Ernst Ludwig Kirchner grew up in Aschaffenburg, a Bavarian town south-west of Frankfurt am Main. He studied at the Faculty of Architecture of the Technische Universität (Higher Technical School) in Dresden, then attended the Staatsschule für angewandte Kunst (School of Applied Arts) in Munich.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner grew up in Aschaffenburg, a Bavarian town south-west of Frankfurt am Main. He studied at the Faculty of Architecture of the Technische Universität (Higher Technical School) in Dresden, then attended the Staatsschule für angewandte Kunst (School of Applied Arts) in Munich.

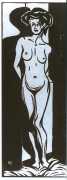

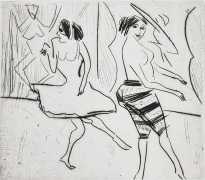

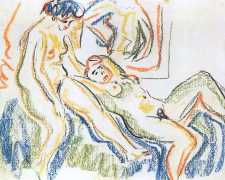

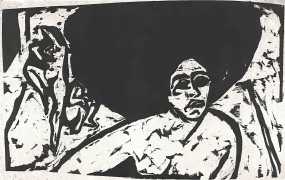

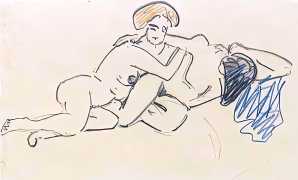

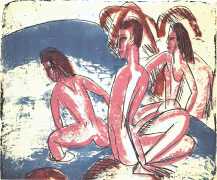

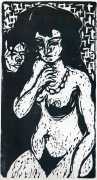

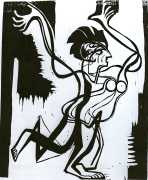

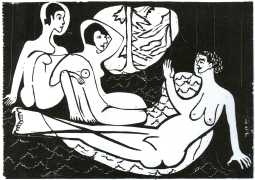

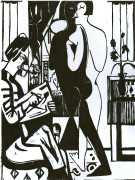

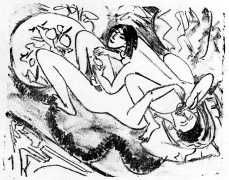

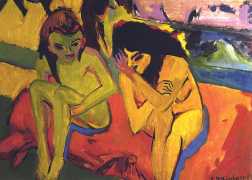

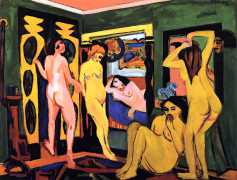

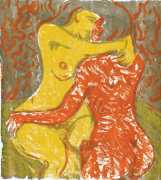

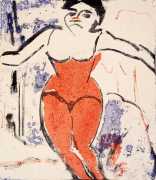

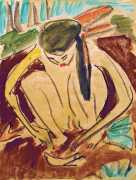

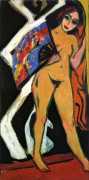

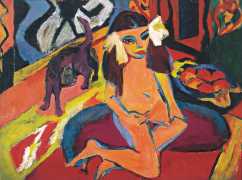

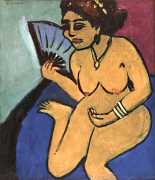

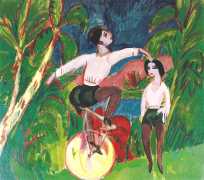

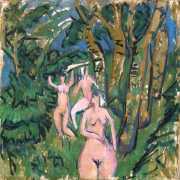

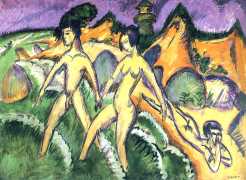

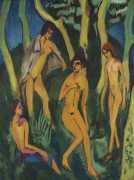

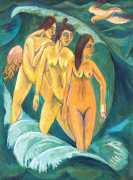

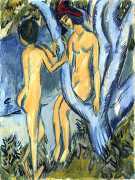

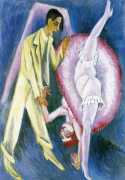

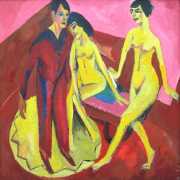

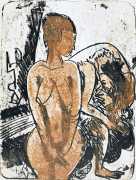

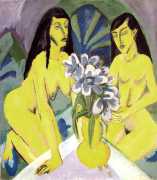

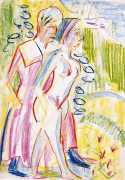

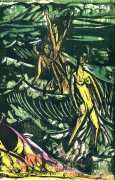

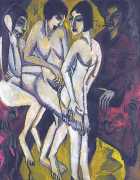

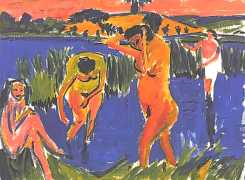

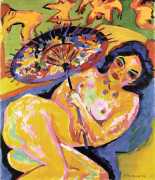

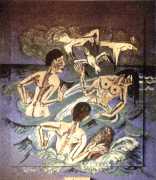

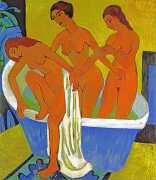

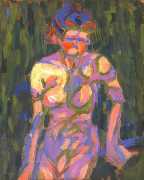

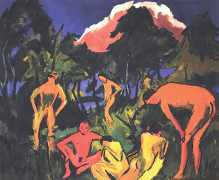

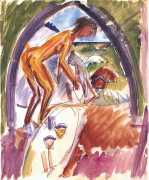

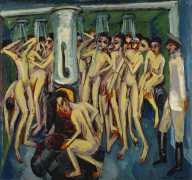

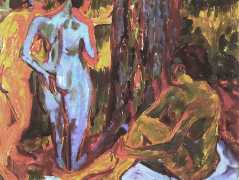

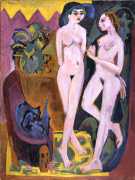

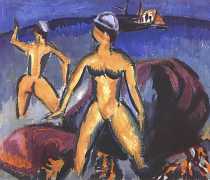

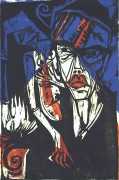

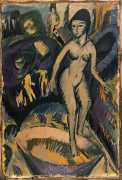

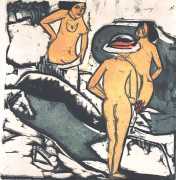

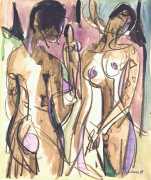

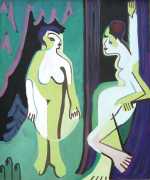

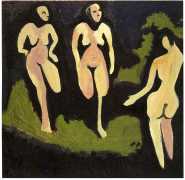

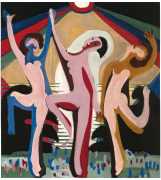

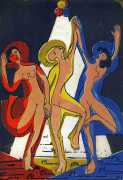

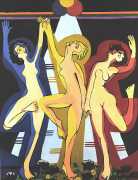

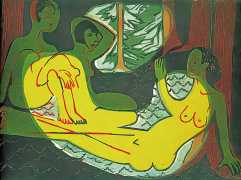

On his return to Dresden in 1905, Kirchner, along with Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff – all relatively untrained in the visual arts – founded the artists’ group Die Brücke, or The Bridge, a moment that is now considered the birth of German expressionism. Impelled, in Kirchner’s words, ‘to express themselves directly and authentically’, they rejected academic art as stultifying and searched for means to make work that possessed a sense of immediacy and spontaneity. They culled inspiration from the emotionally expressive works of Vincent van Gogh and Edvard Munch, Oceanic and African art, and German Gothic and Renaissance art, which led them to enthusiastically embrace the woodcut, a print medium through which they pioneered their signature style, characterised by simplified forms, radical flattening, and vivid non-naturalistic colours. During the existence of the group nine exhibitions took place throughout Germany. All were marked by wide public attention, but the reviews in the press were extremely negative.

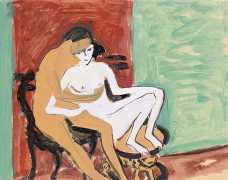

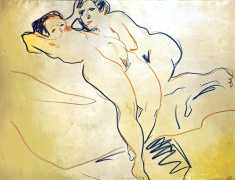

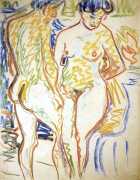

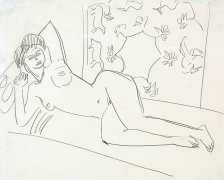

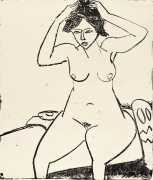

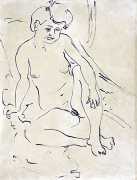

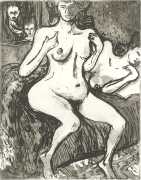

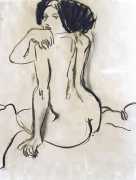

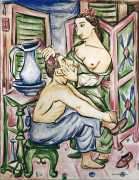

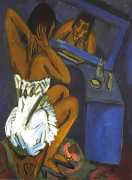

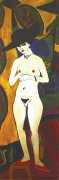

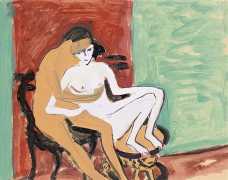

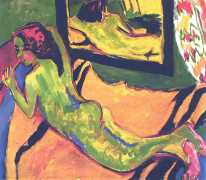

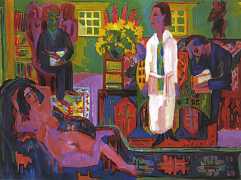

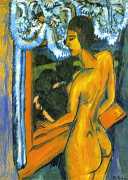

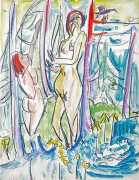

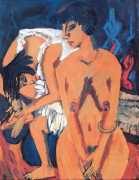

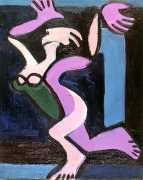

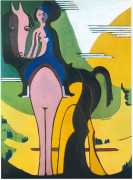

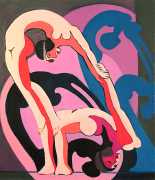

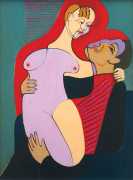

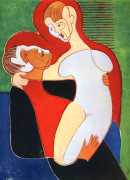

Kirchner was the first of the Brücke artists to show in practice how colour, line and plane should look in the expressionist understanding and how they tend to be reborn into each other. Pictures, in his opinion, were not just images of certain objects, but independent creatures of lines and colours that are similar to their subjects, so that the key to understanding what is being depicted is preserved. By nature, Kirchner understood everything that can be seen or felt. His work was influenced not only by acquaintance with the painting of Van Gogh and Munch, but also by studying the forms of folk primitivism.

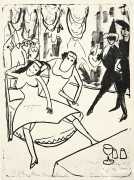

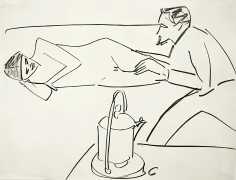

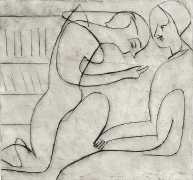

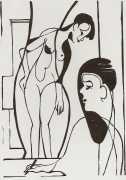

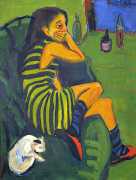

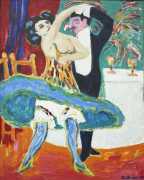

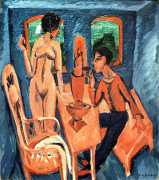

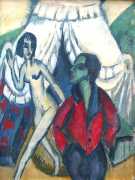

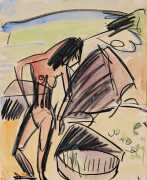

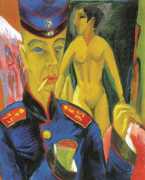

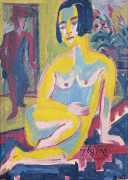

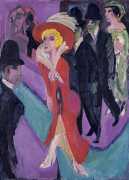

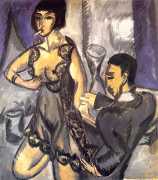

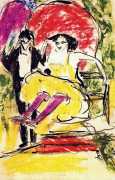

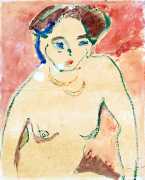

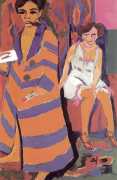

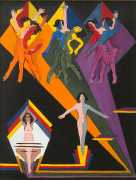

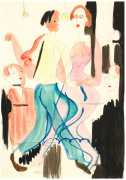

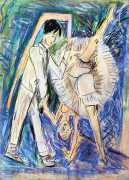

After moving to Berlin in 1911, in 1913 he published Chronik der Brücke (Manifesto of The Bridge) in an attempt to unify the thinking of the group, but soon quarrelled with the other members and went his own way. After Die Brücke disbanded, Kirchner found a subject in Berlin itself, newly established as a cosmopolitan metropolis. He captured its hectic pace and artistic freedom in dozens of quick sketches, many of which became the inspiration for new paintings and woodcuts. Kirchner was by nature restless, and when he moved to Berlin he felt that the crazy bustle of the big city was just what he needed. Elegant and artistic women, whom the artist liked to draw, seem to make contact with the viewer. Their faces are beautiful, but are often indifferent and masklike.

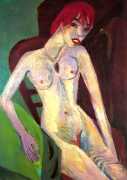

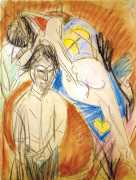

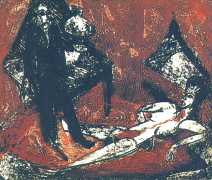

At the outbreak of World War I Kirchner volunteered for service, but he soon experienced a physical and mental breakdown and was discharged. After convalescing in sanatoriums near Davos in Switzerland, he spent the rest of his life in the area, portraying its rural scenery, mountains, and villagers in his work. He also began to experiment with abstraction, reflecting his goal for ‘the participation of present-day German art in the international modern sense of style’.

In 1933 the Nazi regime came to power in Germany, and Kirchner – a member of the Prussian Academy of Arts and by now a well-known artist – was expelled from the academy, and 639 of his works were removed from museums throughout Germany, with many being destroyed. Ranked by the Nazis among the representatives of ‘degenerate art’, he found himself in forced creative isolation, although as a resident of neutral Switzerland he was in relative safety. However, the unfolding tragic events in Germany pushed him to commit suicide.