Anyone who knows anything about art knows Edgar Degas’ attractive pastel drawings of young ballet dancers – they have an accessible and immediate charm. Degas is often thought of as one of the French Impressionists, but he was not keen on painting out of doors, en plein aire, preferring the studio, and called himself a Realist rather than an Impressionist. But Degas was more than just a painter of pretty dancers, and as the art historian Norbert Wolf has written such a readable and authoritative introduction to the (now sadly out of print) Prestel volume Degas: An Erotic Sketchbook, we happily leave you with his words.

Anyone who knows anything about art knows Edgar Degas’ attractive pastel drawings of young ballet dancers – they have an accessible and immediate charm. Degas is often thought of as one of the French Impressionists, but he was not keen on painting out of doors, en plein aire, preferring the studio, and called himself a Realist rather than an Impressionist. But Degas was more than just a painter of pretty dancers, and as the art historian Norbert Wolf has written such a readable and authoritative introduction to the (now sadly out of print) Prestel volume Degas: An Erotic Sketchbook, we happily leave you with his words.

Immature female ballet dancers seen in an unsteady, flickering light – that is what still enchants the public today and accounts for the continuing popularity of Edgar Degas. The son of a banking family with Neapolitan, French and Creole roots, this brilliant artist in oil and pastel, occasional sculptor and inspired draughtsman’s real name was Edgar Hilaire Germain de Gas.

But away from the world of the stage and its artificially enticing fabrics, Degas devoted himself to a quite different – in fact, shockingly different – kind of ‘flora’. In 1886 the critic Henry Fèvre described in the simplest of language – ‘Monsieur Degas bares for us the bloated, doughy flesh of prostitutes’ – how Degas chose a particular species of prostitute, not the grandes horizontales, who granted the favour of their affections and their arts only to the rich and powerful, but the residents of cheap stews and not so cheap brothels: fat, naked figures, who cleaned their bottoms in wash bowls, as ‘large as tubs’. Many contemporary voices never failed to add the cynical side blow that such earthy intimacy came from the hand of an artist whose friend Edouard Manet had claimed in 1869 that he was incapable of loving a woman – his virility was channelled solely and exclusively into art. Paul Gauguin spread the word, as did Vincent van Gogh, who in a letter to a Emile Bernard called Degas a wimp, saying that, if he had ‘screwed’ women (as he put it), he would not have been able to study and paint them so unerringly well.

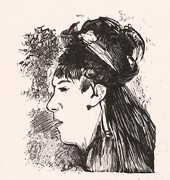

As an artist, Degas did not start out down this degenerate, carnal road to cherchez la femme. He began with history paintings, inspired by romantic artist Eugène Delacroix and the elegant neoclassical lines of Ingres (whom Degas admired all his life). And the first high points of his oeuvre were portraits of the grande bourgeoisie, which were notable for the ‘greatest physiognomical intelligence that the nineteenth century ever encountered’, as Willibald Sauerlander commented. More glamorous subjects appeared in his works by the mid-sixties, in particular jockeys and gentlemen riders of the turf.

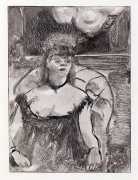

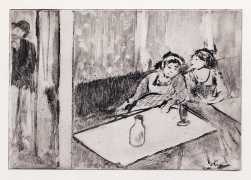

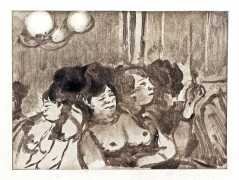

Then, post-1870, in undoubtedly his most active and experimentally creative decade, Degas suddenly turned to the lesser female forms of the proletariat. They went about their work off and onstage in the arenas of modern metropolitan life, the washerwomen and ironers in dilapidated backyards, the ballet dancers, the chanteuses from the café-concerts, the protagonists of the pleasure palaces – in short, the female prey of ferocious predatory capitalists; recruits to a demi-monde who often as not ended up in the hooker sisterhood. It was not for nothing that Paris was called the ‘bourse, boulevard and brothel of Europe’; and it was not for nothing, as for example Balzac observed, that the word ‘rat’ – as notably in the petits rats of the ballet – was used for ten or eleven-year-old girls served up at the theatre or the opera for the wanton pleasures of elderly debauchees.

In 1866, Jacques Offenbach lobbed La vie Parisienne into the operetta firmament. It celebrated an orgy of dissipation, dragging it audaciously from the private sphere out into the open, into the public sphere of theatres, music halls and variety shows, as well as the brilliantly gas-lit café nightspots that, like the brothels, museums, racecourses and grands boulevards, served as places where the upper crust, dandies and demi-monde came into contact. As true Bohemians, artists were more than willing to be caught up in it all.

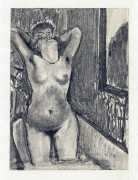

Manet acted as the hub of a group that met up regularly in the Café Guerbois in Montmartre. Others in the group were now familiar names such as Fantin-Latour, Renoir, Bazille, and occasionally Cézanne, Sisley, Monet and Pissarro – most of these would later make their names as members of the Impressionist group; other regulars were writer Emile Zola and the photographer Nadar. Degas did not feel particularly at ease at these rowdy encounters but he nonetheless took part in them, very much stimulated by the progressive-minded environment, where la vie moderne and its scandalisation were pursued with much passion. The pursuit particularly took the form of paintings of nudes – female, of course, because heroic male nudes were no longer required. Of course, it was not the fashionable nudes with which Hippolyte Flandre, Alexandre Cabanel, Constantin Guys or Jean-Louis Forain filled their canvases that provoked the public, but the unvarnished figures dug up from the shadowy depths of modern metropolitan life.

In 1865, Manet’s ‘Olympia’ was the sensation of the annual Salon. Manet had submitted the painting as a reaction to the 1863 Salon, in particular in response to Cabanel’s ‘Birth of Venus’. To quote Eberhard Roter, the latter nude looks as if ‘the spirit of sensuality had lodged in a cream pudding’. The foam-born goddess offered up her smooth, enamelled charms to the public almost absentmindedly. And the public was delighted. Napoleon III bought the picture on the spot at the exhibition. But why was this painting not felt to be indecent whereas two years later Manet’s ‘Olympia’ was? Undoubtedly because the nudity Cabanel offered was tricked out in mythical fancy dress, whereas Manet dispensed with the allegorical or mythological alibis for his reclining cocotte. A decade later, Degas was incomparably more radical in this respect. So radical in fact that even not so long ago American feminist art historians were still dismissing Degas’s glimpses of the boudoir – for example, the fat nude in the pastel ‘The Morning Bath’, who props her hands on her buttocks with relish – as the voyeuristic thrill of a sexually inhibited bachelor artist.

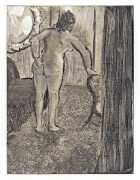

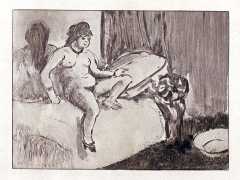

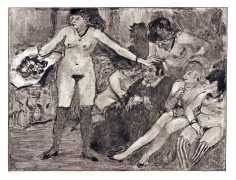

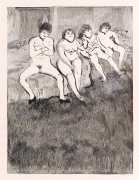

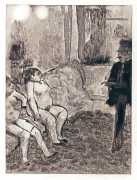

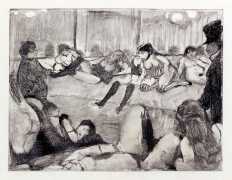

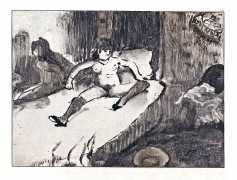

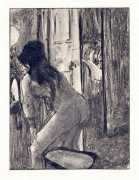

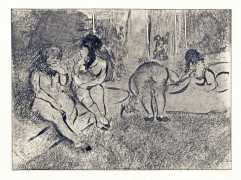

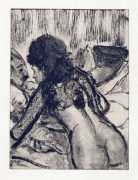

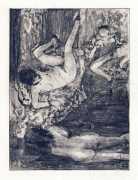

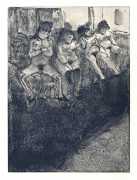

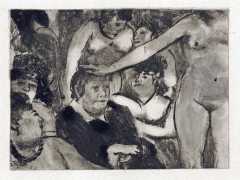

How off the mark is this statement, even in view of the intimate glimpses that Degas allowed himself in the grandiose series of nearly two hundred brothel monotypes he did between 1876 and 1878? Most of them remained in the studio, and after Degas’s death his brother is supposed to have destroyed approximately seventy drawings, in order to protect the family reputation. Picasso, however, saw Degas’s graphic works as his supreme achievement, and endeavoured to buy up as many as possible.

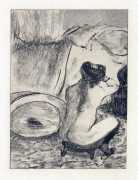

A monotype is a drawing done on a copper, zinc or glass plate in coloured printing ink or spirits of turpentine and preferably run off as a single print (a second print would come out extremely pale, as scarcely any ink would be left on the plate). An alternative procedure would be to employ the opposite technique – the plate is coloured black, and areas that have to be light in the print are wiped clean with a cloth or the fingers. The two procedures can also be combined. In such cases, Degas did a second print of the monotype in a paler or ‘ghost’ pull, which he then went over with pastels.

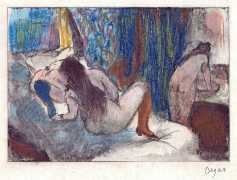

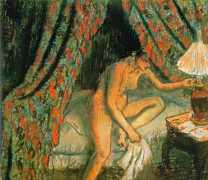

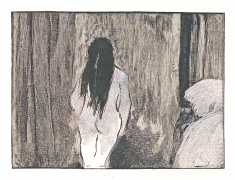

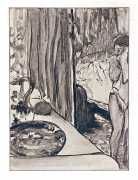

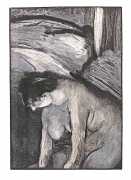

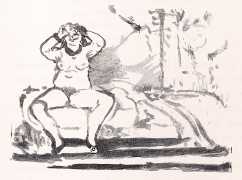

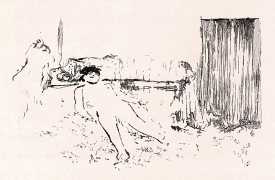

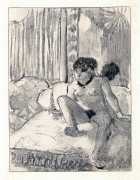

This was then the technique in which he did the brilliant series of brothel or bathing scenes (at the time only better-class brothels used the metal bath-tubs imported from England – middle-class women bathed extremely rarely, as this was considered unhealthy for the female body). Degas’s intimate but unsentimental and precise eye homed in on his fleshy sitters, making notes of the scene, which he recreated afterwards in the studio. Generally the women didn’t pose for viewers of the picture but for voyeurs on the spot, including potential clients who, if shown at all, feature marginally: and these were not acts of seduction. They are inelegant and clumsy, baring their carnal wares obscenely as an overt ‘here you are’ gesture. Though a great portraitist, Degas dispenses here with any kind of individualization of faces. He puts vulgarised physiognomies on the corpulent, bloated bodies of whores who have abandoned any pretense at perfection (inhabitants of brothels were scarcely allowed out, so they never encountered fresh air – which is why they tended to fleshiness and pallid complexions). Here and there, the ‘monotypist’ left his fingerprints on the women’s epidermis (where he had wiped away the ink), as if he had pawed their skin and felt the consistency of the flesh.

Direct sexual acts feature in only two of the monotypes. Degas increasingly focused step-by-step on the subject of the women bathing and drying themselves and resting after the provision of sexual services has been concluded, being less interested in reportage than capturing the physical presence of the women and bringing out their animal sexuality. These monotypes always go beyond pure genre pictures. Most of them take us into confined interiors, in which everything we can see stands out from a shadowy, twilit background or is partly scratched out, in which bodily functions and disillusionment with sex appear as emanations of an oppressive ambience.

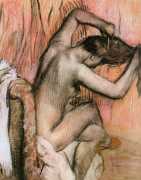

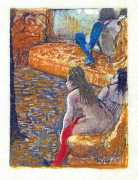

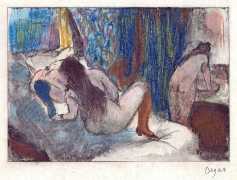

Around 1885 Degas increasingly turned away from monotypes in favour of pastels, with which he caused a notable stir at the eighth and final Impressionist exhibition in 1886. The exhibition catalogue mentions female nudes bathing, washing, drying themselves, towelling themselves off, combing their hair – thereby itemising the subjects that principally interested Degas in the last twenty years of his career. It is a moot point whether the subjects consist exclusively of women of the horizontal profession going about maintenance of their occupational assets. In any case, that is a secondary matter compared with the principal artistic concern of making female nudes the protagonists of an avant-garde picture production. Sculpturally conceived body shapes coincide with the exciting rhythm of decorative work. Decentralised compositions influenced by Japanese woodcuts, with bold foreshortenings and choices of pictorial field, steep perspectives and the simultaneous compacting of all three-dimensionality into the plane, now dominated the visual character of the works.

Degas – whom fellow Impressionist Camille Pissarro claimed was the greatest artist of his time, even though Degas always subordinated the Impressionist dissolution of form to classical linearity – was not in the least inhibited in his presentation of female nakedness, not even from a socio-critical viewpoint. He ‘bared’ the female body for the purpose of artistic experimentation and as an iconographic signal that modern society hounded subversive artists and whores alike into existential no-go areas. Such metaphorical allusions were one more reason why fellow painters such as Toulouse-Lautrec and Picasso esteemed the pictures Degas created of women more than anything.