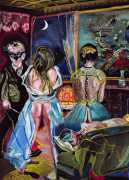

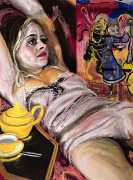

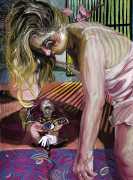

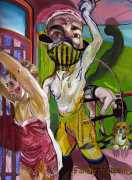

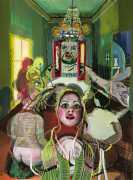

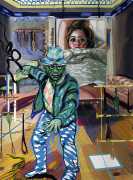

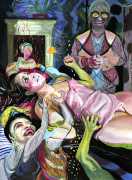

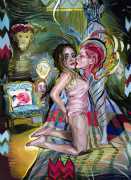

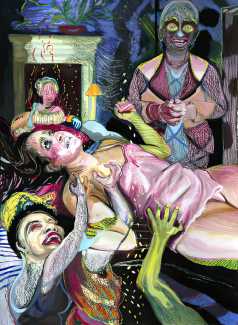

The Story of O is an erotic novel published in 1954 under the pseudonym Pauline Réage. Many assumed the book, which features multiple scenes of bondage, domination and sexual exploration, was written by a man, but in 1994 Dominique Aury came forward as the author. You can read more about how the author’s true identity was revealed here. The Story of O is still controversial, and it’s one that Natalie Frank rereads every year. After creating paintings and drawings for Grimms’ fairy tales, the artist decided she was ready to tackle this highly sexual narrative. The images she created for this series edge on the surreal, with exaggerated forms, lucid colours, and figures that bleed into patterned backgrounds. There are whips, erotic engagements, and the heroine O in many compromising positions.

In May 2018 the paintings were exhibited at the Half Gallery in New York, and Katy Donoghue from Whitewall Art interviewed Natalie Frank to find out more about the series, female desire, and her strong views on issues around sexism in the art world. You can read the interview online here.

What was your first interaction with The Story of O?

I found it in a bookstore. Women in Love was the first erotic book I read. The Story of O was the first erotic book I read written by a woman. I remember picking it up, vaguely knowing there was a backstory – that maybe there was some sort of scandal around it – which made it even more compelling to pick up and read. I remember buying it and reading it and carrying it various places. I was very aware to cover the cover so people couldn’t see what I was reading. It was kind of an inside, fun, secretive, and transgressive act.

What made you want make work about it?

There are two books I read every year, and The Story of O is one of them. My understanding of what is going on in the book, the relationships between the characters, has changed a lot since I first read it. For thirteen years now I’ve made work about women and their bodies and sexuality and power. The Story of O is like the apotheosis of this set of concerns. It was always something that I had in the back of my mind that I wanted to do something with. As I’ve started to work more with literature in the past few years – starting with the Grimm’s book and group of drawings – the idea that I could take this book and bring it to life through drawings came about. I knew I could do it, and it felt like that was the right medium for it.

Did you explore a new way of working with this series?

I think of this book and this body of work as a contemporary fairy tale for women. So the palette comes out of that. There are teals and reds and stripes; a lot going on, a lot of patterning and marks that become abstraction, but also helps with the movement of the composition. I’m curious how people will find it. The book was published and banned in the fifties and there have been so many readings of The Story of O. It’s kind of wonderful that art can be so provocative and cause so much contentious conversation, and I hope the drawings can do the same.

The scenes you’ve drawn are graphic, sure, but as you mentioned, brightly coloured with patterns. They don’t feel dark or aggressive to us, despite the whips.

I went back to Susan Sontag and The Pornographic Imagination and reread that essay; she uses The Story of O to talk about the difference in pornography and art. At the end of the day, no women were used in the making of these images; no women were harmed. This is art, it’s imagination, the character goes through transformation. The whole book focuses on her interior life, her physical transformations, her emotional transformations. There’s no doubt that it’s not pornography, though it plays with tropes of pornography. Sontag calls it meta-pornography. It takes a laugh at clichés of pornography, but it’s a very serious – to my mind – exploration of a woman’s growing sense of self. I think that’s why many look at it as an icon of sex-positive feminism. It’s a fantastic image of what we’re going through now.