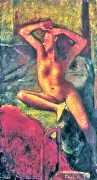

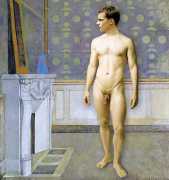

Balthus’s artistic style is primarily classical, the influences on his work including the writings of Emily Brontë, the writings and photography of Lewis Carroll, and the paintings of Masaccio, Piero della Francesca, Simone Martini, Nicolas Poussin, Jean-Étienne Liotard, Joseph Reinhart, Théodore Géricault, Jean Ingres, Francisco Goya, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Gustave Courbet, Edgar Degas, Félix Vallotton and Paul Cézanne. Although his technique and compositions were often inspired by pre-renaissance painters, there also are eerie intimations of contemporary surrealists like Giorgio de Chirico. Painting the human figure at a time when figurative art was largely ignored, he is widely recognised as a significant and influential twentieth-century artist.

Fellow artist Antonin Artaud wrote about Balthus’s paintings that ‘Balthus paints, primarily, light and form. By the light of a wall, a polished floor, a chair, or an epidermis he invites us to enter into the mystery of a human body. That body has a sex, and that sex makes itself clear to us, with all the asperities that go with it. The nude I have in mind has something harsh about it, something tough, something unyielding, and – there is no gainsaying the fact – something cruel. It is an invitation to lovemaking, but one that does not dissimulate the dangers involved.’

Until the end of his artistic life, Balthus claimed that he needed total quiet to work, because painting was like prayer for him. He wrote ‘One should die amid the sweet promise of meeting god, in the splendour of which, I’m convinced, painting has always sought to pave the way.’

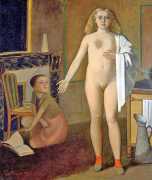

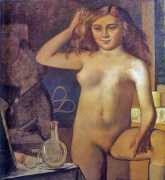

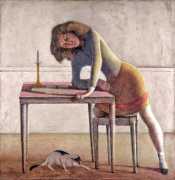

Many of Balthus’s paintings depict young girls, either naked or nearly so. Balthus always insisted that his work was not erotic, but that it recognised the discomforting facts of children’s sexuality. In 2013 Balthus’s paintings of adolescent girls were described by Roberta Smith in The New York Times as ‘both alluring and disturbing’. Balthus emphasised that his art was about innocence, and referred to the young girls he painted as ‘angelic’. In 1985 his painting Girl and Cat was used as the cover illustration for Penguin edition of Vladimir Nabokov’s novel Lolita, to which Balthus commented ‘I really don’t understand why people see my paintings of girls as Lolitas. You know why I paint little girls? Little girls are the only creatures today who can be pure and timeless. Some American journalist said he found my work pornographic. What does he mean? Most advertising with female models is more pornographic.’

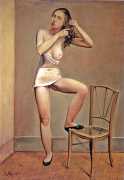

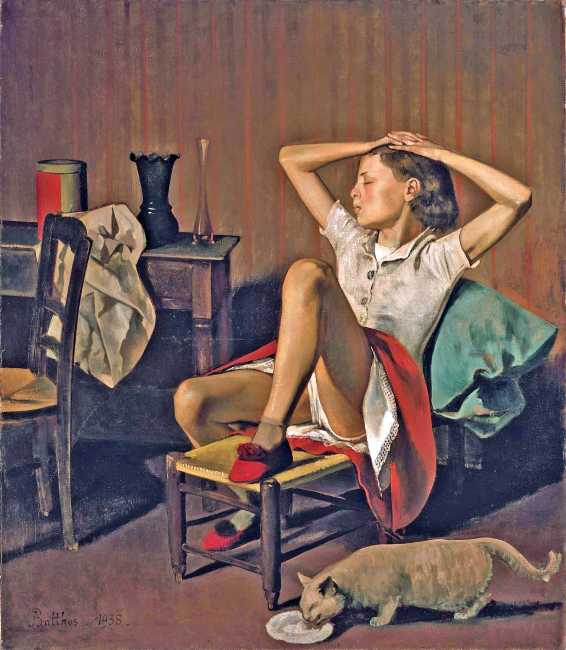

The first series of paintings he made was of a young girl named Thérèse Blanchard, a neighbour of Balthus in his atelier at the Cour de Rohan, near the place de L’Odeon in Paris. Balthus made ten paintings of Thérèse Blanchard, capturing the vulnerability and spirit of a girl on the threshold of adolescence. In Girl and Cat (Fille et chat) Thérèse appears self-absorbed, aloof or dreaming, with the cat as her sole companion and playmate. The Thérèse paintings remain some of his most widely recognised.

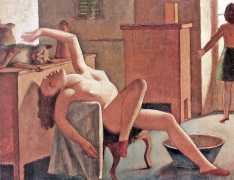

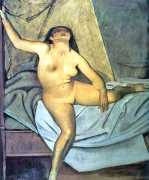

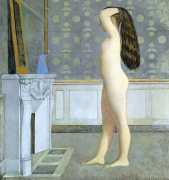

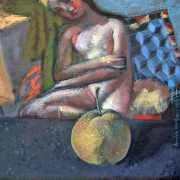

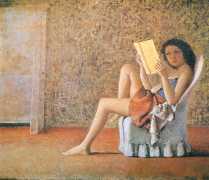

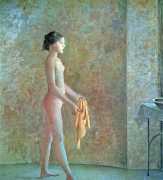

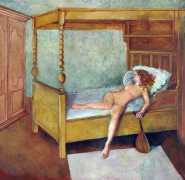

The paintings here are shown in date order, starting with an early nude from 1925, and ending with Young Girl with Mandolin (La jeune fille à la mandolin) of 2000.

Two of Balthus’s paintings in particular have regularly been singled out as ‘problematic’, The Guitar Lesson (La leçon de guitar) from 1934, and Thérèse Dreaming (Thérèse rêvant) from 1938.

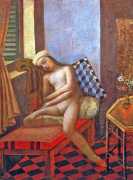

The Guitar Lesson (La leçon de guitar) is among the most notorious yet least discussed by Balthus’s contemporary critics. No music is being played in the scene depicted, as the tutorial has turned instead into what appears to be a sexual initiation rite. The composition is considered by some critics as being based on a Pieta, probably the Louvre’s mid-fifteenth-century Pieta of Villeneuve-les-Avignon, to judge from the near identical height and comparable sizes of the figures. In The Guitar Lesson, Balthus depicts a female music teacher holding a young girl across her thighs in lieu of the toy-like musical instrument abandoned on the floor.

The Guitar Lesson (La leçon de guitar) is among the most notorious yet least discussed by Balthus’s contemporary critics. No music is being played in the scene depicted, as the tutorial has turned instead into what appears to be a sexual initiation rite. The composition is considered by some critics as being based on a Pieta, probably the Louvre’s mid-fifteenth-century Pieta of Villeneuve-les-Avignon, to judge from the near identical height and comparable sizes of the figures. In The Guitar Lesson, Balthus depicts a female music teacher holding a young girl across her thighs in lieu of the toy-like musical instrument abandoned on the floor.

The child makes no attempt to struggle. Her body is arching and her posture evokes the scene of the lap of the Virgin Mary depicted in the Pieta. Her female teacher’s hands are positioned on the girl as for playing the guitar, one near her inner leg and another holding the young girl’s hair. Depicting as it does the body of a young girl, the painting is particularly controversial, as some see an appalling scene of sexual violence while others admire the beauty of the composition, with its depiction of youthful eroticism. There is no immediate suggestion of violence, they point out, the delicacy and position of the figures implying nothing beyond an innocent game.

The history of The Guitar Lesson is as interesting as its subject matter. During the two-week 1943 exhibition at the Galerie Pierre, The Guitar Lesson hung in the gallery’s back room, accessible only to a select few. It was only displayed in private for fifteen days. In 1938 the painting was purchased by the art collector James Thrall Soby, who had intended on displaying it, but after the museum opted to keep the painting in its vaults rather than on display due to its controversial nature, Soby decided to sell the painting.

Soby exchanged the painting with the Chilean artist Roberto Matta Echaurren in 1945; however, Echaurren’s wife later left him and married Pierre Matisse, the youngest son of Henri Matisse, who owned a gallery in New York, where the painting remained in the vaults until 1977.

In 1977 the Pierre Matisse gallery displayed the painting for a month, which caused a huge media sensation, several influential critics suggesting that the work was too shocking to be shown. After the Matisse gallery exhibition the painting was donated to the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where it was accepted, but kept in the museum’s vaults. It was shown in a private exhibition in 1982, and again provoked some shocking reactions, including from Blanchette Rockefeller, who was so appalled by the painting that she insisted that MOMA sold it. The painting was sold again several times, ending up with a Greek collector.

This beautiful yet controversial painting has been exhibited only twice for a very short time and in private presentations, yet with easy access to it on the internet it still splits audience opinion, responses ranging from shock and outrage to more thoughtful and considered opinions, but always making the viewer think about their response to it.

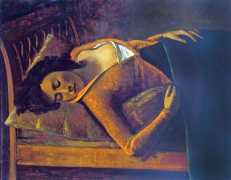

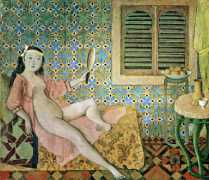

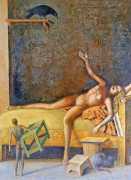

In 2017 the 1938 Balthus painting Thérèse Dreaming (Thérèse rêvant) became the subject of a petition started by a feminist activist demanding the Metropolitan Museum in New York, who owns the painting, remove it from display. The petition argued that ‘The artist of this painting, Balthus, had a noted infatuation with pubescent girls, and this painting is undeniably romanticising the sexualisation of a child. Given the current climate around sexual assault and allegations that become more public each day, in showcasing this work for the masses the museum is romanticising voyeurism and the objectification of children.’ The petition gathered almost 9,000 signatories.

In 2017 the 1938 Balthus painting Thérèse Dreaming (Thérèse rêvant) became the subject of a petition started by a feminist activist demanding the Metropolitan Museum in New York, who owns the painting, remove it from display. The petition argued that ‘The artist of this painting, Balthus, had a noted infatuation with pubescent girls, and this painting is undeniably romanticising the sexualisation of a child. Given the current climate around sexual assault and allegations that become more public each day, in showcasing this work for the masses the museum is romanticising voyeurism and the objectification of children.’ The petition gathered almost 9,000 signatories.

The painting depicts Balthus’s favourite model and neighbour Thérèse Blanchard, reclining in a chair in a carefree pose that leaves her underpants visible. Balthus and some of his supporters claimed that nothing in this painting suggest any pornographic or sexual context, only the natural subconscious pose of a young girl relaxing. Thérèse is presented lost in thought, sitting in a chair and relaxing, alone in a room with a cat. While the pose does reveal her underpants, there is no other indicator of any sexual context.

The Met decided not to remove the painting from display, and Kenneth Weinel, the museum’s Chief Communication Officer, issued a statement saying ‘Moments such as this provide an opportunity for discussion, and visual art is one of the most significant means we have for reflecting on both the past and the present, and encouraging the continuing evolution of existing culture through informed conversation and respect for creative expression.’