To English-language readers, Nicole Claveloux is best known as the author of The Green Hand, a collection of illustrated stories from the 1970s, considered by many to be among the most beautiful comics ever drawn – whimsical, intoxicating, taking her reader into lands that are strange but oddly recognisable, filled with murderous grandmothers and lonely city dwellers, bad-tempered vegetables and walls that are surprisingly easy to fall through. French children have much more choice, from Private Detective Grabote and Dracula Spectacula to classics like Alice in Wonderland her bold (and sometimes a little scary) illustrations have held their imagination since the first comic book she illustrated, Hop-là, appeared in 1971.

To English-language readers, Nicole Claveloux is best known as the author of The Green Hand, a collection of illustrated stories from the 1970s, considered by many to be among the most beautiful comics ever drawn – whimsical, intoxicating, taking her reader into lands that are strange but oddly recognisable, filled with murderous grandmothers and lonely city dwellers, bad-tempered vegetables and walls that are surprisingly easy to fall through. French children have much more choice, from Private Detective Grabote and Dracula Spectacula to classics like Alice in Wonderland her bold (and sometimes a little scary) illustrations have held their imagination since the first comic book she illustrated, Hop-là, appeared in 1971.

Nicole Claveloux studied at the School of Fine Arts in her native town of Saint-Etienne, in the Loire valley in central France. After her studies she moved to Paris, where she started working as an illustrator in 1966. Her best-known character, L’insupportable Grabote, appeared in 1973, published by Harlin Quist. In 1976 Claveloux created ‘Planche-Neige’ (a play on Snow-White or Blanche-Neige) for the feminist magazine Ah! Nana, and started contributing regularly to the comic magazine Métal Hurlant. During the 1980s she published a popular range of books for younger children which she wrote and illustrated, including Tout est bon dans le bébé (Everything in the Baby is Good) and Histoires de clounes (Clown Stories). In 2005 her modern fairy tale Un roi, une princesse et une pieuvre (A King, A Princess and an Octopus) won the Junior Prix Goncourt.

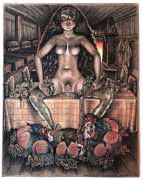

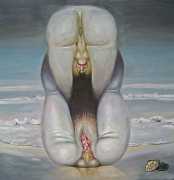

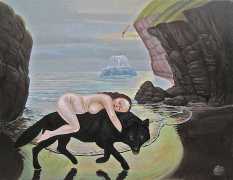

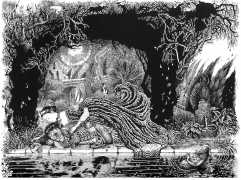

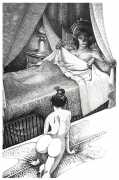

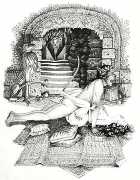

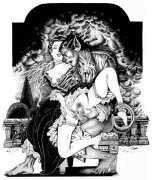

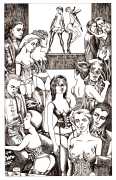

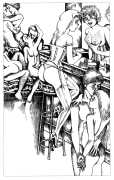

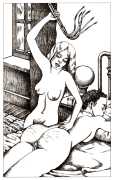

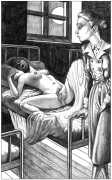

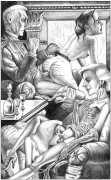

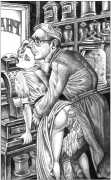

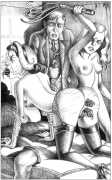

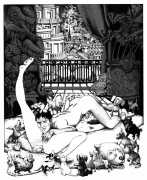

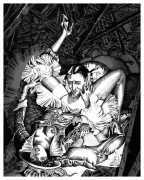

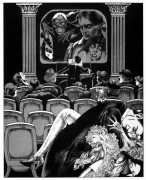

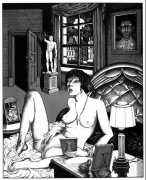

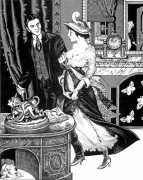

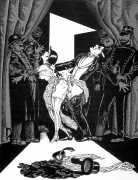

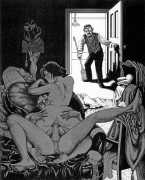

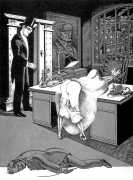

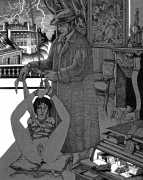

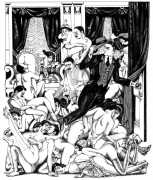

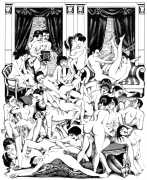

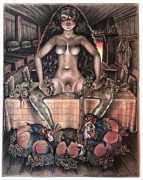

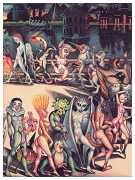

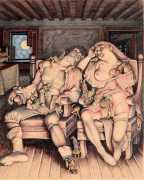

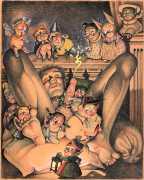

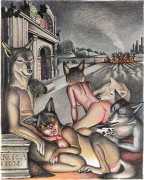

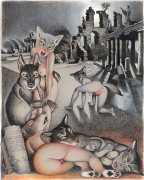

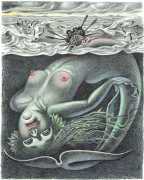

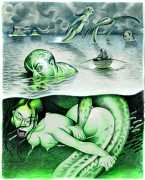

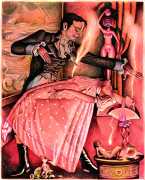

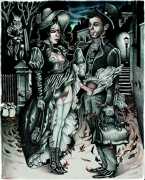

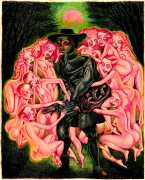

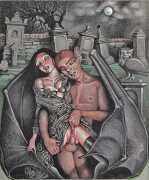

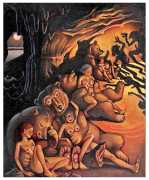

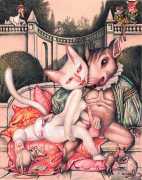

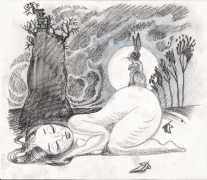

But there is another side to Claveloux’s skills, which first appeared in print in 2003 with an adult version of Beauty and the Beast, which she was at the same time illustrating for a children’s version. Two other highly original and imaginative volumes appeared – a dark Parisian tale set in the 1900s, and a collection of fairy tales, myths and legends. During this period she produced some striking landscape-style paintings, at the same time sexually explicit and sensually compelling, a selection of which we have included here.

In October 2008 the arts blog Li-An interviewed Nicole Claveloux about her erotic work; as it says more about her and her inspiration than we ever could we have translated it in full:

The last two books that you illustrated are erotic. Is this a coincidence, or a desire to orient yourself towards the genre?

The last two books that you illustrated are erotic. Is this a coincidence, or a desire to orient yourself towards the genre?

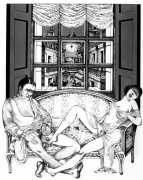

It really just happened, without me making a big decision about what to do next. It was a sort of desire I had had for a while. I worked on them alongside my children’s books; in fact Professeur Totem et Docteur Tabou appeared between the two erotic books. I don’t see the two genres as completely separate; the themes mingle. In 2001, I illustrated Beauty and the Beast in the original text by Mme Leprince de Beaumont (published by Éditions Thierry Magnier), and it made me want to continue, using the same two characters and telling their intimate adventures, but this time for adults. I’m not the only one to do this; many illustrators have practiced several genres simultaneously, for example Feodor Rojankovski and René Giffey.

Each of the books has text by a person who hides behind a pseudonym – the Marquis de Carabas and Maurice Lerouge. Do these people really exist?

The Marquis de Carabas and Marcel Lerouge are one and the same person behind these pseudonyms, one borrowed from Charles Perrault’s Puss in Boots, the other parodying the name of a author of a well-known early twentieth century novel. The author (actually Charles Poucet) and I work backwards – I draw scenes according to more or less vague ideas, and when I have accumulated a certain number I pass everything on to him; he then puts the images into an order, builds a story, and writes his text to correspond with my drawings. That’s the opposite of what I usually do, and it’s a very pleasant way to work. Sometimes we complete the story with a few additional drawings to bridge between scenes.

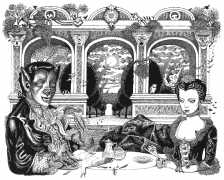

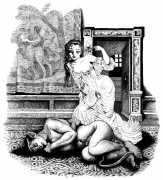

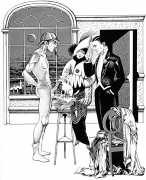

The two books are very different. The first is a well-known text whose sexual interpretation is quite obvious and lends itself well to erotic interpretation, the second plays around the character of Arsène Lupin, a fictional gentleman-thief and master of disguise created in 1905 by the writer Maurice Leblanc, and not a character known to inspire erotomaniacs. Where did the ideas for these choices come from?

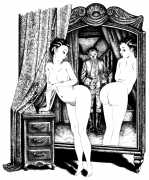

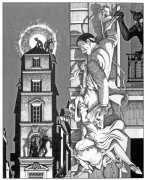

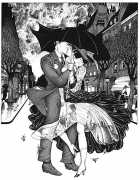

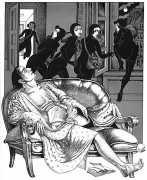

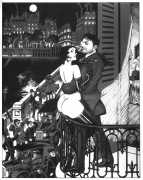

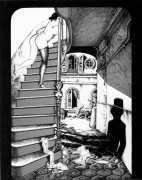

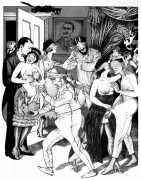

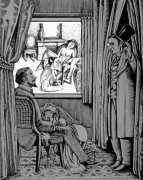

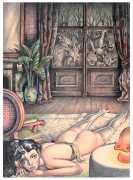

Well, the eroticism of Beauty and the Beast is obvious. In Confessions I wanted to create a fantasy Paris, nocturnal, ancient, labyrinthine, full of secret passageways leading to decadent mansions, underground alcoves, sumptuous passages and halls, all much more erotic than modern supermarkets and underground car parks.

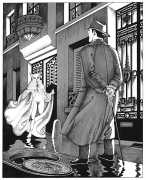

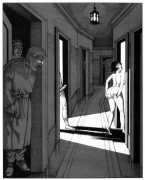

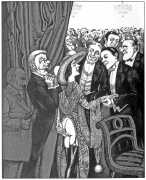

The character of Monte-en-l’air was inspired by one of these heroes of soap operas at the end of the nineteenth century that I find so attractive. I have always liked the image of the Phantom in evening dress above Paris, the original version without the hood, the posters and covers of novels with heroines like Irma Vep, and heroes in opera hat, cape and tuxedo, theatrically lit. These characters are not always very erotic; they are too busy with revenge. But I disagree with you, Arsène Lupin should inspire erotomaniacs! In each story he seduces a woman, exchanges information about difficult cases for the promise to sleep with him.

The images in the two books are frankly pornographic. There are references to sexuality and eroticism in your earlier work, but here they are tackled bluntly. Why did you wait so long?

Over the past twenty years I’ve slipped more and more naughtiness into some of my drawings, and especially into my paintings. I think it’s down to personal evolution. Desires seem to arrive when they want to, or when they can – I don’t do much deciding, I just receive, that’s all. I’ve always liked to draw funny fairyland-like people, so I worked for a long time for children. But there are different periods in our lives, times when we are ready. I can’t be more precise.

Confessions d’un monte-en-l’air seems more elaborate than Beauty and the Beast, with more detailed work, especially in the Parisian architecture. Did it just come like that or are there artistic choices behind it?

Beauty and the Beast had a fairly simple scenario: two heroes in a unique setting, a park and a castle, all in a more or less whimsical eighteenth century. Confessions takes place in a more complex world: the hero meets all sorts of different characters, in a new place each time.

I wanted the urban adventures of the monte-en-l’air to take place in compelling settings; this mysterious 1900s Paris needed twilit or stormy lighting, rain and wind, angled perspectives, old houses nested one inside the other, where the hero can flit from roof to roof, appear through hidden doors, and disappear at will. I like the details, the small things seen in the distance through a window or in a mirror.

I wonder how much your feminist work for children is compatible with such raw erotic work. It doesn’t seem inconsistent to me, but what would you say?

For me too it doesn’t seem at all incompatible, unless you are rhyming feminism with puritanism, which sometimes happens. Feminism is about the social; my erotic drawings come from a more intimate sphere, that of my imagination. When you publish your images they no longer belong to you, other people will either accept or reject them. Everyone sees what they want in an image, often things the artist had not intended or imagined, so who is to say who decides whether an image is dangerous or degrading?

I quite understand that there are many people who are not particularly interested in sexual stories and images, and it seems correct to me not to inflict them on everyone by displaying them on subway corridors. Other than that, I hope that no censorship of images will ever be imposed, that it will always be possible to represent our sexual fantasies.

As far as I’m concerned, erotic stories and sexual images have always interested me ever since I was young, and it hasn’t stopped since. I collect with great pleasure books and erotic images, ranging from Achille Deveria to Ishibun Sugimoto, Jean-Jacques Lequeu, Eugene Poitevin, Fameni, Takato Yamamoto, Martin van Maele – there are thousands.

Your illustrations show a wide range of sexual possibilities rather than concentrating on any particular practice. Does this say anything about yourself?

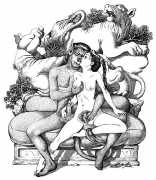

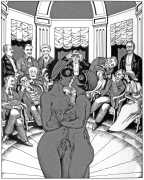

I didn’t want to make any sort of inventory of all that is practised, nor a catalogue of the various forms of sexuality. Also I didn’t want to be monotonous and reproduce the same obsession page after page, although I can appreciate this with other illustrators. I wanted to vary the pleasures a bit; certain scenes were also suggested by the author, which introduces another imagination.

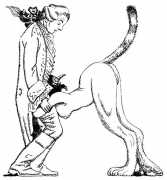

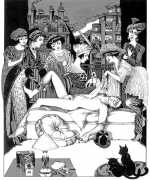

Does it say anything about me? Quite possibly! I do like introducing animals, so you might accuse me of zoophilia, but they are there as much for the comedy as to please zoophiles. I like to draw humanised animals, and vice versa, partly because we are animals, and partly because most of the time they are beautiful, though I recognise that there are creatures more attractive than the warthog that waltzes with the Belle! And is my art transgressive? I do have a bit of a reputation in my children’s books for scariness, but I don’t really understand why.

It’s usually male illustrators who produce erotic work. Do you consider yourself something of a pioneer?

Well, I’m by no means the first. For example, Suzanne Ballivet started by publishing fashion designs in the 1920s, then humour, costumes and theatre sets in the 1930s; she produced her first ‘sensual’ drawings around her fortieth birthday, but it wasn’t until until the 1950s that she produced explicitly-illustrated books such as L’initiation amoureuse.

Do you have any other erotic projects in progress?

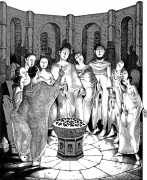

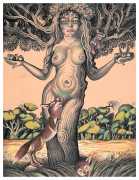

Yes, I’m preparing a third – and probably last – erotic book, which will be called something like Contes de la fève et du gland, based on fairy tales, legends and myths. The images are in colour, done with coloured pencils. It’s much more laborious than number two, which was more laborious than the first, because it deals with characters who are all different and in different settings – the sky, the ocean, cities, forests, and in different eras.

In many ways it closes the loop for me – a book which is both fairy tale and erotic. As Jean Cocteau once said, ‘Erotic stories are the fairy tales of grown-ups’.

You can read the original interview (in French) here.

Nicole Claveloux’s official website is here.