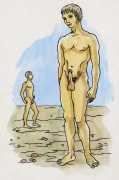

Of all the enfants terrible of French poetry, Arthur Rimbaud was arguably the most terrible, which probably went hand-in-hand with also being one of the most original and risk-taking. He took active delight in shocking; when he arrived in Paris in 1871 he moved into the Montmartre apartment where Paul Verlaine and his new wife Mathilde were lodging with her parents. He was an impossible guest. He took to nude sunbathing just outside the house. He turned his room into a squalid den. He mutilated an heirloom crucifix. He was proud of the lice infesting his long mane and even pretended he was encouraging the vermin to jump on to passers-by. Verlaine was delighted with Rimbaud’s antisocial antics, and introduced him to his friends in the cafés where they congregated regularly.

After the first encounter, one of Verlaine’s friends, Léon Valade, wrote the next day to an absent member, ‘You missed a great deal by not being there. A most daring poet not yet eighteen was introduced by Paul Verlaine, his inventor and in fact his John the Baptist. Big hands, big feet, a wholly babyish face like a child of thirteen, deep blue eyes! Such is this boy, whose character is more antisocial than timid and whose imagination combines great powers with unheard-of corruption and who has fascinated and terrified all our friends.’

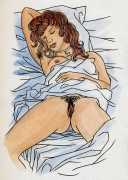

This volume illustrated by Elie Grekoff brings together poems from two of Rimbaud’s most ‘corruptive’ compilations, the homoerotic trilogy Les Stupra, and the parody collection Album dit Zutiques. Les Stupra (the word means ‘obscenity’) was published as a pamphlet published by Messein in 1923. No autograph manuscript is known, and the first two poems were reconstructed by Ernest Delahaye from memory before sharing them them with Verlaine in October 1883.

Album dit Zutiques was a collection of poems written by Paul Verlaine, Arthur Rimbaud and their friends, who used to met in a room of the third floor at Hotel des Étrangers on boulevard Saint-Michel. First known as the ‘villains bonhommes’, they were renamed the Cercle Zutique by Charles Cros. They spent much time parodying each other, preferably in an obscene way, an exercise Rimbaud was particularly good at. Each of these poems has two names attached; that of the poet being parodied and that of its author. The Album was first published in 1943.

Here is one of the Stupra poems as a taster, in the original French and in English translation …

Nos fesses ne sont pas les leurs. Souvent j’ai vu

Des gens déboutonnés derrière quelque haie,

Et, dans ces bains sans gêne où l’enfance s’égaie,

J’observais le plan et l’effet de notre cul.

Plus ferme, blême en bien des cas, il est pouvu

De méplats évidents que tapisse la claie

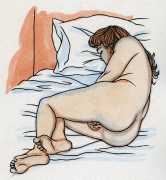

Des poils; pour elles, c’est seulement dans la raie

Charmante que fleurit le long satin touffu.

Une ingéniosité touchante et merveilleuse

Comme l’on ne voit qu’aux anges des saints tableaux

Imite la joue où le sourire se creuse.

Oh! de même être nus, chercher joie et repos,

Le front tourné vers sa portion glorieuse,

Et libres tous les deux murmurer des sanglots?

Our buttocks are not theirs. I have often seen

People unbuttoned behind some hedge,

And, as in those shameless baths where children are content,

I observe the forms and effects of the naked rear.

Firmer, in many cases pale, it possesses

Striking forms which the screen

Of hairs covers; for women, it is only in the charming parting

That the long tufted silk flowers.

A touching and marvellous ingenuity

Such as you see only in angels in holy pictures

Imitates the cheek where the smile makes a hollow.

Oh! For us to be naked like that, seeking joy and repose,

Facing our companion’s glorious parts,

Both of us free to murmur and to sob?

The Grekoff-illustrated Rimbaud was published in Paris with the imprint ‘A l’angelot maudit’ (The Cursed Angel), in a numbered limited edition of thirty copies.