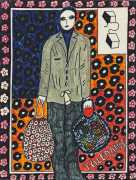

Dorothy Iannone was born in Boston, Massachusetts; her father died when she was two years old and she was raised by her mother Sarah. Dorothy graduated in 1957 with a BA in American Literature, and went on to study English literature at Brandeis University. In 1958 she married the painter James Upham, and the couple moved to New York. The following year Iannone taught herself to paint. Between 1963 and 1967 she exhibited with her husband at the Stryke Gallery, an exhibition space the couple ran in New York, and travelled frequently to Europe and Asia. In 1961 the US Customs at Idlewild Airport, New York, seized her copy of The Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller, which was banned at the time. With assistance from the New York Civil Liberties Union Iannone sued the customs service, which resulted in her book being returned and the ban on Miller lifted. This experience with censorship was to colour much of her later experiences with erotic art.

Dorothy Iannone was born in Boston, Massachusetts; her father died when she was two years old and she was raised by her mother Sarah. Dorothy graduated in 1957 with a BA in American Literature, and went on to study English literature at Brandeis University. In 1958 she married the painter James Upham, and the couple moved to New York. The following year Iannone taught herself to paint. Between 1963 and 1967 she exhibited with her husband at the Stryke Gallery, an exhibition space the couple ran in New York, and travelled frequently to Europe and Asia. In 1961 the US Customs at Idlewild Airport, New York, seized her copy of The Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller, which was banned at the time. With assistance from the New York Civil Liberties Union Iannone sued the customs service, which resulted in her book being returned and the ban on Miller lifted. This experience with censorship was to colour much of her later experiences with erotic art.

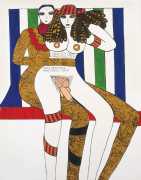

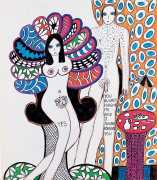

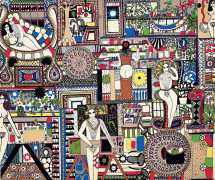

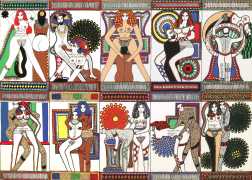

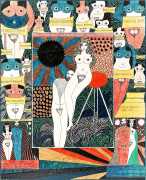

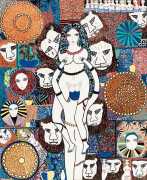

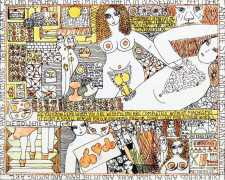

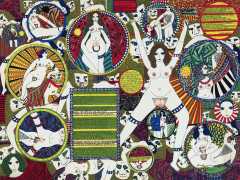

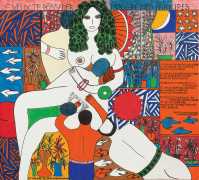

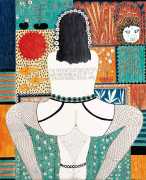

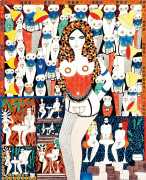

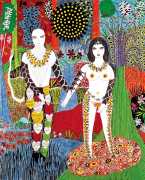

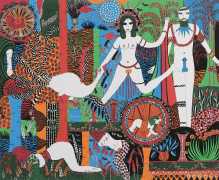

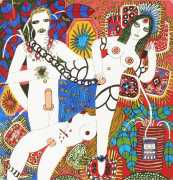

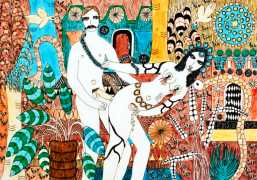

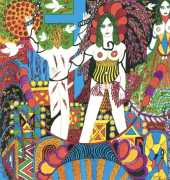

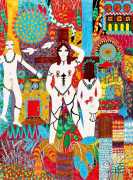

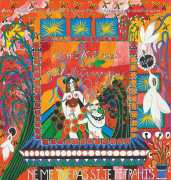

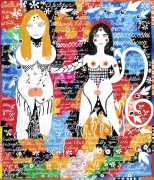

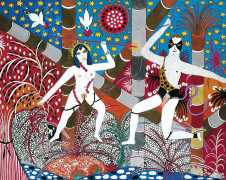

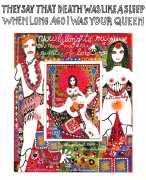

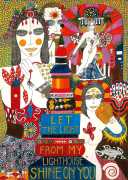

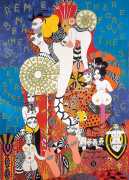

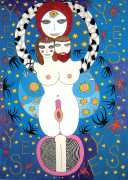

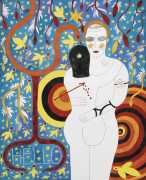

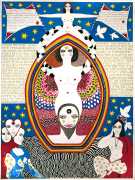

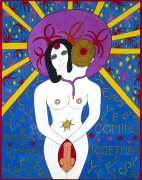

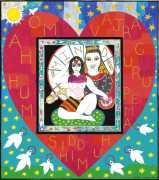

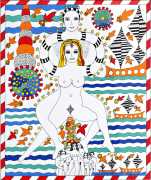

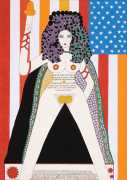

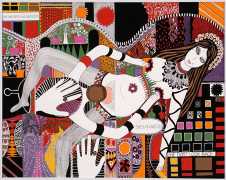

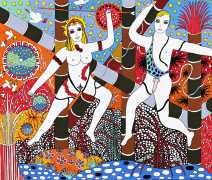

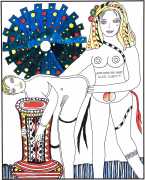

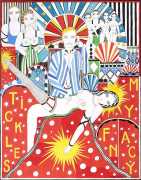

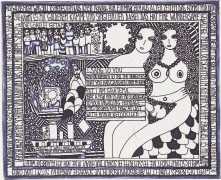

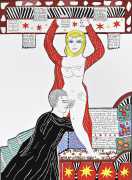

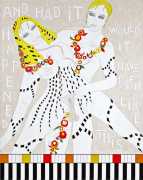

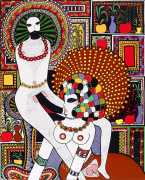

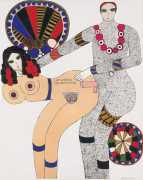

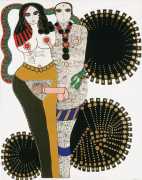

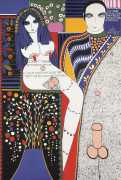

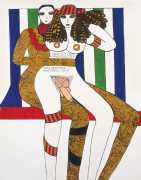

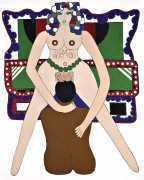

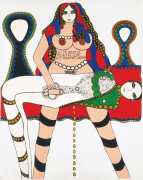

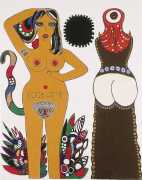

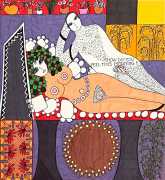

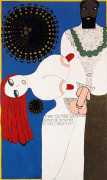

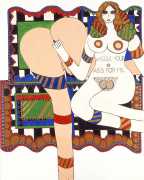

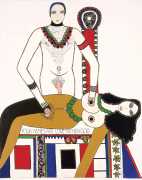

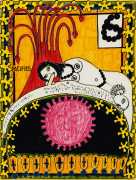

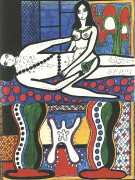

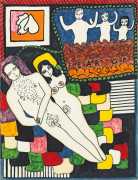

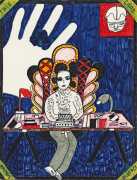

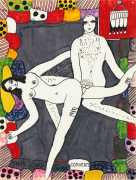

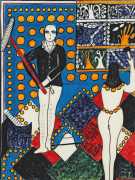

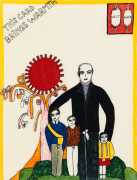

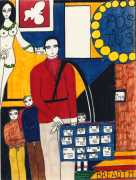

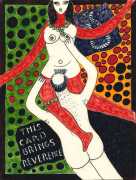

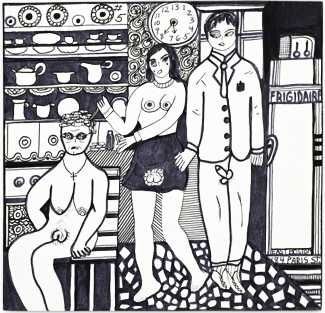

The majority of Iannone's paintings, texts, and visual narratives depict themes of erotic love. Her explicit renderings of the human body draw heavily from the artist’s travels and from Japanese woodcuts, Greek vases, and visual motifs from Eastern religions, including Tibetan Buddhism, Indian Tantrism and Christian ecstatic traditions. Her small wooden statues of celebrities with visible genitals, including Charlie Chaplin and Jacqueline Kennedy, were early examples of her insistence that humans are intrinsically sexual beings and that sex deserves to be visible and celebrated.

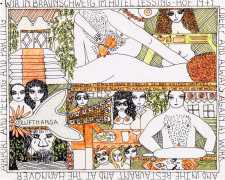

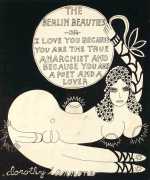

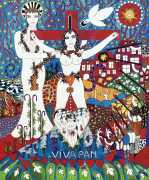

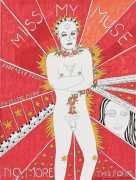

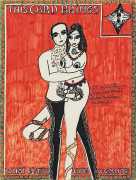

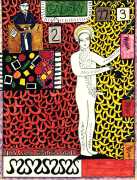

On a trip to Reykjavik in Iceland in 1967, Iannone met the Swiss artist Dieter Roth – Iannone separated from her husband just a week later. Iannone lived with Roth in Düsseldorf, Reykjavik, Basel and London until 1974, and Roth became Iannone’s muse and features in much of her artwork. One of her most noted works involving Roth is her book An Icelandic Saga, which vividly illustrates the artist’s first encounter with Roth and her subsequent breakup with her husband in the vein of a Norse myth. She also created paintings of her and Roth in sexual union as historical couples. Iannone and Roth remained close friends until his death in 1998.

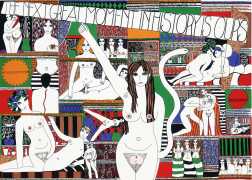

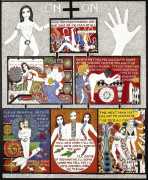

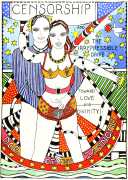

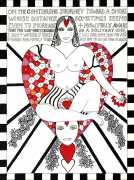

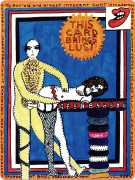

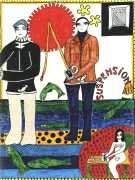

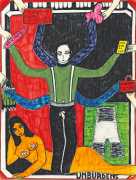

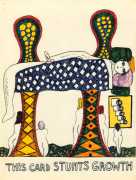

The explicit nature of Iannone’s work frequently fell foul of censors. Of the early censorship of her work Iannone wrote, ‘When my work was not censored outright, it was either mildly ridiculed or described as folkloric, or just ignored’. In 1969 the Kunsthalle Bern tried to censor Iannone’s work in the group exhibition Ausstellung der Freunde by requesting that she cover up the genitals of her figures. In protest Dieter Roth dropped out of the exhibition and the curator of the Kunsthalle Bern, Harald Szeeman, resigned. Iannone recalled the experience in her book The Story of Bern or Showing Colors (1970).

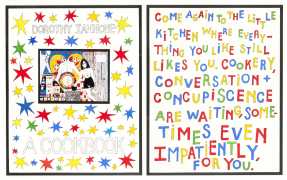

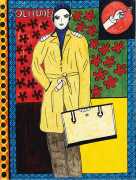

Iannone’s first solo exhibition in the USA, Lioness, was held at the New Museum in 2009, and since then her work has been featured in numerous group and solo exhibitions across Europe. In 2014 Kerber Art in conjunction with the Berlin Gallery for Modern Art published an in-depth study of Ianonne’s life and work, This Sweetness Outside of Time, with several essays by her friends including Thomas Kõhler and Annalie Lutgens. The same year the Migros Museum in Zurich published Iannone’s Censorship and the Irrepressible Drive toward Love and Divinity, an important and sensitive exploration of Dorothy Iannone’s lifelong battle with artistic suppression. Still highly critical of American values and conventions, Dorothy Iannone lives and works in Berlin where she has been a resident since 1976.

Dorothy Iannone’s work is well summed up in an article by Virginia Marchione which appeared in Griot magazine in 2015:

‘Iannone’s drawings, from Indian art and Egyptian depictions – quotations about Cleopatra appear often – to the psychedelic, are populated by figures in sexual ecstasy. The representations are replete with irony, subverted conventional dynamics, men and women, the stereotypes of domination and control, the sacred and the profane, and the roles of artist and muse. Thirty years ahead of her time, and ahead of the work of the British Artist Tracey Emin, Iannone published Lists IV in 1967, an artist’s book that contained a list of all the men she had slept with. But her political tension and sex was too much for those times, and after her art was subjected to censorship at an exhibition in Bern in 1969 she was boycotted and ignored for more than thirty years. Her artwork, with depictions of eroticism, unconditional love and transgressive sexuality, was also snubbed in the nineties, judged politically incorrect. Her art continues to reflect her long search for complementarity with the world and human beings, open and liberating eroticism, free of established roles and ever closer to the changes in contemporary society. Iannone’s drawings, sculptures and books have inspired generations of artists, and continue to strike a chord for their great narrative power and their unique and highly autobiographical character.’