Twilight and rebirth – sex and art at the turn of the twentieth century

Around the year 1900, and increasingly into the early years of the twentieth century, there was something of a sexual identity crisis in society generally and in art particularly.

Long-held assumptions about male dominance and virility and female passivity and innocence were being questioned, and the implications of radical change, especially in the bedroom, were both exciting and frightening. This short essay explores some of the ways in which these changes were being experienced by the artists and writers who lived through them.

The name of Hans-Jürgen Döpp will be familiar to anyone interested in the history and dissemination of erotic art. His many books include 1000 Erotic Works of Genius, Objects of Desire, The Kiss, Temple of Venus and Paris Eros, and after fifty years of careful gathering has amassed a large and fascinating erotic art collection. Hans-Jürgen is based in Frankfurt-am-Main in Germany, and for many years taught sociology at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe-University. As well as collecting, teaching and writing he has curated many exhibitions and helped develop and collect for several erotic art museums. He now publishes a wide range of specialist publications under the Venusberg imprint (www.venusberg.de).

This translation is a shortened version of Hans-Jürgen’s book, Jahrhundert-Dämmerung: Erotische Kunst zu Beginn des 20 Jahrhunderts, which can be ordered from his website.

We are delighted that Hans-Jürgen has contributed this piece to our website.

Twilight and rebirth

For many people, especially in Europe, the early years of the twentieth century were distinctly upbeat. As historian Stefan Zweig writes in The World of Yesterday, ‘A wonderful carelessness had come over the world, for what was to interrupt this upswing, what was to inhibit the vigour that kept drawing new strength from its own momentum? Europe had never been stronger, richer, more beautiful, had never believed more deeply in an even better future.’ A whole generation decided to become more youthful; being young and being fresh was what mattered.

The year 1900 was seen as marking a transition between two ages. Youthfulness replaced decadence, vitalism replaced morbidity, city euphoria replaced city escape. Little Hanno in Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks of 1901 saw the symptoms of decay, the old ways in a process of ‘crumbling, ending, closing, decomposing’. Already in 1897 the sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies was writing of a ‘process of decomposition, the increasingly visible disruption of culture. The old orders of life are in the process of disintegration at an accelerated pace in the century that is now drawing to a close’.

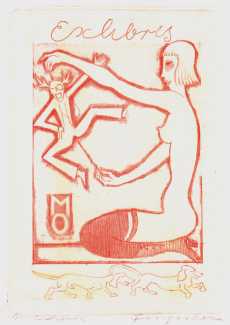

In Germany at the beginning of the new century, there was an eruption of overtly erotic images, expressing a new attitude towards both life and art. A ‘new way of seeing’ became a driving force in modern art, a crusade for sincerity, for freedom of expression, which no art establishment could command or permanently prevent. This sincerity included recognising that the arts are deeply rooted in sexual and other primal drives. The academic painters had flirted with these instincts, but only very in a veiled way; the salon painting of the time was little more than socially-permitted pornography.

Many artists who wanted to break down the prevailing conventions formed associations and secessions in opposition to the traditional academies. The separatist wave began in 1892 with the Munich Secession around Franz von Stuck, followed by the Vienna Secession under the leadership of Klimt in 1897, and finally the Berlin Secession in 1898. Robert Musil describes the mood that ushered in the dawn of modernity: ‘All over Europe the oil-slick spirit of the last two decades of the nineteenth century suddenly felt like a debilitating fever. Nobody knew exactly what was to replace it – a new art, a new person, a new morality, or perhaps a complete restructuring of society.’

The emancipation of the modern woman

In no other area of public life was there such a comprehensive transformation as in the relationships between the sexes. In his first book, The New Spirit of 1890, Havelock Ellis declared that the advance of science, democracy and women could no longer be stopped. ‘The rise of women to their fair share of power is guaranteed,’ he wrote optimistically.

The increasing participation of women in production was the economic reason for the changed position of women in relation to men. The growing economic importance of women’s work led to demands for political, legal and social emancipation. Modern women insisted on access to academic studies, equal treatment in property and divorce law, and voter participation. Issues around power and sexuality were an important focus – breaking down the limitations of marriage and conventional morality were part of the programme of the women’s movement from the start. The struggle for contraception and abortion was linked both to women’s sexuality and to legal and economic emancipation.

A new type of woman started to appear in literature and art at the beginning of the century. The historian Curt Moreck suggests there were three types of ‘new woman’:

- the ‘grand-dame’, for whom the limits of bourgeois erotic morality as expressed in marriage were still worthy of respect but were no longer sacrosanct.

- the ‘unmarried adulteress’, who respected the limits of morality and guarded her perceived virginity as her assurance of marriageability, yet was quite comfortable being seen as sensual.

- the ‘Lulu’, who was free of any inhibitions, no longer turned to erotic conventions, and was happy to be an active participant in intimacy rather than a passive object of pleasure.

The emancipation of women, the youth movement, the findings of psychoanalysis – all these led to freer and more unbiased views. The erotic became more socially acceptable as an acceptable arena of exploration, an important element of art and literature. Where sexuality had been dealt with insecurely and fearfully, the silence had now been broken. As Stefan Zweig has written, in the first ten years of the twentieth century ‘more freedom, informality and impartiality were regained than in the previous hundred years. There was a different rhythm in the world.’

The sexual question

The laborious process of removing taboos led to many prosecutions and judicial processes to which artists at the turn of the century were subjected. In 1900 there were protests by artists and scientists in cities including Berlin and Munich against the planned Lex Heinze, the law against immorality in art. The process of removing taboos was spearheaded by a number of influential authors, including Wilhelm Bölsche, Richard von Krafft-Ebing, Auguste Forels, Magnus Hirschfeld and Oscar Weininger. In 1897 Albert Moll published his studies on sexual libido, and Havelock Ellis his Studies in the Psychology of Sex. In 1907 Iwan Bloch published his broad-based anthropological work on sex and modern culture, and in 1908 Magnus Hirschfeld published the first sexological journal, allowing eroticism to become an acceptable subject for cultural analysis.

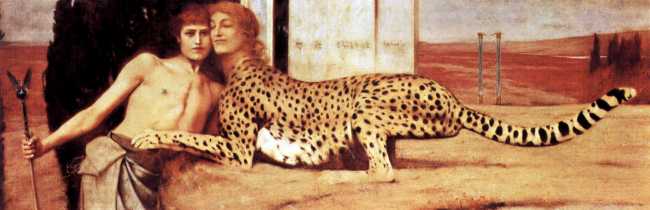

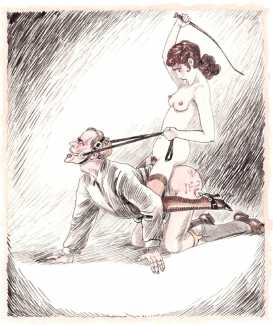

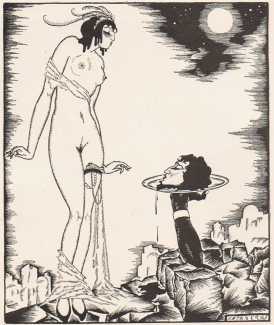

Not everything, however, was progress. For better and for worse, the dark side of sex was also being explored. Artists like Franz von Stuck, Edvard Munch and Fernand Khnopff were producing imagery in which women appear as vampires and Medusas – demonisation and misogyny, fascination and horror were part of men’s fantasies about women’s newly-acknowledged sexual power. This apparent hatred of women, which broke out around the turn of the century, was complemented by a cult around the concept of masculinity. The ‘sexual question’, the true nature of femininity and masculinity in a world where the very concepts were being questioned after centuries of stereotyped status quo, was both liberating and frightening.

‘This much is certain,’ writes Peter Gay in Education for the Senses, ‘no other period portrayed women as consistently and nakedly as vampire, castrator and murderer. And the well-known dialectic of action and reaction was a key characteristic of the time – the fears of men were crystallised by the activity of feminists, and male fears showed the way for the activities of feminists.’

Keeping female sexuality under control

It is clear that many men, both then and now, had a difficult relationship with women’s sexuality. Fearing their own sexual limitations, the idea of the insatiable woman was at the same time both seductive and threatening.

Writing in 1903, Oscar Weininger in Sex and Character aired many of the concerns of men at the time. These included the idea that women ‘have the power to drive men crazy, losing control to a woman who surrenders in orgasm’. He suggested that ‘the phallus has a mesmerising, fascinating effect on women’, and that ‘the prostitute fantasises being crushed in coitus, becoming unconscious with desire, wanting wants to perish in all-embracing lust.’ In a reactionary analysis that led to an inevitable feminist backlash, he asserted that ‘the phallus is what makes the woman absolutely and terminally unfree’. Interestingly, however, Weininger welcomed the emancipation of women, imagining that as women were freed from the yoke of animal sensuality all relationships could become less emotional and more controlled. ‘Overcoming femininity is what matters most’, he wrote in conclusion.

The complementary counter-image to Weininger’s pan-sexual woman was the nineteenth-century fiction of women’s lack of sexual desire. As recently as 1894, in the ninth edition of his classic Psychopathia Sexualis, Krafft-Ebing claimed that ‘without a doubt the man has a livelier sexual need than the woman. Following his powerful natural instinct, he desires a woman of a certain age.’ For women it was quite different: ‘if women are spiritually developed and well-bred, then their sensual desire is low. If this were not the case, the whole world would be a brothel, and marriage and family would be unthinkable.’

So what would women do to men, once unconstrained from the bonds of male fantasy? For many men, feminism was nothing less than a threat of castration.

The fear of female rule

The economic, social and moral transformations of the early years of the twentieth century created many false prophets, all too happy to intensify these fears. Johannes Birlinger, author of The Cruel Woman: Sexual, Psychological and Pathological Documents on the Cruelty and Demonia of Women, typically wrote, ‘We are standing before the wide-open gates of a new age of female rule. It remains to be seen whether this period in human history will destroy marriage, the previous cornerstone of patriarchy, or whether it will adapt the institution to the changing social structure. Will the coming gynaecocracy be a long-lasting humiliation period for men, or a transition to a feminine emphasis on cultural, social and economic life? I can see only one outcome of this powerful women’s offensive so far – the imminent end of male rule and the beginning of female rule.’

The fundamental power of masculinity was shaken; the dominance of men in society could no longer be tacitly accepted. Neither the ‘social question’ nor the ‘sexual question’, both fundamental weaknesses in bourgeois culture, could be ignored any longer. The struggle would be long and bitter, but deep and lasting change was now inevitable.

‘Happy are they who forget what cannot be changed’ runs the popular refrain from Johann Strauss’s Die Fledermaus of 1874. Freud gave a name to this inertia – repression.

A world of erotic angst

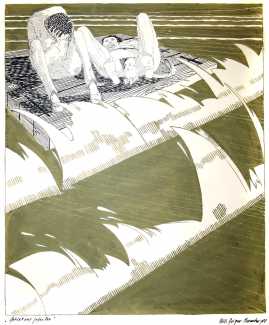

Erotic art around the turn of the twentieth century painted an unsettled, gloomy picture of sexuality. Lust went hand in hand with fear and aggression. The conflict-laden nature of these images is more anti-erotic than an expression of sensual joy. Not Eros, but its opponent Anteros, seemed to be at work in them.

How does this relate to the profound social changes of the time, and how did the conflict-ridden social external world transform into the psychological internal world of individual artists? These artists were anti-bourgeois, feeling a growing sense of menace, allowing themselves to feel the conflicts and ambivalences of the bourgeois world as a threat from within, from the underworld of the unconscious.

Once Freud had allowed the sexual inhibitions of his prudish culture to be more than merely irrational, the relaxation of these inhibitions brought forth new irrationalities. And these irrationalities found expression first and foremost through the prelinguistic medium of art.