The eighteenth-century writer and social commentator Nicolas-Edme Réstif (sometimes spelt Retif) was born at Sacy near Reims in north-east France, he was educated by the Jansenists at Bicêtre, but was involved in a sexual scandal and apprenticed as a printer at Auxerre. In 1760 he married Agnès Lebègue, a relative of his Auxerre teacher. Within a few years he was writing and printing his own books on a wide variety of subjects, and by his death he had produced some two hundred volumes, many of them printed by his own hand. He was a highly original thinker and a confirmed rebel, with fascinating ideas on a range of subjects from prostitution reform to communal living; he is thought to have been the first writer to use the word ‘communist’ in its modern meaning. He is particularly vivid in his descriptions of his early sexual awakening, women’s clothes and particularly their shoes being especially powerful, such that he is often cited as the first recorded shoe fetishist.

The eighteenth-century writer and social commentator Nicolas-Edme Réstif (sometimes spelt Retif) was born at Sacy near Reims in north-east France, he was educated by the Jansenists at Bicêtre, but was involved in a sexual scandal and apprenticed as a printer at Auxerre. In 1760 he married Agnès Lebègue, a relative of his Auxerre teacher. Within a few years he was writing and printing his own books on a wide variety of subjects, and by his death he had produced some two hundred volumes, many of them printed by his own hand. He was a highly original thinker and a confirmed rebel, with fascinating ideas on a range of subjects from prostitution reform to communal living; he is thought to have been the first writer to use the word ‘communist’ in its modern meaning. He is particularly vivid in his descriptions of his early sexual awakening, women’s clothes and particularly their shoes being especially powerful, such that he is often cited as the first recorded shoe fetishist.

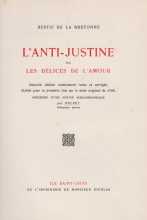

Rétif’s L’anti-Justine, ou les delices d’amour (Anti-Justine, or the Joys of Eros) was published in 1798 under the pen-name of Jean-Pierre Linguet. Sixty illustrations were announced on the title-page, but they never appeared. Of the eight parts that Rétif promised in the preface, only the first two were published. His justification for the volume, and for the title, was that de Sade’s best-known works, including Justine, had recently been published, and Rétif wanted to balance de Sade’s excessive sexual cruelty with a ‘more purely sexual’ alternative.

The anonymous accompanying illustrations to this edition, created in the 1930s in the style of the early nineteenth century, succeed in conveying the subject matter of the stories while maintaining the period feel of the narrative.

Here is Rétif’s preface to the first edition of L’anti-Justine, together with the beginning of the first chapter.

Preface

No-one has been more incensed than I by the foul performances of the infamous Marquis de Sade – I refer to his Justine, to Aline, to le Boudoir, la Théorie du Libertinage, which I read while languishing in prison. This villain never presents the delights of love experienced by men without accompanying them by torments and even death inflicted upon women.

My design is to write a book, sweeter to the taste than any of Sade’s, and which wives who would be better served will bring to the notice of their undiligent husbands; a book in which the senses will speak to the heart, in which libertinage intends no cruelty towards the fair sex and rather restores the adored one to life than brings about her undoing, in which love, naturally considered and divested of scruples and prejudices, wearing always a smile. Peruse this book, you who are inclined to the worship of women or you in whom devotion has for some time slumbered; peruse it, I say, and you’ll own women for your darlings, beloved even as you lay claim to their cunts. But your abhorrence will only increase for that vivo clissequens, he who, his face decked in a long white beard, was dragged tottering out of the Bastille on the Fourteenth of July. May the enchanting tale I am sending to the printer sink his in merited obscurity!

A bad book penned with good intentions, this. I, Jean-Pierre Linguet, presently under arrest and confined in the Conciergerie, do affirm I have done this work, highly spiced though it be, with none but laudable purposes and useful aims. Incest, for example, is only included herein so as to provide the corrupted tastes of libertines with some vague equivalent of the abominations, the frightful cruelties with which our Sades lard their books to stimulate their depraved admirers.

My moral purpose and mine is as good as any other is to give those who have some spirit in them an ‘erotikon’, well-spiced and lively, which will encourage them to put a no longer lovely wife to the best possible use. But not by any means to the same use suggested by that cruel and dangerous book of Sade’s, Justine ou les malheurs de la vertu, which of late has enjoyed such a regrettable popularity.

I have thus still another important intention. I wish to preserve women from cruelty’s delirious excesses. The Anti-Justine, no less highly seasoned, no less ambitious in its situations than Sade’s novel, but altogether unbarbarous, will henceforth prevent men from resorting to barbarity. The publication of this antidote is a matter of urgency, and if dishonour in the eyes of purists, fools and thoughtless censors is to be my lot, I accept it willingly in order to come to the aid of my countrymen.

There remains much that might be said about the scenes I am going to bring before the reader’s eye, hoping to make him forget what he saw in Justine and prefer The Anti-Justine. My book must just as much surpass the other in voluptuousness as it yields to Justine in cruelty. The reading of but one chapter must be enough to move a man to the proper exploitation of his wife, young or old, pretty or ill-favoured provided the lady have a hygienic acquaintance with the bidet and a well-developed taste in footwear.

Chapter 1: The stiff-pricked youngster

I was born in a village which lies near Reims and I was familiarly known as Cupidonnet. From earliest childhood I had a decided fondness for pretty girls; I had a particular weakness, above all, for prettily turned feet and cunning little shoes, in which predilections I bore a resemblance to the Grand Dauphin, son of Louis XIV, and to Thevenard, the actor at the Opéra.

The first girl to get my youthful prick up was an engaging peasant who used to take me to vespers. With one hand poised on my naked ass, she was wont to tickle my little balls and, feeling my cock rise, would kiss me upon the mouth with an entirely virginal impetuousness, for although well-behaved, she was also hot-blooded.

The first girl upon whom I in turn laid my hands, in consequence of my enthusiasm for pretty footwear, was the youngest of my sisters, Genovefette. In all I had eight sisters, five older than myself and by a former marriage, and three who were younger. The second-born of the earlier crop was as pretty as can be: I’ll have a great deal to say about her; the hair thatching the cunt of the fourth was so silken and fine ’twas all by itself a delight; the rest were ugly; each of my three younger sisters was more of a provocative little minx than the others.

Now Genovefette, the most voluptuously attractive, held the first place in my mother’s preference, and, returning from a trip to Paris, she brought back an exquisite pair of slippers for her. I watched Genovefette try them on, and the sight caused me to get violently erect. The following day – it was a Sunday – she donned some new sheer white cotton stockings, a corset which drew in her waist, and with that luscious ass of hers, although she was still of tender age, she must have made my father’s prick stand up, for he bade my mother send her from the room. I had hidden myself under the bed so as the better to see my engaging sister’s shoe and lower leg.

Directly Genovefette was gone, my father had at my mother, and there, upon the bed below which I lay concealed, gave her a good fucking, the while saying: ‘Oh, I tell you, keep an eye on your beloved daughter, she’s going to have a devilish temperament, I warn you … but she’ll have to compete fiercely, for I fuck like a steer, and look at the rewards I have for my trouble, cunt-juice, you’re squirting it out like a princess …’ I noticed that, behind the half-opened door, Genovefette was watching and listening to what was happening. My father was right: that pretty rascal was later deflowered by her confessor, and thereafter fucked by virtually everyone, but today she’s all the wiser for it.

This 1930 edition of L’anti-Justine includes a new introduction by ‘Helpey’, the pen-name of poet and bibliophile Louis Perceau. The imprint is ‘Ile Sainte-Louis: De l’imprimerie de Monsieur Nicolas’, and the edition is of 350 numbered copies.

We are grateful to Steve Mullins of the Olympia Press website (www.parisolympiapress.com) for these illustrations.