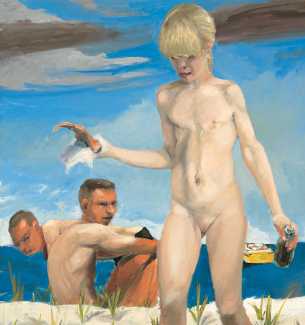

Eric Fischl became famous in the eighties for his scenes from suburban life on Long Island. In ‘Sleepwalker’ a sullen adolescent masturbates into the children’s paddling pool, while in ‘Bad Boy’ his cousin sneaks a glimpse of a woman’s naked pudenda while groping for money in her open bag. She might be his mother, his sister, his neighbour – this is John Updike with an incestuous twist. Fischl also probed deep into thirties realism, discovering spurts of sexual anxiety among the angled shadows.

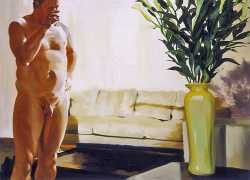

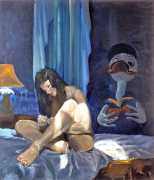

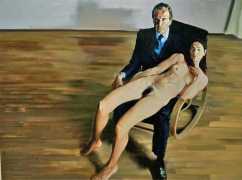

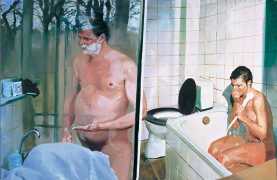

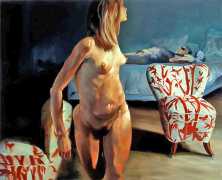

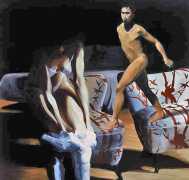

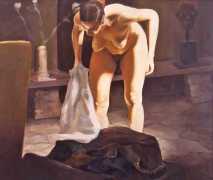

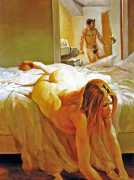

Not everyone finds Fischl’s art original and inspiring. Here is Laura Cumming reviewing a 2000 exhibition featuring his large ‘The Bed, The Chair, The Sitter’ series:

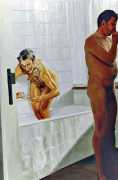

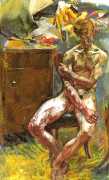

‘Twenty years and much celebrity later, Fischl is showing a series of oils and some giant watercolours in the Gagosian Gallery in London. The oil paintings form a freeze-frame sequence, enacted in a single bedroom and featuring the same naked woman. There are continuity faults – nightstands vanish, telephones appear – to establish a specious air of uncertainty. Everything strains for portentous effect, an effect scuppered by Fischl’s lack of skill as an artist. Where he can’t bring off an arm or a leg, he tries to achieve it by slithering incoherently all over the canvas. He uses paint like greasy lubricant. For a figure painter his anatomy is amazingly inept. By his own humble admission Fischl has never mastered even the rudiments of draughtsmanship. Which doesn’t leave much but content and a starry reputation.’

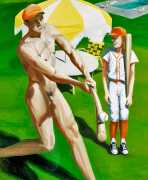

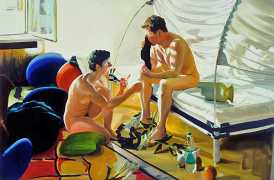

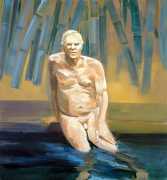

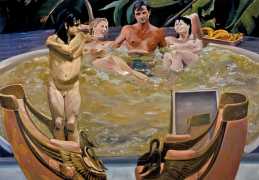

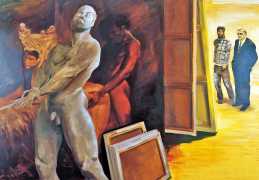

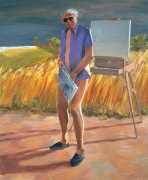

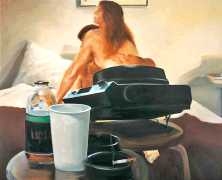

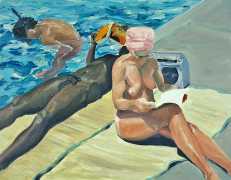

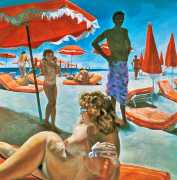

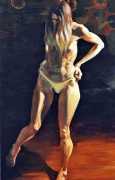

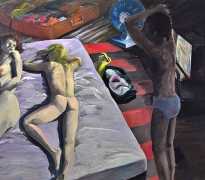

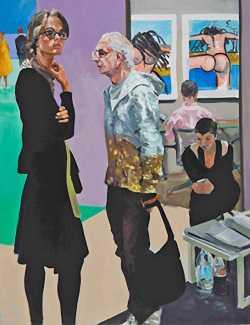

Fischl’s more recent work continues the themes of social alienation and the relationship between the artist and the everyday world. For example, in 2013, having been invited to an art fair to give a talk, he was appalled and fascinated by the attendees and their responses (or lack thereof) to the art on view. He then visited a few more art fairs with his digital camera in hand, later collaging images from these photographs together in Photoshop and using them as the basis for this series of large-scale paintings. One of these is the 2015 painting ‘What Doesn’t Go Away’, which shows gallerists and fairgoers set against a backdrop consisting of two images of Carol Dunham’s lusty, exuberantly sexual, in-your-face female nudes. All manage to ignore the Dunhams, including the man in the pink shirt in whose face the images appear. In the left foreground, a woman, who is as shielded by her black clothing as Dunham’s figures are exposed in their nudity, stands in a self-protective gesture, looking out of the painting and away from the speaking man standing before her.

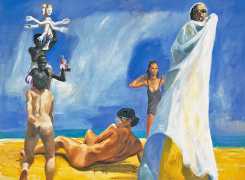

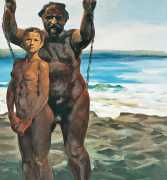

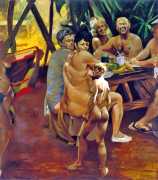

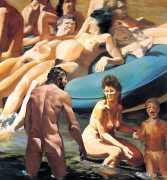

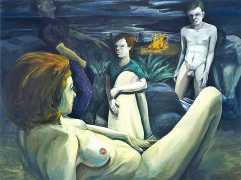

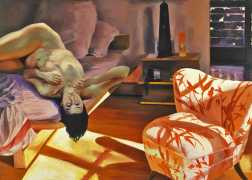

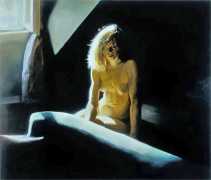

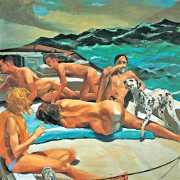

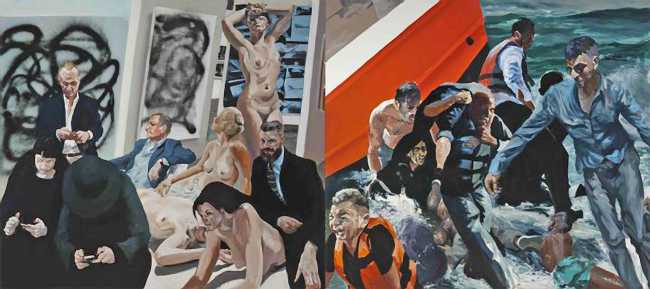

The 2016 painting ‘Rift Raff’ takes the same theme into the socio-political arena. The right-hand panel offers a scene of turmoil – asylum-seeking refugees, among them an old woman and a young boy, struggling in the water, being giving assistance and carried to safety. In contrast the left-hand panel presents a tableau from an art fair, with four naked women intermingling with five resting fairgoers. None of the figures on the left-hand panel are aware of the chaos taking place to the right, some on their cellphones while others stare into space. One of the women turns her head to look at what appears to be an abstract painting by Christopher Wool, another, her arms raised to her forehead, looks out of the painting to the viewer with what appears to be a troubled and critical gaze.