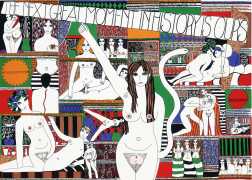

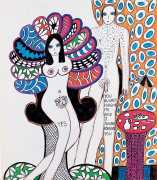

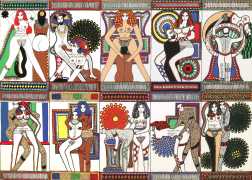

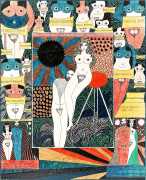

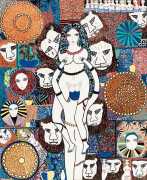

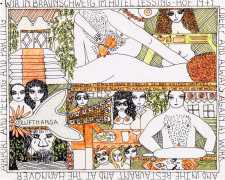

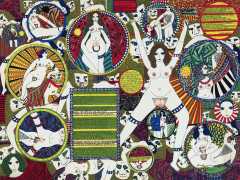

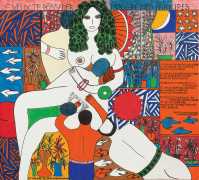

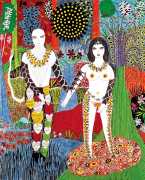

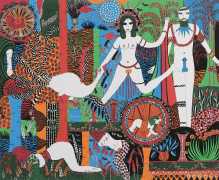

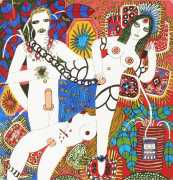

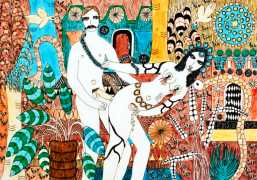

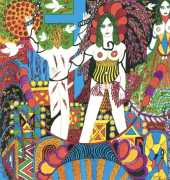

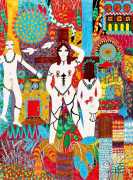

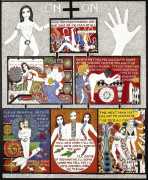

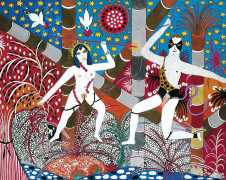

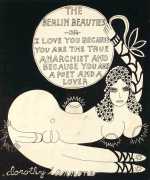

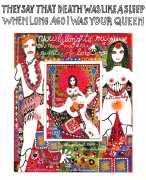

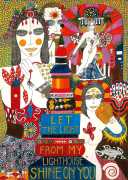

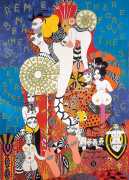

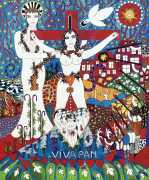

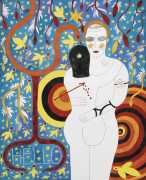

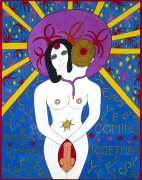

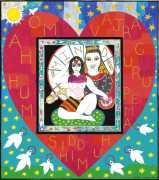

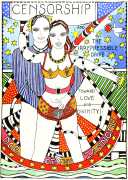

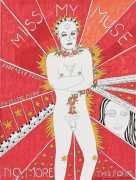

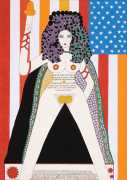

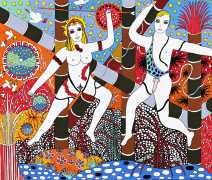

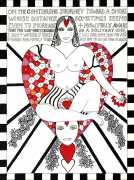

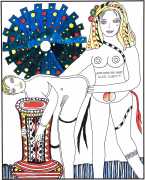

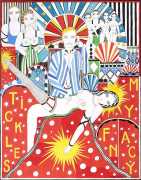

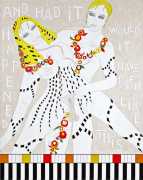

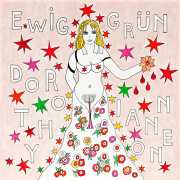

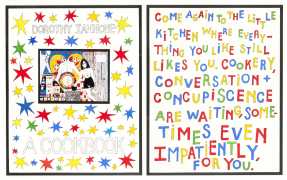

Dorothy Iannone’s work, shown here in chronological order from her 1968 ‘The Next Great Moment in History is Ours’ to her 2019 ‘Lady Liberty’, demonstrates both the breadth of her subject matter and the consistency of her very personal style, often combining line, colour and text into works of enormous depth and complexity.

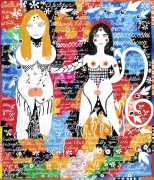

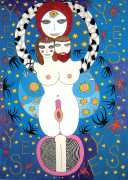

Her painting did not start in 1968 however. After some experimental abstract work in the late 1950s, in 1966 she started to create a series of cutouts of figures, many semi-naked, mounted on wood and around eighteen inches high, which she called simply ’People’. The explicit nudity inevitably created waves, and set Iannone on a lifelong path of fighting for artistic freedom and honest personal expression.

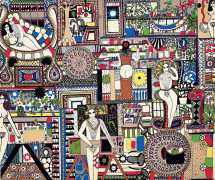

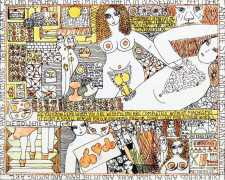

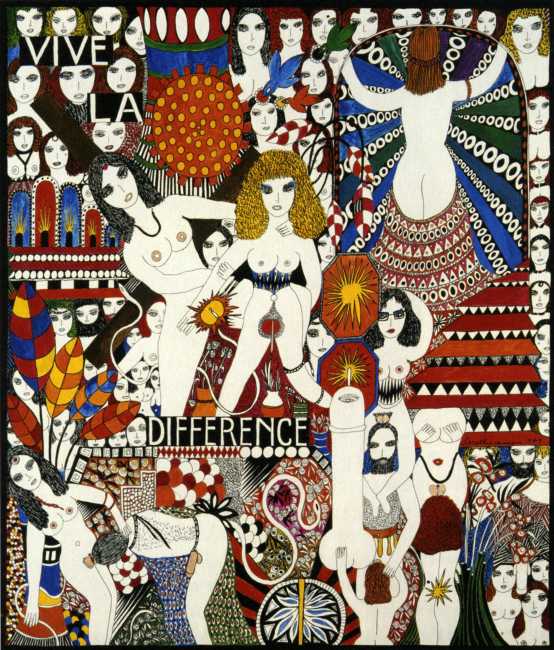

During a long and productive artistic journey, Dorothy Iannone has produced many hundreds of paintings, not to mention artist’s books, objects, films and videos (including a video of the artist’s face while masturbating). For anyone interested in finding out more about this remarkable woman, the 2014 book The Sweetness Outside of Time is essential reading, and to whet the appetite here is just one extract from the book, the beginning of Michael Glassmeier’s essay ‘Languages of Love’, where he looks at the complexity and significance of just one of Dorothy Iannone’s paintings, her 1979 ‘Vive la Différence’:

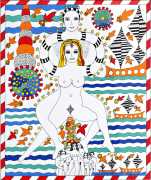

The colourful concentration and radiant effusiveness, the juxtaposition of writing and image, the mosaic of compact bodies and ornamentation and, finally, the explicit male and female genitalia in Dorothy Iannone’s works now and then generate a surplus of meaning that is confusing and not easy to decipher, although the message seems unambiguous. So we usually content ourselves with the message that dominates the field of reference, in many cases in decorative capital letters and together with proffered nudity, and we consign the labyrinthine mosaic to the realm of ornatus. However, it is those very details that make a painting by Iannone what it actually is in the first place. We are definitely dealing with a complex body of work – contrary to the superficiality ascribed to it by some interpreters – an oeuvre, that calls for in-depth treatment and some art-historical exertions. It is necessary to differentiate.

The colourful concentration and radiant effusiveness, the juxtaposition of writing and image, the mosaic of compact bodies and ornamentation and, finally, the explicit male and female genitalia in Dorothy Iannone’s works now and then generate a surplus of meaning that is confusing and not easy to decipher, although the message seems unambiguous. So we usually content ourselves with the message that dominates the field of reference, in many cases in decorative capital letters and together with proffered nudity, and we consign the labyrinthine mosaic to the realm of ornatus. However, it is those very details that make a painting by Iannone what it actually is in the first place. We are definitely dealing with a complex body of work – contrary to the superficiality ascribed to it by some interpreters – an oeuvre, that calls for in-depth treatment and some art-historical exertions. It is necessary to differentiate.

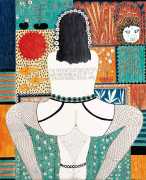

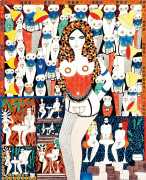

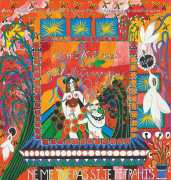

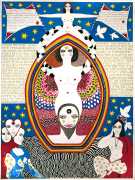

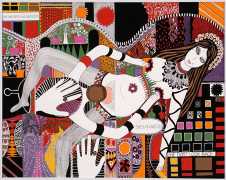

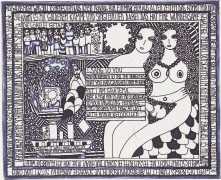

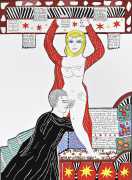

As if the artist herself wanted to invite us to make this intellectual effort, in 1979 she created the gouache ‘Vive la Différence’. In the upper half in particular, interspersed among the ornamentation at the left, the typically variegated intertwining forms in vivid colours feature rows and accumulations of female heads – sometimes isolated, sometimes in half-length portraits – that look straight at the viewer. They resemble each other in their stylisation, and yet their different coiffures and minimal, individualising facial features endow them with distinct characters. On the upper right, seen from the rear, there is a female nude with outstretched arms who is encircled by a kind of portal. Her red white and black patterned skirt is pulled down. Distinctive rays of blue, green and violet stripes and black and white ring-patterns emanate toward her from a perspectival distance, while to the left, on the same level, an orange-coloured abstract mandala rests at the bottom of a huge vase that is truncated by the upper edge of the painting. In their midst, flying over the women’s heads, are three bright birds with blossoms in their beaks. In the lower half of the painting, on the right, we see a heterosexual pair, and a penis floating above a group of three women. Next to it is a couple positioned to perform cunnilingus, with the head of the woman above seeming to be cut off by a red staircase with black and white patterned steps that leads heavenward. And next to it once again is a vertically stacked trio combination of fellatio, a woman with glasses straddling the shoulders of a man, and next to that a colossal isolated penis whose testicles are being touched by the woman below. Next to this is a floral mandala and another heterosexual couple, also engaged in cunnilingus. Behind the reclining standing woman rises a vase whose flowers flow into a field of female heads, and above them a few more steps leading up to five apsides of different sizes with flames in them. Finally, at the centre of the painting, are two large women, one blonde, one with black hair. The black-haired woman is sitting with her thighs wide open, her vulva ringed in flames; behind her is a wooden board which, together with a second board, creates the impression of a cross. She grasps a blonde woman – who is corseted, with a bejewelled vulva, and is standing with her legs apart – around the neck and one arm, as if wanting to draw her body toward her. A thin white snake completes the possible connection between the two women. Another snake slithers as ornamentation in front of a flowery pattern in the middle of the lower portion of the painting, and a third is found at the lower left in fine accompaniment to the sexual action. In the spaces between the white bodies and faces are a variety of plant and feathery peacock ornaments, patches of colour and stylised fire, while the white lettering is distributed along horizontal black bands from the upper left to the lower middle area in the painting.

This exercise in simply describing the painting raises so many questions. We are in a realm of white bodies enveloped by symbols, many from a Catholic iconography, whose most impassioned expression is found in that cross. The pictorial language makes sense when the sexualised activities are enhanced with visions of heaven and paradise, in which snakes naturally frolic, flames of love and the spirit flicker, the gates of paradise stand wide open, and a nude, seen from the rear, opens her arms to receive a perspectivally stylised shaft of light. The ascending stairway beneath the nude on the right is a symbol of transformation in almost all religions. In Dante it explicitly denotes the final hurdle to earthly paradise, from the vita activa to the vita contemplativa, preparing Dante for the encounter with Beatrice, who appears on a triumphal carriage in a sea of flowers to proclaim heavenly love.