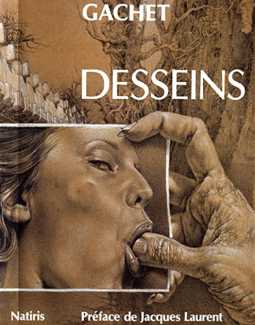

Three years after the artist’s death the Natiris publishing house produced Desseins (Designs), a collection of Gachet’s best drawings, which given how long it took him to produce each one represents the bulk of his lifetime’s output. Gachet’s friend Jacques Laurent (1919–2000), the writer and journalist, contributed a short preface.

Three years after the artist’s death the Natiris publishing house produced Desseins (Designs), a collection of Gachet’s best drawings, which given how long it took him to produce each one represents the bulk of his lifetime’s output. Gachet’s friend Jacques Laurent (1919–2000), the writer and journalist, contributed a short preface.

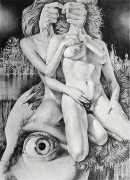

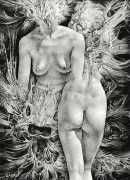

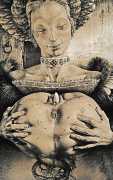

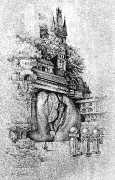

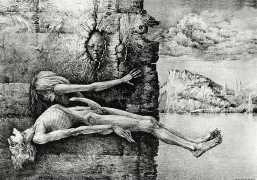

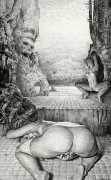

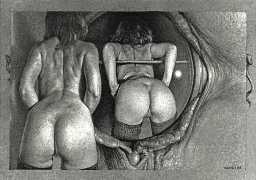

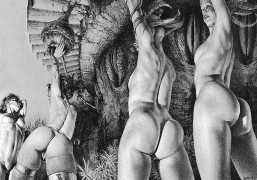

The drawings were made between 1970 and 1983, and demonstrate an artist in complete command of both technique and composition.

In the March/April 1970 issue of the French underground magazine Zoom, Eric Chapmann interviewed Gérard Gachet. The complete interview (in French) can be found here; we have translated some of the questions and answers, which provide useful insight into both the artist and his times.

How would you place yourself as an artist?

In order to simplify things let’s say within fantastic realism. That’s what I most identify with.

What does the fantastic mean to you?

The fantastic is something which is disturbing and rather dangerous.

Why drawing rather than painting?

I don’t have the temperament of a painter. I mainly work in the field of composition and texture; I have little appetite for colour.

Where have your drawings appeared?

Mostly in the Planète anthologies and in a few other magazines. I was fortunate to meet Pierre Chapelot quite by chance when he was planning the first issue of Planète, and he agreed that he would include me in the launch issue. I’ve now been working for them for three years.

You’ve exhibited as well?

About ten exhibitions in Strasbourg and two in Germany. I’ve lived in Strasbourg for twelve or thirteen years and have exhibited practically every year at least once.

Why did you choose Strasbourg?

Hard to say. I know almost all the cities in France, and I must say that Strasbourg is very attractive.

Are there any links between your art and the internationalism of Strasbourg?

I think what I’m doing is quite akin to German fantasy and romanticism. It’s also quite like the Vienna school, for example of Max Fuchs. I’m very sensitive to German romanticism, the expressionism, the morbid sensitivity, the German idea of romanticism. I’m not a city dweller. Even in Paris I know that I would be completely drowned, but I feel quite comfortable with fir trees, the Rhine, and all the rural legends.

Do you have a particular working technique?

I worked a lot with a ballpoint, but had problems because the ink tends to fade. I find ballpoint more interesting than working with a normal pen. It allows me to have worn backgrounds, surfaces which the normal pen doesn’t allow. It doesn’t allow for any degradation on the surface, which I can achieve with a ballpoint. The downside is that ballpoint ink tends to fade, but I managed to fix it with varnish and it seems to hold fairly well.

There is a certain erotic aspect of your work; how do you explain that?

I think it’s a lifestage thing. I’m thirty-five years old. There are two forms of eroticism – there is the eroticism of the eighteen-year-old boy which lasts until around twenty-four or so, then after that comes the real understanding of eroticism. This is the difference between the consumer and the gourmet. You have to become a bit of a fetishist, go through a kind of abstraction, a synthesis of desire which can be hinted at rather than shown head on. I don’t do gratuitous eroticism. I believe this is a way for me to come to explain myself in the drawings, to initiate a conversation with those who view my drawings. I’d describe my eroticism as an all-purpose eroticism rather than anything medical or anatomical. But then my eroticism is always going to be someone else’s pornography.

Tell us about your passion for reptiles

Yes, yes. At home there are seven reptiles, an aquarium, a monkey, a dog – and my wife of course. Among the animals it’s the reptiles that I prefer by far. Unlike domestic animals they’re creatures with which we cannot do anthropomorphism. With reptiles you can’t cheat, and they are absolutely magnificent animals, absolutely self-sufficient. If they bite me it’s all my fault. It provides me with the opportunity of being confronted by raw nature, not nature as we might prefer it but as it exists, with its own imperatives and its laws. I particularly love snakes – I have a grass snake, a python, a whiptail, a viper and a cobra.

When you’ve finished a drawing are you satisfied with it?

I’m satisfied while I’m doing it, and don’t stop until I’ve finished it, but then it’s not mine anymore. It’s a thing that came out of me. I look at it with a certain tenderness for a week or so, but am then very happy to let it go. I know this is often a big problem for artists; they can become very attached to their work. I think it’s useful to be able to get rid of drawings quickly; after all, I’ve done all my thinking and the solution has been arrived at. It’s resolved. It’s like a child, you have to have the courage to let it live its own life.